|

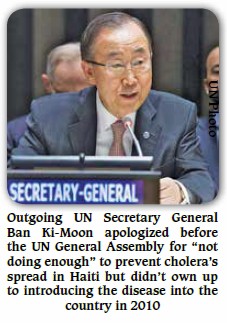

United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon, who will

step down at the end of this month, made his most

explicit apology yet for the UN’s role and

responsibility in Haiti’s cholera epidemic, the world’s

worst.

However, in his ballyhooed

Dec. 1 address to

the UN General Assembly, Ban stopped short of admitting

that UN soldiers militarily occupying Haiti since 2004

introduced the deadly bacterial disease into the country

in 2010.

“On behalf of the United Nations, I want to say

very clearly: we apologize to the Haitian people,” Ban

said in the nugget of his long speech in French,

English, and Kreyòl. “We simply did not do enough with

regard to the cholera outbreak and its spread in Haiti.

We are profoundly sorry for our role.”

UN Special Rapporteur Philip Alston, whose

scathing

report last August

put Ban on the hot seat, rightly dubbed it a

“half-apology.”

“He apologizes that the UN has not done more to

eradicate cholera, but not for causing the disease in

the first place," Alston told the

Guardian.

The epidemic began when cholera-laced sewage from

Nepalese UN soldiers’ outhouses leaked into the

headwaters of Haiti’s most important river, the

Artibonite. Within a year, it had spread throughout the

country. To date, cholera has killed about 10,000

Haitians and sickened one million.

Ban’s 11th hour “half-apology” comes

after a relentless campaign of legal suits, popular

protests, letter writing, condemnation by celebrities,

and a withering torrent of critical press reports,

books, and films.

The legal crusade began on Nov. 3, 2011 when

lawyers with the Boston-based Institute for Justice and

Democracy in Haiti (IJDH)

filed a claim within

the UN’s internal grievance system to obtain

compensation for Haiti’s cholera victims, as well as a

formal apology and the construction of modern water and

sanitation systems. They were rebuffed in February 2013,

a year and a half later, with a

two page letter

simply stating that the claims were “not receivable”

because the UN enjoys legal immunity.

For the next three years, the IJDH, along with

other legal teams, attempted to sue the UN in New York

State courts, but in 2015 and 2016 decisions, both

district and

appeals courts

upheld the UN’s legal immunity, as argued by U.S.

government attorneys. (The UN never deigned to appear.)

But as lawyer Brian Concannon, Jr., the IJDH’s

executive director, noted: “Every time they had a

victory in court supporting their supposed legal

immunity, it turned into a public relations disaster due

to the negative press coverage and its amplification by

social media.”

As Special Rapporteur Alston remarked, the UN was

employing a “stonewalling” strategy and “double

standard” which “undermines both the UN's overall

credibility and the integrity of the Office of the

Secretary-General.”

It is true that the United Nations Mission to

Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH) troops “did not do enough” to

stop cholera’s spread from the central Artibonite Valley

where it emerged. As a veteran cholera-fighting Cuban

doctor told

Haïti

Liberté when the epidemic began in

October 2010: “They

are doing exactly the wrong thing” by admitting cholera

patients into general hospitals and clinics and not

sealing off the outbreak area.

Ban’s carefully worded apology, similar to his

2014 tour of Haiti with

statements citing the UN’s “moral duty” to

fight cholera, seek to repair the UN’s tattered

credibility and Ban’s pock-marked legacy, while avoiding

any true legal liability and obligations.

"We now recognize that we had a role in this but

to go to the extent of taking full responsibility for

all is a step that would not be possible for us to

take," said Deputy Secretary-General Jan Eliasson.

To sweeten the deal, Ban promised (although he

won’t be around) that the UN would try to raise “around

$400 million over two years” to support efforts like a

cholera vaccination campaign (which Haitian

biologist/journalist Dady Chery

condemns as

“useless”) as well as “improvements in people’s access

to care and treatment when sick, while also addressing

the longer-term issues of water, sanitation, and health

systems.” This latter step is the only way to stop the

spread of cholera.

The UN’s previous anti-cholera fund drives have

been singularly unsuccessful,

raising only 18% of

a $2.1 billion “Cholera Elimination” plan from

2013-2022. As Concannon told a Dec. 2 conference call,

“as hard as we fought to get those promises made, we’re

going to have to fight even harder to get those promises

fulfilled.”

“For six years, the UN has been saying it doesn’t

have the money,” Concannon continued.

“We’ve been saying that they’ve

been spending between $800 million to $400 million a

year for over 12 years for a ‘peacekeeping mission’ in a

country which has not had a war in my lifetime... Since

the cholera epidemic started, the MINUSTAH has spent

over $4 billion, and we think that’s a powerful argument

to make when the UN says it doesn’t have money for a

cholera epidemic which they started, while they have

plenty of money for a ‘grave threat against

international peace’ which never existed.”

Indeed, it remains to be seen if the UN will use

its new cholera-fighting promises to prolong the mandate

of the highly unpopular MINUSTAH, which was originally

proposed to deploy only six months in 2004. Its latest

six-month extension expires in April 2017, before which

the mission will undergo a

“strategic assessment,”

Ban said in August.

In conjunction with his Dec. 1 address, Ban

released a

Nov. 25 report to

the General Assembly entitled “A

new approach to cholera in Haiti.” In it, he

referred to a 2013 UN-commissioned medical panel’s

report which stated that “the exact source of

introduction of cholera into Haiti will never be known

with scientific certainty,” however, “the preponderance of the evidence and

the weight of the circumstantial evidence does lead to the conclusion that

personnel associated with the Mirebalais MINUSTAH

facility were the most likely

source.” This is the closest Ban ever came to an actual

admission of guilt for an epidemic whose source “will

never be known with scientific certainty.”

“We're moving forward but we're not finished,”

said Jean-Charles August, a teacher from Petit-Goâve,

who is one of the cholera victims represented by IJDH

and its sister International Lawyers Bureau (BAI) in

Haiti. “We want eradication and compensation.”

“This is more of a beginning than an end in terms

of our fight,” Concannon told the conference call of

lawyers, activists, and journalists. In the weeks and

months ahead, the IJDH, along with the Haitian

government and others, will be in negotiations with the

UN for exactly how “eradication and compensation” should

come about. The current Haitian UN ambassador, Jean

Wesley Cazeau, applauded Ban’s “radical change of

attitude” and looked forward to concrete results.

As a Dec. 5

New York Daily News editorial summed up the

situation: “Up next, and urgently: a practical reckoning

to undo the damage done.”

In short, only time will tell if Ban’s parting gesture

reflects a genuine committment within the UN to

compensate the Haitian people and eradicate cholera, or

was simply a head-feint to continue the UN’s shameful

record, from Korea to Afghanistan to Haiti, of leaving

death and destruction in countries it invades (at

Washington’s behest) to supposedly help. |