|

Like

the plantain weed,

Plantago major,

which so reliably matched the movements of European

settlers through North America that it became known as

“the white man’s footprint,” the cholera epidemics of

the last 15 years have closely followed the growth and

trajectories of United Nations troops.

Haitians have been infected not once, but at

least twice with cholera from the UN. As of this

writing, Haiti is smarting from a resurgence of cholera

that began in September 2015. The infections are

probably not due to the Nepalese strain of cholera that

caused the October 2010 epidemic but to newly introduced

cholera from Bangladesh. Recovery from an infection with

one strain of cholera does not confer immunity against

another, so the UN has sickened some unfortunate people

and their children multiple times. Before I go into the

details of the new epidemic, let us look more broadly at

the UN peacekeepers’ role as a new vector of disease in

the world.

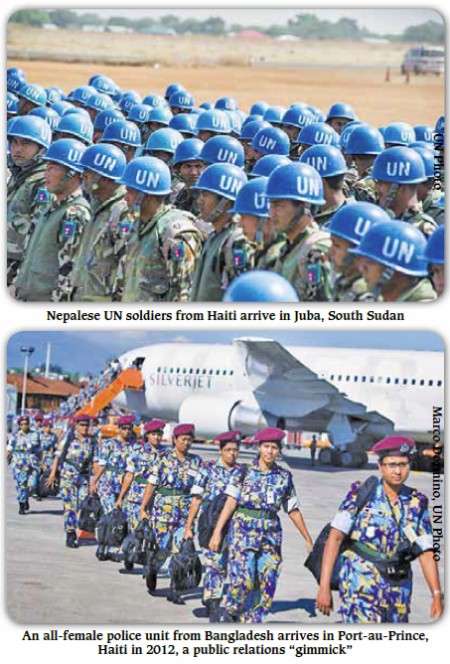

UN Deployments Worldwide

The UN currently runs 16 military

occupations, with guidance and funds from major world

powers and the so-called emerging powers. Multinational

armies of blue helmets prey on various countries,

especially in west and central Africa, mainly to

safeguard the colonial interests of France and the

United States. Emerging powers like Canada, Brazil,

India, and South Korea tag along, salivating for seats

on the UN Security Council. Their representatives enrich

themselves on the kickbacks from contracts for lucrative

projects such as

mining, peacekeeper

training, construction, hydro-power, and textiles, which

depend on the oppression of a supply of abundant

cheap labor.

Altogether, the military occupation missions cost

more than $8 billion per year. Their names are confusing

interchangeable acronyms like MINUSCA, MINUSMA,

MINUSTAH, UNMIL, and UNMISS, and it is quite appropriate

that this should be so, because, everywhere the blue

helmets go, their activities and

atrocities are the

same. These include assaults,

rapes, arms

trafficking, human trafficking, prostitution,

murder, and the

dissemination of infections. Except in Lebanon, where

the actions of Hezbollah have kept the UN troops in

check, cholera epidemics have flared up in every country

where these troops have had a major presence since 1999.

The above table suggests that, although Haiti’s

2010 cholera was the most scandalous and best-studied

case of the UN’s introduction of an epidemic of disease

into a country, it was probably not the first such

infection nor the last. The reason for these infections

is simple: the introduction of UN troops into countries

represents a heavy burden on their infrastructure. The

sanitation on UN bases is usually shoddy, and UN troops’

untreated wastes are routinely dumped into rivers.

Furthermore, the largest

contingents of UN troops

come from Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, all of which are

South Asian countries where cholera is endemic.

I have closely monitored Haiti’s epidemic and

examined the others, and it is evident that they follow

a predictable pattern. The citizens of the invaded

countries are left to live under appalling conditions,

usually near stagnant water and uncollected rubbish,

while the UN and their associated medical

non-governmental organizations (NGO) settle into the

best living spaces and incessantly predict that the

filth elsewhere will lead to a cholera epidemic for the

native population. Simultaneously, contingents of UN

troops are allowed to

take leaves in their

countries at the height of cholera epidemics, and they

are subsequently reinserted, with little medical

oversight, into the unsuspecting populations. Whether or

not this practice is deliberately intended to trigger

epidemics, it does so as surely as an injection of a

growing bacterial culture leads to an explosion of

exponential bacterial growth in a previously sterile

broth. In the end, the victims are blamed for their

supposed poor hygiene. The UN, which has caused the

infection, not only gets away with it but recasts itself

as a savior: a provider of oral cholera vaccines, which

just happen to benefit its friends in academia with

financial interests

in the vaccines. It hardly matters that the vaccines are

useless.

One Country, Multiple Infections

Recent research in Haiti has showed

that, lately, when some Haitian cholera patients excrete

the cholera bacteria in their stools, these bacteria are

accompanied by a virus (or phage) called ICP2, whose DNA

sequence closely matches that of a virus from

Bangladeshi patients. It is certain that the Bangladeshi

virus got into Haiti on Bangladeshi strains of cholera

bacteria excreted by Bangladeshi peacekeepers. According

to

Andrew Camilli and

his colleagues at Tufts University, who first sequenced

the genomes of these viruses: “these phages also travel

with V. cholerae into the human host and are shed at

appreciable amounts by infected patients, where like V.

cholerae they could be spread to others via fecal-oral

transmission.” Bacterial

hosts of the ICP2 virus

include not only Vibrio cholerae O1 but also V. cholerae

O139, which originates from Bangladesh.

This infection of Haiti with cholera from

Bangladesh is terrible news, because the strains of V.

cholera O1 and O139 from Bangladesh are notoriously

pathogenic, usually carry multiple antibiotic

resistances, and have strong epidemic and pandemic

potential. Even after the cholera epidemic brought from

Nepal in 2010, Haitians were naïve to the Bangladeshi

cholerae and only became exposed to these more harmful

bacteria, starting in 2012, when the UN began to

introduce

female Bangladeshi

peacekeepers into Haiti as a sort of gimmick.

According to the American researchers, a cocktail

of three

Bangladeshi cholera viruses

(ICP1, ICP2, and ICP3) protects baby mice from becoming

ill after they are deliberately infected with cholera.

The researchers suggest that this viral cocktail might

prevent infections in the human relatives of cholera

patients. On the other hand it might not, and instead

make them very sick or even kill them. After all, humans

aren’t the same as baby mice. In any case, such research

that might potentially harm apparently healthy people

would be highly unethical. Who will prevent it from

being done on Haitians? Surely not the “Haitian National

Ethics Committee” that has so far approved the work of

the U.S. researchers. And who will expel the UN once and

for all and put an end to the continued infection of

Haitians with new strains of cholera?

The World Health Organization (WHO), which is

part of the UN, reported in 2015 that there are 1.4 to

4.3 million cases of cholera and 28,000 to 142,000

deaths yearly due to cholera infections. These numbers

will surely continue to climb,

proportionately with

the “peacekeeping” budgets. The WHO offers as its main

solution the stockpiling of a large number of doses of

oral cholera vaccines. Suppose for a moment that such

vaccines should work — which they do not. Would the UN

then advocate universal cholera vaccination for the

world’s poor so that they might safely drink water that

has been fecally contaminated by their invaders? The UN

has never been the highly

ethical organization

it was envisioned to become, but its enthusiastic

advocacy of oral cholera vaccines does represent a new

low.

Dady

Chery is a Haitian-born biology professor at a U.S.

university. An earlier version of this article, under a

different title, was

originally published on her blog in January.

|