Préval’s suspicions about “outsiders” seeking his “success” turned

out to be justified. In two rounds of

presidential and legislative elections

held in November and March, Washington

aggressively intervened, pushing

out of the presidential run-off Jude

Célestin, the candidate of Préval’s party

Inite (Unity), to replace him with Martelly,

a neo-Duvalierist konpa singer who vocally supported the 1991 and

2004 coups d’état against former president

Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

Now the U.S. has even challenged

the legislative races which

would have given Inite virtual control

of the Parliament, and hence approval

of the President-designated Prime Minister,

Haiti’s most powerful executive

post. With U.S. support, challenges

were brought against Inite victories in

17 Deputy and two Senate races. The

Provisional Electoral Council (CEP)

ruled in favor of only 15 challenges,

leaving four seats with the original

Inite winners. The U.S. is not even letting

this mild, partial impertinence go,

yanking the U.S. travel visas of six of

the CEP’s eight members.

How did Haiti’s “indispensable

man” become so dispensable? Why has

Washington so brazenly intervened in

Haiti’s elections to limit the power of

Préval’s party and oust Inite’s presidential

candidate from the run-off?

Clues to the answer lie in secret

U.S. Embassy cables which the transparency-

advocacy group WikiLeaks

has provided to Haïti Liberté. The

cables reveal that the U.S. was primarily

irked by Préval’s dealings with

Cuba and Venezuela, where the former

Haitian president was unable “to resist

displaying some show of independence

or contrariness in dealing with [Venezuelan

president Hugo] Chavez,” as Sanderson griped in a

2007 cable.

U.S. dismay began when Préval

signed – the very day of his inauguration

– a deal to join Venezuela’s PetroCaribe

alliance, under which Haiti

would buy oil paying only 60% to Venezuela

up front with the remainder payable

over 25 years at 1% interest. The

leaked U.S. Embassy cables provide a

fascinating look at how Washington

sought to discourage, scuttle, and sabotage

the PetroCaribe deal despite its unquestionable

benefits, under which the

Haitian government “ would save USD

100 million per year from the delayed

payments,” as the Embassy itself recognized

in a 2006 cable.

A review of PetroCaribe’s genesis

and the Embassy’s response to it

provides a window into understanding

why the U.S. has been so forceful in

backing the U.S.-centric Martelly team

over Préval’s two-timing sector.

Venezuelan Trial Balloon Shot Down

Venezuelan Trial Balloon Shot Down

Venezuela first offered a PetroCaribe deal to Haiti under the de facto

government of Prime Minister Gérard

Latortue, whom Washington installed

in March 2004 after the Feb. 29 coup

against Aristide. “The government of

Venezuela planned to send a negotiating

team to Haiti (exact time undetermined)

to negotiate a deal to sell oil

at a preferential rate via PetroCaribe,”

Embassy Chargé d’affaires Timothy

Carney (the Charge) reported in an Oct.

19, 2005 cable. “Upon returning from

a recent trip to Venezuela, Minister of

Culture and Communication, Magali

Comeau Denis told the Charge she was

bringing Venezuelan oil back to Haiti

with her.”

Prior to that trip, Carney “and

Econ Counselor [his economic counselor]

had spoken to acting Prime

Minister Henri Bazin who said that the

Interim Government of Haiti [IGOH]

was looking for concessional terms for

oil purchases from Mexico and Nigeria

--but not Venezuela, he was quick to

emphasize,” Carney continued. “In a follow-up conversation, Charge reiterated

the negatives of such a deal with

Venezuela. Bazin listened and understood

the message,” that Washington

would be unhappy about any oil deal

with Venezuela.

To drive the point home, “Econ Counselor met with a contact at the

Finance Ministry October 13 who confirmed

that the IGOH has no plans to

participate in any PetroCaribe deal,”

Carney explained. “He added that our

message to Bazin had an impact: Bazin

had seen a draft of comments to

be made by Haiti’s representative

to the IMF [International Monetary

Fund] that included a vague reference

to someday purchasing oil at concessional

prices from Venezuela, and Bazin

had the sentence deleted, the only

change he made on the text.” This was the kind of ultra-servile response

Washington expected from a puppet regime

in Haiti.

But Carney understood that Venezuela

had not really expected to strike

a deal with Latortue’s de facto government.

“We suspect that the recent efforts

by Venezuela here are designed

more to get the issue on the agenda,

and that Chavez’s strongest efforts will

come after the elections, when a new

Haitian government is inaugurated in

February 2006,” Carney concluded.

In a Nov. 7, 2005 cable, Carney

noted that “the pressure is still on the

IGOH to strike a deal with Venezuela”

as “organizations that have organized

demonstrations in the past against

high prices in Haiti have publicly

called on the IGOH to accept Venezuela’s

offer to negotiate on a concessional

deal.” However Bazin reassured

the Embassy that “Haiti was far

from any agreement with Venezuela”

and “instead discussions were ongoing

with the Government of Mexico

to obtain a special deal from them on

petroleum imports.” (Dominican Foreign

Minister Morales Troncoso told

the DR’s U.S. Ambassador and visiting

Western Hemisphere Affairs Deputy

Assistant Secretary Patrick Duddy that “President Fox of Mexico was proposing

a ‘Plan Puebla Panama’ to counter

Chavez’s ‘Petrocaribe’,” reported a Jan.

23, 2006 cable from the Santo Domingo

Embassy.)

As Préval Comes In, Troubles Emerge

Haiti’s presidential election did

not take place until Feb. 7, 2006, and

it was won by René Préval. Even before

his May 14, 2006 inauguration,

Préval clearly was anxious to allay

Washington’s worries that he might

lean towards its South American challengers.

“He wants to bury once and

for all the suspicion in Haiti that the

United States is wary of him,” Ambassador

Sanderson, then newly appointed,

reported in a Mar. 26, 2006 cable.

“He is seeking to enhance his status

domestically and internationally with

a successful visit to the United States.”

This was so important that

“Préval has

declined invitations to visit France,

Cuba, and Venezuela in order to visit

Washington first,” Sanderson approvingly

noted.

The new Haitian president went

to great lengths to dispel the notion

that he had any political sympathies

for Latin America’s socialist regimes.

“Préval has close personal ties to

Cuba, having received prostate cancer

treatment there, but has stressed to

the Embassy that he will manage relations

with Cuba and Venezuela solely

for the benefit of the Haitian people,

and not based on any ideological affinity

toward those governments.”

But in April, shortly after his

Washington visit, Préval traveled to

Havana; the result confirmed Washington’s

fears. “President-elect Préval

announced to the press April 18 that

Haiti will soon join Venezuelan President

Hugo Chavez’s energy initiative,

PetroCaribe,” Sanderson reported in an

April 19, 2006 cable. “Préval made the

announcement after returning from a

five-day trip to Cuba, where he discussed

the subject of Petrocaribe with

the Venezuelan Ambassador to Cuba.”

But Sanderson made clear that the Embassy

– her Post – would not give up

without a fight.

“Post will continue to pressure

Préval against joining PetroCaribe,”

she wrote. “Ambassador will see

Préval’s senior advisor Bob Manuel today.

In previous meetings, he has acknowledged

our concerns and is aware

that a deal with Chavez would cause

problems with us.”

In a cable nine days later, Sanderson

recognized that Préval was under

“increasing pressure to produce immediate

and tangible changes in Haiti’s

desperate situation.” She also noted

that

“Préval has privately expressed

some disdain toward Chavez with Emboffs

[Embassy officials], and delayed

accepting Chavez’ offer to visit Venezuela

until after he had visited Washington

and several other key Haitian

partners. Nevertheless, the chance to

score political points [with the Haitian

people] and generate revenue he can

control himself proved too good an opportunity

to miss.”

Embassy cables always flag “independence”

as this one decried Préval’s

being able to “generate revenue he can

control himself .” Sanderson went on

to warn that Préval could “redirect the

40% that would have been spent on

fuel to ‘special presidential’ development

projects” and “we are wary of

the creation of a special presidential

fund.... We will encourage Préval to

channel the money through existing

programs,” meaning those which the

State Department’s U.S. Agency for International

Development (USAID) had

funded and therefore controlled.

In April 2006 cable, we see

Sanderson hint at an observation that

she would make almost a year later,

that “Préval and company may be

overselling their irritation toward

Chavez for our benefit, but Préval has

consistently voiced wariness of Chavez

in conversations with Emboffs going

back to the early stages of the presidential

campaign in 2005.”

On the surface, Préval feigned

ignorance of the hemispheric conflict

between the U.S. and Venezuela. “One journalist asked Préval when he returned

from Caracas if there would be

‘consequences’ for Haiti building links

with Venezuela, which Washington increasingly

sees as a regional threat,”

wrote the weekly Haïti Progrés in May

2006. “‘The problems between the

United States and Venezuela are problems

that those two countries have to

resolve themselves,’ Préval responded.

‘It does not affect Haiti in any way.’”

This was obviously untrue. In a

May 15, 2006 cable reviewing the now inaugurated

president, Sanderson noted

that “despite U.S. discomfort with his

links to Cuba and Venezuela, Préval

seems determined to mine those relationships

for what he can obtain.” This

“pragmatism,” as she called it, would become the nub of U.S. dissatisfaction with Préval.

Big Oil Fights PetroCaribe in Haiti

On May 14, 2006, immediately

after his inauguration, Préval summoned

the press to a room in the Palace

where he ostensibly signed the Petro-Caribe agreement with Venezuelan Vice

President Jose Vincente Rangel (“Apparently,

the signing... at the inauguration

on May 14 was ceremonial... and the

first shipment was a grant, not a part

of the loan agreement,” Sanderson

wrote later in an August cable.)

But it would be almost two years

before PetroCaribe oil would begin

flowing into Haiti, due to a myriad of

political and logistical obstacles.

The first hurdle was that Venezuela

needed to give the petroleum to

a state-owned oil company, which Haiti

doesn’t have. So it was proposed that the

oil be given to Electricité d’Haïti (EDH),

the state-owned power company.

Michel Guerrier, the director of

Haiti’s only domestic oil distribution

company, Dinasa or National (which

is owned by Haiti’s richest man, Gilbert

Bigio), told the Embassy’s Economic

Officer “one possibility is that PetroCaribe

will sell the oil to Haiti’s National

Electricity Company ... which will then

sell to the four oil companies operating

in Haiti: Texaco, Esso (a.k.a.

Exxon), National (formally Shell),

and [French-owned] Total,” explains a

May 12, 2006 cable. Guerrier also said

that PetroCaribe “is a great deal for

the Haitian government” and “speculated

that the government, in order to

retain total control over the supply of

the oil market (they already control

the price), may put an end to the non-

PetroCaribe oil-bearing ship which arrives

every three weeks.”

Sanderson predictably opposed to

the idea, calling EDH “an inefficient and

corrupt public entity” while recognizing

that “filtering oil through EDH could

ensure enough fuel to power the electricity

plants, without relying on the oil

companies as a costly back-up plan.”

Not surprisingly, all three foreign

oil companies also opposed the Haitian

government’s plan. Sanderson reported

in a May 17, 2006 cable that “Dinasa,

which supplies to Haiti’s domestic oil

company, National, is the only voice

in the oil business to endorse Préval’s

proposal to have EDH control the oil

supply. The other international oil

companies are increasingly concerned

-- both Texaco and Esso will meet with

the Ambassador in the near future

-- that they will have to buy their oil

from the GOH [Government of Haiti].”

On behalf of the oil companies and

against the obvious benefits for Haiti,

Sanderson said “we will continue to

raise our concerns about the Petro-

Caribe deal with the highest levels of

government...”

In a June 1 cable, Sanderson

reported that “Haitians have noted...

that electricity in Port-au-Prince has

improved since Préval’s inauguration

with 6 to 8 hours a day, usually late

at night until morning in residential

areas,” but the Embassy continued to

oppose the Venezuelan oil delivery.

In a July 7 cable, she said that

Dinasa President Edouard Baussan told

her that “the three international oil

companies in Haiti feel uninformed

about Haiti’s PetroCaribe plan and

are wary of how PetroCaribe will affect

their operations.” Baussan did

not know that “separately, the Ambassador

met with representatives of

ExxonMobil and Texaco [owned by

Chevron],” as Sanderson explained to

Washington. “Both companies were

concerned and curious about how

Préval planned to implement Petro-Caribe.” Sanderson finished with some

wishful thinking: “PetroCaribe seems

stalled indefinitely, and it is possible

that Haiti will not move forward with

the agreement. The first and so far

only ship, which was a minor victory

for Venezuela’s Caribbean campaign

and a tangible sign from Préval to his

constituents that he will bring change,

may mark both the beginning and the

end of PetroCaribe in Haiti.”

Venezuelan Oil Starts to Flow

However, it was not to be the

end, as the Embassy was to quickly

learn. Three weeks later, on July 28,

Sanderson had to write that “the Petro-Caribe petroleum ... has finally hit

the local market. The Haitian Government (GOH) is selling the

entire shipment, including the diesel (initially intended as a

donation to the national electricity company) and the gasoline,

at the same price as petroleum from a July 14 [oil] industry

ship. (Note: The industry shipment arrives about every two to

three weeks. Due to regular arrivals, petroleum companies have

not experienced fuel shortages in several months. End note.) So

far Dinasa, Haiti's domestic petroleum company, and Total, the

French petroleum company with which the GOH has close relations,

have expressed an interest in purchasing the PetroCaribe

petroleum from the GOH. The two U.S. companies, Esso (ExxonMobil)

and Texaco (Chevron), have received the proposal but have not

responded."

Three days later, Sanderson added an SBU: Sensitive but

Unclassified Information. "The GOH continues to misconstrue

the actual benefits of the PetroCaribe deal," she

condescendingly complained. "Ambassador has personally

addressed the issue of PetroCaribe with GOH officials at the

highest level explaining the pitfalls of the agreement... they

do not have a state-owned oil company; they lack adequate port

and storage facilities, necessitating use of private storage;

and poorly-maintained roads and theft make transportation from

the port to the final destination point difficult. Post has also

reminded GOH officials that the transportation of PetroCaribe

petroleum is not insured by Venezuela, and is often transported

in ships which do not meet international standards." But,

with her usual desire to highlight Préval’s amenability, she

concluded that "finally, the GOH has stated that the

international oil companies operating in Haiti are vital to the

economy and does not want to risk pushing them out of the local

market."

One month later, on August 25, 2006, Embassy Chargé

d'Affaires Thomas C. Tighe wrote a cable that the Haitian

Parliament was studying and likely to ratify the PetroCaribe

agreement "because of the seemingly huge benefit to Haiti"

and "PetroCaribe provides easy access to extra cash." In

the same cable, he provides an SBU that "Public Works

Minister Frantz Verella confirmed the arrival of a Venezuelan

shipment of 10,000 barrels of asphalt. The GOH is having the

same problems with the asphalt that they had with first shipment

of petroleum: they are not sure how to transport the asphalt to

its final destination and have no place for its storage."

Haiti, which has some of the world’s worst roads, ended up

selling the asphalt to the Dominican Republic, according to a

May 24, 2007 cable.

PetroCaribe Ratified Unanimously

In an August 30, 2006 cable, Tighe reported that "Parliament

ratified the PetroCaribe agreement during a session of the

national assembly [Aug. 29], which included 19 of 27 senators

and 47 of 88 deputies. 53 voted in favor and 13 abstained; no

parliamentarians voted against ratification." He also noted

that "because Haiti has a relatively low petroleum demand --

around 11,000 barrels per day -- and PetroCaribe has offered to

supply up to 6000 barrels per day, the agreement could have a

considerable effect on the petroleum industry in Haiti."

After ratification, "the international oil companies were

shocked" when "President René Préval and finance minister

Daniel Dorsainvil informed the four oil companies operating in Haiti of intentions to meet 100% of Haiti's petroleum

demand through its Petrocaribe agreement," we learn in an

Oct. 4, 2006 cable. "They thought they would still have the

right to import their own oil, with PetroCaribe supplying only

part of Haiti's petroleum demand," Sanderson explained, and

only Dinasa "was not surprised."

Christian Porter, ExxonMobil’s country manager, "speaking

for both ExxonMobil and Chevron, stressed that they would not be

willing to do this because they would lose their off-shore margins and because of Petrocaribe's unreliable reputation"

for timely deliveries, Sanderson wrote. She concluded that it

was a "dubious proposal that neither the U.S. oil companies

in Haiti -- responsible for about 45 percent of Haiti's

petroleum imports -- nor Venezuela, for that matter, is likely

to agree to."

She was wrong about Venezuela, but right about the oil

companies. An October 13 cable explains that ExxonMobil and

Texaco/Chevron were "shocked " but hadn’t "informed

the government of their concerns," to which Sanderson "encouraged

the two companies to do so."

Sanderson reiterated that despite her "numerous attempts

to discuss (and discourage) GOH intentions to move forward with the Petrocaribe

agreement, the GOH insists the agreement, implemented in full,

will result in a net gain for Haiti."

The U.S. Ambassador also detailed how the oil companies, with

her encouragement, were sabotaging the agreement: "Following

Préval's September 27 meeting with all four oil companies... the

oil industry association (Association des Professionals du

Pétrole -- APP) received an invitation to meet with

representatives of the Venezuelan oil company who were in Haiti.

All four companies refused to attend. Also, the companies

received letters separately requesting information on

importation and distribution from the GOH on October 9. So far,

no one has responded."

The oil companies also complained "that a Cuban transport

company, Transalba, will ship the petroleum from Venezuela to Haiti, and that as U.S.

companies, they would not be allowed to work directly with the

Cuban vessel."

Sanderson concluded the long October 13 cable by reminding

that she had stressed "the larger negative message that [the

PetroCaribe deal] would send to the international community

[i.e. Washington and its allies] at a time when the GOH is

trying to increase foreign investment" lamenting that "President

Préval and his inner circle are seduced by [PetroCaribe’s]

payment plan."

The Oil Companies and U.S. Embassy Dig In

With ratification and a state enterprise to receive the oil,

Préval thought he now had everything in place to get PetroCaribe

implemented in early 2007. But the oil companies still had ways

to undermine the deal.

Préval appointed Michael Lecorps to head the government’s

Monetization Office for Aid and Development Programs (formally

known as the PL-480 office), which would handle PetroCaribe

matters rather than EDH. Lecorps told the oil companies that

they would have to purchase PetroCaribe oil from the Haitian

government, but the U.S. companies said no. Quickly, there was a

stand-off.

Lecorps, "apparently infuriated by Chevron's lack of

cooperation with the GoH, stressed that Petrocaribe is no longer

negotiable," Tighe reports in a Jan. 18, 2007 cable. He also

learned that "ExxonMobil has made it clear that it will not

cooperate with the current GoH proposal either."

"Chevron country manager Patryck Peru Dumesnil confirmed

his company's anti-Petrocaribe position and said that ExxonMobil,

the only other U.S. oil company operating in Haiti, has told the

GoH that it will not import Petrocaribe products." Lecorps

told the Embassy Political Officer that Chevron "refused to

move forward with the discussions because ‘their

representatives would rather import their own petroleum products.’"

Tighe continued that "Lecorps was enraged that ‘an oil

company which controls only 30% of Haiti's petroleum products’

would have the audacity to try and elude an agreement that would

benefit the Haitian population. Ultimately Lecorps defended his

position with the argument that the companies should want what

is best for their local consumer, and be willing to make

concessions to the GoH to this end. Lecorps stressed that the

GoH would not be held hostage to ‘capitalist attitudes’ toward

Petrocaribe and that if the GoH could not find a compromise with

certain oil companies, the companies may have to leave Haiti."

Needless to say, the Embassy took a dim view of Lecorps’

attitude.

Tighe reported that "according to Dumesnil, ExxonMobil and

Chevron have told the GoH that neither company can work within

the GoH's proposed framework to import 100% of petroleum

products via Petrocaribe" and that "together, ExxonMobil

and Chevron supply 49% of all oil products in Haiti." He

explained that "the U.S. companies stand together in

opposition to the current proposal" while the French concern

"Total is discussing the agreement but has not promised

cooperation; and the only local company, Dinasa, has pledged

cooperation."

Tighe noted that Lecorps and other Haitian officials "focused

primarily on the cost benefits (estimated to be USD 100 million per year) to the

GoH, which would be used for social projects like schools and

hospitals" and that in discussing the U.S. oil companies’

intransigence, "Lecorps' self-control wavered."

Enter Hugo Chavez

In a Feb. 7, 2007 cable, Ambassador Sanderson reports that

the Embassy learned from the Haitian media on Feb. 2 "that

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez planned to visit Haiti as early

as the following week." She recalled that in March, 2006,

prior to his inauguration, "President Préval told visiting

[Western Hemisphere Affairs Assistant Secretary of State] WHA

A/S Shannon that Chavez was pushing a visit to commemorate the

bicentennial of Venezuelan flag day on March 12 in Jacmel"

but that "Préval told A/S Shannon he would do his best to

avoid Chavez, and the visit did not occur. Since Préval's

inauguration, however, Haitian-Venezuelan relations have warmed

considerably... Haitian officials report that Chavez continues

to aggressively court Haiti."

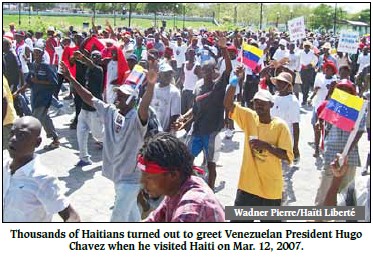

Indeed, Hugo Chavez arrived in Haiti on Mar. 12, 2007 to an

unorganized, spontaneous hero’s welcome by tens of thousands of

Haitians, who jogged alongside his motorcade to the Palace from

the airport. And the Venezuelan president came bearing many

gifts.

First, Chavez pledged a $20 million grant, which he had

announced in Venezuela a week earlier. "Reportedly, the money

will serve as humanitarian reserve fund for Haiti in order to

back social, infrastructure and power-supply programs,"

Sanderson noted in a Mar. 13 cable.

Next, Venezuelan Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Rodolfo

Sanz had in January "announced a Venezuelan donation of five

garbage trucks and one tanker as part of ‘operation pure air for

Haiti,’ which he attributed to Chavez' earlier remarks to GoH

officials that Venezuela owed a ‘historic debt to Haiti,’"Sanderson

had noted in a February cable. Chavez "re-announced his

donations of garbage trucks to Haiti," Sanderson’s Mar. 13

cable reported.

Thirdly, "the Venezuela president said he would augment

the amount of fuel Haiti will receive through PetroCaribe from

5,000 barrels [in reality, 6,000] a day to 14,000 barrels,"

Sanderson continued, surpassing Haiti’s daily fuel consumption

of 11,000 barrels.

Finally, the icing on the cake: "Venezuela pledged funds

for improvement to provincial

Haitian airports and airport runways (also previously

announced) and experts on economic planning to help identify

development priorities. Other pledges include Cuban commitment

to bring medical coverage to all Haitian communes, Cuban and

Venezuelan electrical experts to improve energy generation, and

a trilateral cooperation bureau in Port-au-Prince,"

Sanderson wrote.

Somehow, Sanderson had to give all this good news a negative

spin. She did so with her SBU "Comment" at the cable’s end: "[Former

long-time USAID employee and now presidential economic counselor]

Gabriel Verret, one of Préval's closest advisors, told the

Ambassador that the trip could have been worse. The GoH stopped

a rally that was supposed to take place in favor of Chavez and

tried to limit Chavez' speaking time at the press conference.

While waiting at the airport, Verret had let the Ambassador know

that he (and presumably the President) were frustrated with

Chavez' late arrival. Overall, disorganization and last-minute

planning were evident, and even the pledges of aid and

assistance are either old news or vague. GoH officials have

complained to post privately in the past that Venezuelan aid can

be a burden [on] the GoH..."

But Sanderson’s real vitriol would come in her next cable on

Mar. 16. She was beginning to suspect (and imply) that the

Haitians were feeding her Embassy negative reports about Chavez

disingenuously, but she wanted Washington to be the final judge.

"To hear President Rene Préval tell it, Venezuelan President

Hugo Chavez' visit to Haiti on March 12 was a logistical

nightmare and an annoyance to the GoH," Sanderson begins the

"Summary" of that cable. "Préval told Ambassador and others

that he is skeptical of Chavez's promises, especially on

delivery of gasoline through the Petrocaribe agreement.

Secretary General of the Presidency Fritz Longchamps told

Polcouns that the GoH viewed the Chavez visit as the price to

pay for whatever assistance Venezuela provides to Haiti."

Sanderson highlighted the Haitian government’s negative

feedback. "Préval told Ambassador the evening of March 13

that Chavez was a difficult guest" and "did not have a

GOH invitation but insisted on coming to mark Venezuelan flag

day." Préval then did his best to smooth Sanderson’s ruffled

feathers. "Responding to Ambassador's observation that giving

Chavez a platform to spout anti-American slogans here was hard

to explain given our close relationship and support of Haiti and

of Préval's government in particular, Préval stressed that he

had worked hard to stop much of Chavez' proposed grandstanding,"

Sanderson wrote. "He vetoed a Chavez-led procession/demonstration

from the airport to the Venezuelan Embassy (substituting a

wreath laying at Port-au-Prince's monument to Bolivar) and

limited the length of the press conference. Chavez, for his

part, insisted that the press conference proceed as scheduled,

thus cutting into bilateral meeting time. Préval added that he,

Préval, is ‘just an independent petit bourgeoisie’ and doesn't

go for the grand gestures that Chavez favors. Haiti needs aid

from all its friends, Préval added, and he is sure that the US

understands his difficult position."

Préval then addressed the massive show of support Chavez

received. "He refused to get out of the car when Chavez

insisted on greeting his demonstrators in the street on his way

in from the airport," Sanderson relayed. "Préval and

others in the government believe that the Venezuelan Charge

d'Affaires orchestrated and paid for the demonstrations by Fanmi

Lavalas militants at the airport, the Venezuelan Embassy, and

the Palace, which numbered roughly 1,000 and also called for the

return of former President Aristide." (This absurd account,

whether concocted for Washington’s benefit or not, is scoffed at

by several popular organization leaders who joined with

thousands in the rapidly organized and largely spontaneous

unpaid outpouring that day, similar to the human flood which

greeted Aristide’s return to Haiti on Mar. 18, 2011.)

But despite the complaints of Haitian officials, Sanderson

speculates that "Préval and company may be overselling their

irritation toward Chavez for our benefit... It is clear

that the visit has left a bad taste in our interlocutors' mouths

and they are now into damage control."

So Sanderson felt compelled to read the Haitians the riot act.

"The Ambassador and Polcouns have voiced concern to senior

officials that Chavez had used his visit as a platform for an

attack on Haiti's closest and steadiest bilateral ally, most

recently with [Prime Minister Jacques Edouard] Alexis yesterday,"

she wrote, ending characteristically on a rationalizing note: "At

no time has Préval given any indication that he is interested in

associating Haiti with Chavez's broader ‘revolutionary agenda’"

but "it is neither in his character -- nor in his calculation -- to repudiate Chavez, even as the Venezuelan

abuses his hospitality at home."

Préval Continues to Play "Oblivious"...

Despite his hand-wringing and Sanderson’s scoldings, Préval

kept angering the Americans. On April 26, 2007, Longchamps told

the Embassy’s Political Counselor that "Préval will attend

the ALBA [Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas] summit in

Venezuela as a ‘special observer’ for the express purpose of

finalizing a tri-lateral assistance agreement between Haiti,

Venezuela, and Cuba, whereby Venezuela will finance the presence

of Cuban doctors and other technicians in rural Haiti,"

wrote Sanderson in a cable the same day. "Longchamps

expressed surprise that the USG [U.S. Government] would take

issue with Préval's attendance at this meeting." Longchamps

reminded the Polcouns "how President Préval had curtailed

Chavez' activities during the visit and how uncomfortable

Chavez' behavior had made everyone during his stay."

Unimpressed, "Polcouns replied that though that may have been

the case, for the USG, the net result was that President Préval

gave Chavez another platform from which to attack the United

States and then saw him off from the airport," and that

Washington "did not understand why he continued to

participate in fora where Chavez vilified Haiti's most important

and reliable bi-lateral partner. USG officials would ask

President Préval this question during his upcoming trip to

Washington in May."

Sanderson said the meeting was "specifically to raise our

displeasure with Préval's Venezuela trip" and that "Longchamps’

reaction probably reflects Préval's own obliviousness to the

impact and consequences his accommodation of Chavez has on

relations with us." Longchamps "betrayed a common trait

among Haitian officials in misjudging the relative importance

that U.S. policy makers attach to Haiti versus Venezuela and

Chavez' regional impact." Sanderson suggested the U.S. "convey

our discontent with Préval's actions at the highest possible

level when he next visits Washington."

...While Getting More Aid from Venezuela

Préval returned from Caracas with "Chavez' promises to

provide a combined total of 160 megawatts of electricity" to

Haiti, after "parading with Chavez' rogues gallery of ALBA leaders," Sanderson fumes in a May 4, 2007 cable.

She outlined the essence of the Venezuelan/Cuban aid package:

"The Cubans will replace two million light bulbs throughout

Port-au-Prince with low-energy bulbs. The initiative will cost USD four million, but save the country 60 megawatts of

electricity, which costs the country USD 70 million annually.

Venezuela promised to repair the power plant in Carrefour,

generating an additional 40 megawatts of electricity.

Additionally, Venezuela will by December of this year build new

power plants across the country to add 30 megawatts to

Port-au-Prince's electrical grid and 15 additional megawatts

each for Gonaïves and Cap-Haitian, all of which will use heavy

Venezuelan fuel oil, a more efficient and less-expensive

alternative to diesel." Venezuela did carry through on all

these "extravagant promises and commitments," as

Sanderson called them. Chavez also "promised to build a

petrochemical complex, a natural gas plant, and an oil refinery

to refine the crude sent from Venezuela." Those are still

under construction but almost finished.

On May 4, Sanderson sent a second cable explaining that

Lecorps "gave the four oil companies operating in Haiti until

July 1 to sign the GoH contract on Petrocaribe," hoping that

they "will sign the agreement voluntarily, instead of passing

legislation obliging oil companies operating in Haiti to

participate in the Petrocaribe agreement." After talking to

ExxonMobil Caribbean Sales Manager Bill Eisner, the Embassy

reported that Eisner "was shocked when he realized that

Lecorps expected the oil industry to coordinate the PetroCaribe

deal on behalf of the GoH" which would "make the oil

industry prisoner to two incompetent governments," Haiti and

Venezuela, in Sanderson’s words.

Meanwhile, Préval continued trying to bluff Sanderson that

things were not so rosy with the Venezuelans, this time sending

Senate President Joseph Lambert to deliver the spin. Lambert "described

a ‘very tense’ atmosphere behind the scenes of the ALBA summit

between President Préval and President Chavez in a meeting with

Embassy staff on May 4," Sanderson’s Public Affairs Officer

James Ellickson-Brown reported in a May 7 cable. "According

to Lambert, Préval refused to join ALBA and told Chavez that if

ALBA membership were a condition for Venezuelan aid, he would

leave the summit," he wrote. "Lambert added that Préval

and Chavez also clashed over drug-trafficking, diplomatic

representation, what to wear to the summit's closing ceremony

(Chavez wanted everyone in red), and the terms of the energy

agreement Chavez offered Haiti." Lambert said that "Préval

would never do anything to compromise relations with his

‘friends to the North’" and that Chavez "complained that

for all the he gives to Haiti, the Haitians give nothing in

return." Lambert trumpeted that "Préval's resistance to

signing the ALBA accords so upset Chavez that the Cubans tried

to get Préval to play along," but "Préval stood firm, in

the end agreeing only to a ‘very general’ cooperation agreement."

The Americans clearly felt Lambert’s report was a little

fishy, prompting the Political Counselor to ask "why Préval

had not shared some of this with the Ambassador during their meeting," Ellickson-Brown wrote. "Lambert replied that

Préval would be uncomfortable revealing details regarding such a sensitive subject."

Despite the Embassy’s misgivings, Sanderson chose to take

Lambert at his word when reporting to Washington on May 24, just

prior to Préval’s trip there to meet President Bush. She said

that Préval "appears to be losing patience: Lambert told

Emboffs [Embassy officers] that Préval took an anti-ALBA stance

during private meetings with Chavez at the ALBA summit in April,

telling Chavez he can keep his aid if ALBA membership is a

condition." She judged that Préval was coming to the

realization that "seeing is believing when it comes to

promises from Venezuela, and Chavez' words are empty until he arrives with

cash in hand."

Perhaps this generous appraisal explains why Bush

administration officials were so nice to their wayward ally when

Préval visited Washington a few days later. "Préval was very

pleased with the reception he received from President Bush,

Secretary Rice, other USG officials and members of Congress,"

Sanderson reported in a May 29 cable, and he "was neither

surprised nor taken aback by President Bush's concerns regarding

Haitian-Venezuelan relations." Nonetheless, "Préval's

visit appears to have underlined for the delegation the

importance of the Haiti-U.S. partnership and their need to

cultivate Washington decision-makers," Sanderson reported,

while expressing "hope that President Bush's clear message on

Venezuela sank in, but only time will tell."

"Stonewalling" of PetroCaribe Continues

Two weeks after Préval’s return, a transport strike on June

12 and 13, 2007 "gripped Haiti's major cities and underscored

a mounting crisis over fuel prices, which rose nearly 20% in

just two weeks," the IPS reported. Many in Haiti believed

that Haiti’s joining PetroCaribe "would alleviate high

gasoline costs," and word was leaking out that "the two

large US oil companies that export to Haiti are said to have

stonewalled negotiations" for PetroCaribe’s implementation.

The July 1 deadline for PetroCaribe compliance was fast

approaching.

"Negotiations between the GOH and fuel vendors operating

in Haiti to implement the PetroCaribe agreement with Venezuela

remain stalled," Ambassador Sanderson begins a Jul. 20 cable.

Oil company "representatives seem to accept that the

government may eventually force them to accept PetroCaribe terms,

but in the near term, they appear to hold most of the

negotiating cards" because "in light of Haiti's weak

infrastructure and precarious distribution system, the departure

of any of the four companies from the market could severely

disrupt the supply of gasoline throughout the country."

The stand-off over PetroCaribe would continue throughout the

rest of 2007 with Chevron the most resistant to working within

the PetroCaribe framework. But Haiti needed Chevron to ship the

oil from Venezuela.

"It was ridiculous because they had been buying and

shipping petroleum products from Venezuela for 25 years,"

said Michael Lecorps when asked by Haïti Liberté last

week why Chevron put up such a fight. "And you know, Chevron

is an American company, so maybe there were some politics behind

that too, maybe because of Venezuela and Chavez. But they never

said anything about that."

Indeed, the cables suggest that Lecorps’ suspicions that

Chevron had a political beef are correct. After returning to

Haiti on Dec. 22, 2007 from a PetroCaribe summit, Préval

announced the negotiations with Chevron were nearing a close. "We're

going to sign with Chevron and then we're going to start

ordering oil," he said at the airport, reported the AP,

adding that Venezuelan technicians would visit Haiti to consult

on the project. But "Chevron management in the U.S. does not

want to make a lot of ‘noise’ about the agreement because they

do not want to appear to support PetroCaribe," Sanderson

explained in a Feb. 15, 2008 cable. The AP also reported that "Chevron

officials at the company’s San Ramon, California, headquarters

did not respond to requests for comment."

Sanderson explained that the deal was sealed when "Chevron

finally obtained its desired terms from the GOH" whereby the

Venezuelan state-owned oil company Petroleum of Venezuela, Inc.

or PDVSA "will sell to the GoH, which will then sell to

private oil traders, who finally will sell to the oil companies

in Haiti for distribution... Chevron also agreed to ship the

refined petrol on one of its tankers. The GoH expects to receive

a PetroCaribe shipment in late February or early March."

And PetroCaribe shipments, covering all of Haiti’s fuel needs,

did begin on March 8, 2008, marking a victory for Venezuela and

Haiti in surmounting the roadblocks thrown up by the U.S.

Embassy and oil companies.

Préval strictly paid his oil bills, despite having to borrow

money from the PetroCaribe fund following the disastrous events

of September 2008, when four tropical storms slammed Haiti in as

many weeks. "The Sixth PetroCaribe Summit in St. Kitts on

June 12 [2009] congratulated Haiti as the ‘best payer’ out of [PetroCaribe’s]

13 countries, having paid approximately USD 220 million to

Venezuela," reported Tighe in a June 19, 2009 cable. "As

of April 30, Haiti's PetroCaribe account (after Haiti's

withdrawal of USD 197 million for its emergency response to the

2008 hurricanes), had a balance of USD 58.5 million. On May 27,

the Government of Haiti (GOH) announced that its total fuel

imports under PetroCaribe, since the first shipment was received

in March 2008, amounts to approximately USD 489 million. Haiti's

long-term debt, payable over 17 to 25 years, amounts to

approximately USD 240 million."

Tighe also reported that Chavez renewed his pledge, made at

the July 2008 PetroCaribe Summit, to construct an oil refinery

in Haiti. "Lecorps put its capacity at 20,000 bpd [barrels

per day] and the cost at USD 400 million," Tighe wrote. He

also noted that although Haiti was not an ALBA member, "a

tripartite (Haiti-Venezuela-Cuba) energy cooperation agreement

is waiting to be ratified by Parliament" whose "purpose

is to decide how 10% of funds from Haiti's PetroCaribe revenue

would be spent on social programs in Haiti."

Tighe continued: "Lecorps stated that PetroCaribe ‘...is

very good for the country.’ He noted that Venezuelan-financed

electricity generating plants are operating in Port-au-Prince

[30 megawatts], Gonaïves and Cap Haïtien [15 megawatts each] and

have led to longer hours of power in those areas. Haiti receives

shipments of PetroCaribe fuel every two weeks... Lecorps

asserted that Haiti is satisfied with the PetroCaribe agreement

and that it should not be ‘politicized.’"

But politicized it was, and Tighe sounded the alarm,

concluding: "In addition to three power plants already in

operation and promises to modernize the airport in Cap Haïtien,

Venezuela's oil refinery project... would expand Venezuelan and

Cuban influence in Haiti."

Aftermath of a Struggle

Haiti’s Parliament did ratify the Tripartite agreement

between Haiti, Venezuela and Cuba in late 2009, and in October

2009, Dinasa acquired Chevron’s assets and operations in Haiti,

which included 58 service centers, the country’s largest gas

station network. Shell Oil tankers now transport the PDVSA oil

from Venezuela to Haiti, Lecorps told Haïti Liberté.

Under the current PetroCaribe terms, Haiti pays up front 40%

to 70% of the value of the petroleum products it imports from

Venezuela – asphalt, 91 and 95 octane gas, heavy fuel oil

(mazout), diesel and kerosene – with the remaining 60% to 30%

paid over 25 years, with a two year grace period, at an annual

interest rate of 1%.

The U.S. Embassy’s campaign against the South-South

cooperation represented by PetroCaribe – which provides such

obvious benefits for Haiti – reveal the ugly nature and true

intentions of "Haiti's most important and reliable bi-lateral

partner," as Sanderson calls the U.S.

Préval and his officials employed a preferred form of Haitian

resistance, which dates back to slavery, known as "marronage,"

where one pretends to go along with something but then does the

opposite surreptitiously. The U.S. got wise to this tactic and

began to doubt Préval’s reliability. This is why Washington

moved so forcefully to see that Martelly and his crew of

pro-American Haitian businessmen were put in power.

So now we may see a marked shift in Haiti's political

direction. Instead of Préval, who tried to walk the battle-line

between Washington and the ALBA alliance, we find a pro-coup,

long-time Miami resident in power who makes no secret of his

antipathy towards Haiti's "stinking" masses, as he

described them in a YouTube video.

"We have been on the wrong road for the past 25 years,"

Martelly recently declared, placing Haiti's wrong turn, in his

opinion, at about the time of the U.S.-backed Duvalier

dictatorship's fall and the emergence of the democratic

nationalist movement that became know as the Lavalas. Martelly

had a pre-inauguration meeting not with Venezuela's Foreign

Minister, but with that of Colombia, whose development plan he

has said he will emulate.

His reception by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, after

his highly controversial and fraud-marred election, was

exceedingly warm.

All of this augurs woe for Cuban and Venezuelan projects in

Haiti, and possibly for the PetroCaribe agreement, despite its

tremendous and evident contribution to the Haitian people's

welfare.

(Please consider donating to Haiti Liberté to support

our efforts to publish analysis about these secret cables. Visit

our homepage and click on the

Donate button)