|

The U.S. Embassy in Haiti worked closely

with factory owners contracted by Levi’s, Hanes, and Fruit of

the Loom to aggressively block a paltry minimum wage increase

for Haitian assembly zone workers, the lowest paid in the

hemisphere, according to secret State Department cables.

The factory owners refused to

pay 62 cents an hour, or $5 per eight-hour day, as a measure

unanimously passed by the Haitian parliament in June 2009 would

have mandated. Behind the scenes, the factory owners had the

vigorous backing of the U.S. Agency for International

Development (USAID) and the U.S. Embassy, show secret U.S.

Embassy cables provided to Haïti Liberté by the

transparency-advocacy group WikiLeaks.

The minimum daily wage had been

70 gourdes or $1.75 a day.

The factory owners told the

Haitian parliament that they were willing to give workers a mere

9 cents an hour pay increase to 31 cents an hour – 100 gourdes

daily – to make T-shirts, bras and underwear for U.S. clothing

giants like Dockers and Nautica.

To resolve the impasse between

the factory owners and parliament, the State Department urged

then Haitian President René Préval to intervene.

“A more visible and active

engagement by Préval may be critical to resolving the issue of

the minimum wage and its protest ‘spin-off’ -- or risk the

political environment spiraling out of control,” warned U.S.

Ambassador Janet Sanderson in

a June 10, 2009 cable to

Washington.

Two months later, Préval

negotiated a deal with Parliament to create a two-tiered minimum

wage increase – one for the textile industry at $3.13 (125 gourdes) per day and one for all other industrial and commercial

sectors at $5 (200 gourdes) per day.

Still, the U.S. Embassy was not

pleased. Deputy Chief of Mission David E. Lindwall said the $5 a

day minimum “did not take economic reality into account”

but was a populist measure aimed at appealing to “the

unemployed and underpaid masses.”

Haitian advocates of the

minimum wage argued that it was necessary to keep pace with

inflation and alleviate the rising cost of living. As it is,

Haiti is the poorest country in the hemisphere and the World

Food Program estimates that as many as 3.3 million people in

Haiti, a third of the population, are food insecure. Haiti had

been rocked by the so-called “clorox” food riots of April 2008,

named after hunger so painful that it felt like bleach in your

stomach.

According to a 2008 Worker

Rights Consortium study, a working class family of one working

member and two dependents needed a daily wage of at least 550

Haitian gourdes, or $13.75, to meet normal living expenses.

The revelation of U.S. support

for low wages in Haiti’s assembly zones was in a trove of 1,918

cables provided to Haiti Liberté by WikiLeaks.

“As a matter of policy, the

Department of State does not comment on documents that purport

to contain classified information and strongly condemns any

illegal disclosure of such information,” the U.S. Embassy’s

Information Officer Jon Piechowski told Haïti Liberté in

response to a request for a statement. “In Haiti,

approximately 80% of the population is unemployed and 78% earns

less than $1/day – the U.S. government is working with the

Government of Haiti and international partners to help create

jobs, support economic growth, promote foreign direct investment

that meets ILO labor standards in the apparel industry, and

invest in agriculture and beyond.” (According to the UN, 78%

of Haitians live on less than $2, not $1, a day.)

For a 20 month period between

early February 2008 and October 2009, U.S. Embassy officials

closely monitored and reported on the minimum wage issue. The

cables show that the Embassy fully understood the popularity of

the measure.

The cables said that the new

minimum wage even had support from a

majority of the Haitian

business community “based on reports that wages in the

Dominican Republic and Nicaragua (competitors in the garment

industry) will increase also.”

Still, the proposal engendered

fierce opposition from Haiti’s tiny assembly zone elite, which

Washington had long been supporting with direct financial aid

and free trade deals.

In 2006, the U.S. Congress

passed the Haitian Hemispheric Opportunity through Partnership

Encouragement (HOPE) bill, which gave Haitian assembly zone

manufacturers preferential trade incentives. Two years later,

Congress passed an even more generous version of the duty-free

trade bill called HOPE II, and USAID provided technical

assistance and training programs to factories to help them

expand and take advantage of the new legislation.

U.S. Embassy cables claimed

that those efforts were imperiled by parliamentary demands for a

wage hike to keep pace with soaring inflation and high food

prices. “[Textile i]ndustry representatives, led by the

Association of Haitian Industry (ADIH), objected to the

immediate HTG 130 (USD 3.25) per day wage increase in the

assembly sector, saying it would devastate the industry and

negatively impact the benefits of the Haitian Hemispheric

through Opportunity Partnership Encouragement Act (HOPE II),”

said a

June 17, 2009, confidential cable

from Charge d'Affaires

Thomas C. to Washington.

Ironically, Tighe’s

confidential cable one week earlier, on June 10, noted that the ADIH study had found that “overall, the average salary for

workers in the [garment assembly] sector is HTG 173 (USD 4.33),”

only 67 cents a day less than the proposed minimum wage.

Nonetheless the study urged opposing any rise in the minimum

wage because “the current salary structure promotes

productivity and serves as a competitive wage in the region.”

Tighe notes, however, in his next sentence that the “minimum

salary for workers in the Free Trade Zone on the Haiti-DR border

is approximately USD 6.00,” a full dollar more than the 200

gourdes ($5) demanded. Still, the ADIH report concluded somehow

“that a minimum daily wage of HTG 200 would result in the

loss of 10,000 workers,” more than one third of Haiti’s

27,000 garment workers at that time.

Tighe said that the “ADIH

and USAID funded studies on the impact of near tripling of the

minimum wage on the textile sector found that an HTG 200 Haitian

gourde minimum wage would make the sector economically unviable

and consequently

force factories to shut down.”

Bolstered by the USAID study,

the factory owners lobbied heavily against the increase, meeting

President Préval on multiple occasions and more than 40 members

of Parliament and political parties, according to the cables.

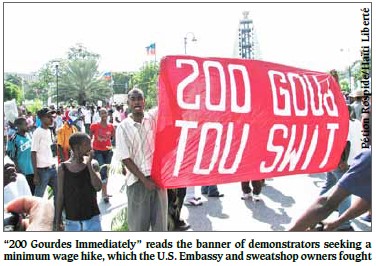

The Haiti cables also reveal

how closely the US Embassy monitored widespread pro-wage

increase demonstrations and openly worried about the political

impact of the minimum wage battle. UN troops were called in to

quell student protests, sparking further demands for the end of

the UN military occupation of Haiti.

On Aug. 10, 2009, garment

workers, students and other activists demonstrated at the

Industrial Park (SONAPI) near the Port-au-Prince airport. The

police arrested and carted away two students, Guerchang Bastia

and Patrick Joseph, on the charge of inciting the workers.

Demanding their immediate release, the protestors marched to the

Delmas 33 police station, where the police fired tear-gas and

the throng replied with rock-throwing. In the course of the

demonstration, the windshield of U.S. Chargé d’Affaires Tighe’s

vehicle was smashed, and he took refuge in the police station.

Later, when journalists asked him about the incident and the

minimum wage controversy, Tighe wouldn’t comment but just said

that “it is always a minority which creates disorder.”

Due to the fierce

demonstrations of workers and students, sweatshop owners and

Washington won only a partial victory in the minimum wage

battle, delaying the $5/day minimum for one year and keeping the

assembly sector’s minimum wage a notch below all other sectors.

In October 2010, assembly workers’ minimum wage increased to 200 gourdes a day, while in all other sectors it went to 250 gourdes

($6.25).

“Every time the minimum wage

has been discussed, [the assembly industry bourgeoisie in] ADIH

has cried wolf to scare the government against its passage: that

raising the minimum wage would mean the certain and immediate

closure of industry in Haiti and the cause of a sudden loss of

jobs,” wrote the Haitian Platform for Development

Alternatives (PAPDA) in a June 2009 press release. “In every

case, it was a lie.”

(Please consider donating to Haiti

Liberté to

support our efforts to publish analysis about these secret

cables. Visit our homepage and click on the Donate button at the

top, or visit this link: http://goo.gl/oY7ct )

|