Even before the

Haitian government authorized it, Washington began deploying

22,000 troops to Haiti after the Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake,

despite U.S. Embassy officials saying there was no serious

security problem, according to secret U.S. diplomatic cables

provided to Haïti Liberté by the media organization

WikiLeaks.

Washington’s decision to send thousands of troops in response to

the 7.0 earthquake that rocked the Haitian capital and

surrounding areas drew sharp criticism from aid workers and

government officials around the world. They criticized the

militarized response to Haiti’s humanitarian crisis as

inappropriate and counterproductive, claiming Haiti needed “gauze

not guns.” French Cooperation Minister Alain Joyandet

famously said that international aid efforts should be “about

helping Haiti, not about

occupying Haiti.”

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez also decried “Marines armed

as if they were going to war,” in his weekly television

address. “There is not a shortage of guns there, my God.

Doctors, medicine, fuel, field hospitals, that is what the

United States should send.

They are occupying Haiti in an undercover manner."

The

earthquake-related cables show that Washington was very

sensitive to international criticism of its response, and U.S.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton mobilized her diplomatic

corps to ferret out “irresponsible journalism” worldwide

and “take action” to “get the narrative right.”

Meanwhile, the UN in Haiti claimed its 9,000 occupation troops

and policemen were sufficient to ensure security. On Jan. 19,

with Resolution 1908, the UN Security Council unanimously

approved sending more than 3,500 reinforcements to Haiti “to

support the immediate recovery, reconstruction and stability

efforts,” increasing MINUSTAH (UN Mission to Stabilize

Haiti, as the occupation force is called) to 12,651.

But Obama administration officials said the additional U.S.

troops were necessary.

"Until

we can get ample supplies of food and water to people, there is

a worry that in their desperation some will turn to violence,”

Secretary of Defense Robert Gates told reporters six days after

the quake. “And we will work with the UN in trying to ensure

that the security situation remains good."

Seeking

to avoid the appearance of a unilateral U.S. military action,

the U.S. asked Préval to issue a joint communique with U.S.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on Jan. 17.

Haiti “requests

the United States to

assist as needed in augmenting security,”

said the communiqué, providing the rationale for what would be

the third U.S. military intervention of Haiti in the last 20

years.

The

revelations that US officials in Port-au-Prince did not believe

there was, in fact, a security threat to justify a military

intervention come in a trove of 1,918 cables made available to

Haïti Liberté by WikiLeaks.

Deployment

First, Authorization Later

After the quake,

Haiti’s capital Port-au-Prince resembled a warzone. Bodies lay

strewn, collapsed buildings spilled into dust-filled streets,

while Haitians frantically rushed to dig out survivors crying

out from under hills of rubble. Several flattened neighborhoods

looked as if they had been destroyed by bombing raids.

But the

one element missing from this apocalyptic scene was an actual

war or widespread violence. Instead, families sat down in the

street, huddled around flickering candles with their

belongings. Some wept, some sat in shell-shocked silence, while

others sang prayers, wailing for Jesus Christ in Kreyòl, “Jezi!”

In the

quake’s chaotic aftermath, Haitian President René Préval and his

prime minister, Jean-Max Bellerive, were out of touch with U.S.

government officials for about 24 hours. When they did connect,

the Haitian leaders held a 3 p.m. meeting on Jan. 14 with U.S.

Ambassador Kenneth Merten, the Jamaican Prime Minister, the

Brazilian and EU ambassadors, and UN officials.

President Préval laid out priorities: “Re-establish telephone

communications; Clear the streets of debris and bodies; Provide

food and water to the population; Bury cadavers; Treat the

injured; Coordination” among groups amidst the catastrophic

destruction, a

Jan. 16, 2010 cable explains. Préval did not

mention insecurity as a major concern. He did not ask for

military troops.

But the

same cable reports that “lead elements of the 82nd Airborne

Division arrived today, with approximately 150 troops on the

ground. More aircraft are expected to arrive tonight with troops

and equipment.”

The U.S. government had already initiated the deployment of

considerable military assets to Haiti, according to the secret

State Department cables. At its peak, the U.S. military response

included 22,000 soldiers -- 7,000 based on land and the

remainder operating aboard 58 aircraft and 15 nearby vessels,

according to the Pentagon. The U.S. Coast Guard was also flying

spotter aircraft along Haiti’s coast to intercept any refugees

from the disaster.

A

Jan.

14 cable from Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to U.S.

embassies and Pentagon commands worldwide said that the U.S.

Embassy in Haiti “anticipates significant food shortages and

looting in the affected areas.” But

subsequent dispatches

from Ambassador Merten in Haiti repeatedly describe only “sporadic”

incidents of violence and looting.

In those

early post-quake hours, it appears that Préval was reluctant to

call in U.S. troops. A

Jan. 19 cable reported that a “radio

talk show host blasted President Préval on Signal FM on January

18 for hesitating to authorize the

U.S. military to deploy.”

But

Washington wasn’t waiting for authorization apparently. In a

Jan. 15 cable, Clinton told diplomatic posts and military

commands that “approximately 4,000

U.S. military personnel will be in

Haiti by January 16 and 10,000 personnel by January 18.”

However, not until two days later, on

Jan. 17, did Clinton and

Préval issue the “joint communique” in which Haiti

requested the U.S. “to assist as needed in augmenting

security.”

Aware

that there would be international dismay about U.S. troops

playing a security role, Clinton outlined a series of “talking

points” for diplomats and military officers in

her Jan. 22

cable. She said they should emphasize that “MINUSTAH, has the

primary international responsibility for security,” but that

“in keeping with President Préval's request to the United

States for assistance to augment security, the U.S. is

providing

every possible support... and is in no way supplanting the UN's

role.”

UN Says It

Should Provide Security

In the Jan. 18

meeting between Préval and international officials in Santo

Domingo, former Guatemalan diplomat Edmund Mulet, MINUSTAH’s new

chief, said that his troops “were capable of providing

security” in the country. (Mulet had flown into Haiti on a

Pentagon plane to take over from MINUSTAH chief Hédi Annabi, who

was killed with 101 other UN personnel when the Hotel

Christopher, which acted as UN headquarters, collapsed in the

quake.) Mulet “insisted that MINUSTAH be in charge of all

security in Haiti, with

other foreign military forces limited to humanitarian relief

operations.”

In fact, many Haitians looked on in disbelief as heavily armed

UN soldiers, after rushing to rescue their own personnel,

resumed driving through the devastated capital and its suburbs

in armored troop carriers, bristling with the guns. Many

Haitians have long resented and denounced the MINUSTAH as a

flagrant violation of Haiti’s 1987 Constitution and an affront

to Haitian sovereignty. The UN troops brandishing guns in front

of devastated earthquake victims added insult to injury.

Even

before the earthquake, President Préval had called on the UN to

change its mission from costly, mostly pointless, and sometimes

repressive military patrols to building desperately needed

infrastructure. “Turn your tanks into bulldozers” Préval

pleaded in his 2006 inaugural speech. UN and U.S. officials

repeatedly and dismissively rebuffed the request.

After

the quake, Brazilian Defense Minister Nelson Jobim and

Organization of American States (OAS) Representative to Haiti

Ricardo Seitenfus echoed Préval’s call. Even Mexico “sought

an unproductive debate on reviewing MINUSTAH’s mandate” at

the UN Security Council, a proposal which was thankfully “avoided,”

a Feb. 24, 2010 cable from the U.S. Mexican Embassy reported.

Even though the UN boosted its force, US troops in and around

Haiti eventually outnumbered it by almost 2-to-1, and they

remained for six months. Those troops poured into Haiti as U.S.

officials fretted about the Haitian police force’s ability to

reorganize itself and maintain order, the cables show. (At the

same time, the cables reported no marked increase in violence.)

But following her boss’ “talking

points,” Cheryl Mills, Clinton’s Chief of Staff, “assured

Préval... that the [U.S.]

military was here for humanitarian relief and not as a security

force,” explains a Jan. 19

cable.

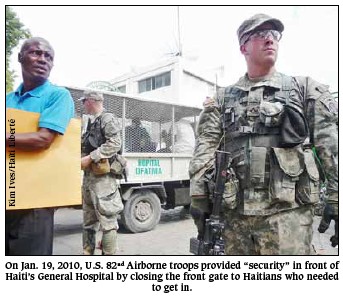

But that’s not what journalists on the ground saw.

On Jan.

19, 2010, Democracy Now’s crew along with Haïti

Liberté’s Kim Ives arrived at the General Hospital around 1

p.m., shortly after troops from the 82nd Airborne

Division. There, they found the soldiers, guns in hand, standing

behind the hospital’s closed main gate. The troops had orders to

provide “security” by denying entrance to a crowd of

hundreds, including injured earthquake victims and family

members of patients bringing them food or medicine. “Watching

the scene in front of the

General Hospital yesterday said it

all,” said Ives in a

Democracy Now! interview the next day. “Here were people

who were going in and out of the hospital bringing food to their

loved ones in there or needing to go to the hospital, and there

were a bunch of... U.S.

82nd Airborne soldiers in front yelling in English at this

crowd. They didn’t know what they were doing. They were creating

more chaos rather than diminishing it. It was a comedy, if it

weren’t so tragic... They had no business being there.”

The

journalists finally managed to get into the hospital and alerted

the hospital’s interim director, Dr. Evan Lyon, about the

problem. He immediately sent word down that the soldiers should

stand down and open the gate. They did, but then assumed

positions in the hospital’s driveway, continuing to act, among

the injured hobbling into the hospital, as a completely

unnecessary and unrequested “security force,” contrary to

what Mills had promised Préval.

The

entry point for much of the military personnel and equipment was

the capital’s Toussaint L’Ouverture Airport. Timothy Schwartz,

an anthropologist who has consulted for USAID, rushed into

Port-au-Prince the day after the quake to help. “Ben and I

are at the airport, on the tarmac, helping soldiers of the 82nd

Airborne load thick, heavy metal plates into the back of my

pickup truck,” he writes in a forthcoming book. “Then it

occurs to me, ‘what the hell are these things?’”

“‘Body

armor,’ Ben says.”

Schwartz reflected: “Fear must be the reason why all this

military hardware and these soldiers around us are setting up

base camp behind a ten foot fence. Fear must be why they are

walking around in the near sweltering heat with 80 pounds of

gear strapped to their bodies and machine guns swung over their

shoulders.”

One

doctor from Colorado who flew in with colleagues (at their own

expense) on Jan. 17 to help the injured was shocked by the

military deployment he saw at the airport. “We need gauze,

not guns,” he told the Democracy Now crew.

The enormous influx of U.S. military personnel, weapons and

equipment into the airport prompted a chorus of protest from

mid-level French, Italian, and Brazilian officials, as well as

the aid group Doctors Without Borders. They were outraged that

planes carrying vital humanitarian supplies were prevented from

landing, or delayed, sometimes for days.

“We

had a whole freaking plane full of the friggin’ medicine!”

Douglas Copp, an American rescue worker, exclaimed outside a UN

base not long after the quake. The U.S. military, which had

taken over the Port-au-Prince airport, would not give clearance

for the Peruvian military plane to land. It had to divert to the

Dominican capital, 150 miles away. “In

Santo Domingo, we got a bus, and we

came into Haiti with just the things we could fit in the bus,”

he said.

Getting the

Narrative “Right”

Secretary Clinton

brooked no criticism, which was growing worldwide, of the U.S.

military’s role in the relief effort.“I am deeply concerned

by instances of inaccurate and unfavorable international media

coverage of America's

role and intentions in Haiti,”

she wrote in a stern

Jan. 20 message to embassies across the

globe. “It is imperative to get the narrative right over the

long term.”

She

asked that Embassies report back to her, “citing specific

examples of irresponsible journalism in your host countries, and

what action you have taken in response.”

In countries all over the world, from Luxembourg to Chile,

diplomatic officials scrutinized the media and hit back against

criticism of the U.S. military’s build-up in Haiti, sending back

dozens of detailed reports.

For

example,

a Jan. 20 cable from Doha describes an Al Jazeera English report on the relief effort’s

militarization which compared the US-run airport to a “mini-Green

zone.” This report resulted in a phone call “during the

early morning hours of January 18" from the U.S. Embassy in

Doha to Tony Burman, managing

director of Al Jazeera English.

But

the airport story was accurate. “They had taken over the

place,” said Jeremy Dupin, 26, about the U.S. “joint

coordination” of the airport. After his home had collapsed,

Dupin, a Haitian journalist, had wandered the streets for a day

until linking up with an Al Jazeera English crew to work as a

producer.

“There

were 20,000 soldiers so this was a big move,” Dupin said. “We

pointed out there were serious problems, and that's why the

U.S. didn't like the news,

but we told the truth. And if we had to say it again, we would

say it again... This wasn't something we just said, it's

something we showed with images and footage. I mean, this was

the truth.”

Many

cables reported generally positive coverage in their countries.

But any instance of negativity towards the United States, no

matter how small, was flagged and dealt with. In Colombia, for

example, “the only negative coverage” was from a

newspaper cartoonist who drew “a colonial soldier planting a

U.S. flag on the island

of Haiti,” the

Bogota

Embassy reported on Jan. 26. “Post will meet with the

cartoonist this week to discuss this cartoon with him and

provide information refuting its inference, as well as engage

with El Espectador's editor to express our strong concerns.”

The

Buenos Aires Embassy reported on Jan. 26 that the “pro-government,

left-of-center Pagina 12 protests the excessive U.S. troop

deployment, noting that ALBA (Bolivarian Partnership for the

Americas) voiced its ‘concern over the excessive presence of

foreign troops without any reason, purpose, venues or time of

permanence,’ in veiled reference to the U.S. troops.”

Factory Owners

Demand “Security at All Levels”

Back in Haiti,

Embassy officials worried that only 30-40% of the police were

showing up for duty, while some 4,000 prisoners had escaped from

the National Penitentiary. There were “numerous gang

member/leaders” among the escapees,

a Feb. 16 cable noted,

but “many were not hardened criminals and were being held in

lengthy pre-trial detention, never having been sentenced.”

“The

security situation is worsening,” said

a Jan. 18 cable

issued just after midnight. “[E]scaped inmates have formed

gangs to kidnap and perpetuate [sic] other crimes.”

Only

nine hours later, however,

another dispatch: “Embassy

Port-au-Prince reports security is ‘pretty good,’ with ‘sporadic

outbreaks’ of violence, despite news stories of a growing number

of looters roaming the streets of Port-au-Prince and of gunfire

and police using tear gas to disperse crowds.”

A

Jan. 23 cable shows the situation unchanged: “Embassy

Port-au-Prince reports the

security situation on the ground remains relatively calm.”

Many

news stories dishonestly described a sensational and imaginary

eruption of violence in Haiti. “Gangs Rule Streets of

Haiti,”

CBS reported the day after the quake. On Jan. 19, CNN.com’s lead

headline was “Security fears grow in

Haiti’s tent cities,”

and the caption below, “with 4,000 convicted criminals on the

loose, nothing and no one is safe.”

But

the U.S. Embassy was reporting the opposite. One

Jan. 19 cable

said that the “security situation in

Haiti remains calm overall with no

indications of mass migration towards North America.”

Another Jan. 19 cable said: “Despite hardships in devastated

neighborhoods, residents appear to be calm and civil, though

isolated reports of roving armed gangs continue.” It

continued: “Residents were residing in made-shift [sic] camps

in available open areas, and they had not yet received any

humanitarian supplies from relief organization. Nonetheless, the

residents were civil, calm, polite, solemn and seemed to be

well-organized while they were searching for belongings in the

ruins of their homes. However, isolated reports continue of

roving armed gangs engaged in looting and robbery.”

The

U.S. moved aggressively to beef up the Haitian police (PNH),

giving police chief Mario Andrésol “command and control

advice and mentoring” from Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and

FBI agents while trying to ensure that Haitian police officers

were paid and well-equipped. The DEA advisor was Darrel Paskett,

whose first post-quake priority was directing his “well-armed”

bulletproof-vested DEA agents to guard the U.S. Embassy from “huge

crowds” of desperate Haitians that might overrun it,

FOX

News reported. The crowds never materialized.

Before the end of the month,

three separate State Department

cables relayed that “Canadian Embassy contacts in

Port-au-Prince report verbal orders

were allegedly given by police leadership to shoot escaped

prisoners on sight. UN Civilian Police officers close to prison

authorities also heard unconfirmed reports of extra-judicial

killings by police.”

The

cables do not identify what action, if any, the PNH’s U.S.

advisors took to investigate or stop the unlawful killings. Nor

is there any mention of the numerous so-called “looters”

in downtown Port-au-Prince’s rubble-filled commercial district

who were shot on sight by the Haitian police, like 15-year-old

Fabienne Cherisma, who grabbed some paintings from a collapsed

structure.

Not

surprisingly, Haitian business owners were the most worried

about security, especially for their factories. Five days after

the quake, Ambassador Merten

met with representatives of Haiti’s

business sector, who said “their major concern is security at

all levels, to include security of goods, at marketplaces, and

for ports of entry.”

Later, they asked the UN occupation

troops “to provide security for reopened factories, and

pledged to re-open in weeks.” Embassy officers met again

with Haitian business leaders one week later.

In

a

Jan. 26 cable, Merten commented that “apparel manufacturers

in Haiti operate on a

high volume, thin margin, low capitalization basis where cash

flow is extremely important for the business to survive.”

He relayed a factory owner’s suggestion for a $20 million loan

to the sector. Days later, he applauded the introduction of

legislation in the U.S. Senate “intended to provide

short-term relief to

Haiti's apparel sector” by

extending trade preferences.

Militarization

of Humanitarian Aid

There is no doubt

that the U.S. soldiers deployed to Haiti helped many earthquake

victims. The 82nd Airborne Division helped set up one of the

capital’s largest and best equipped IDP camps of over 35,000

with actor Sean Penn at the Pétionville Country Club, which was

their operational base.

The

Pentagon’s earthquake response also included one of the largest

medical outreach efforts in history. Service men and women

treated and evaluated thousands of Haitian patients, including

more than 8,600 on the Navy hospital ship USNS Comfort. Surgeons

aboard the ship completed nearly 1,000 surgeries.

However, even more impressive results were obtained by Cuba’s

800 doctors in Haiti and the Henry Reeve Medical Brigade, a

1,500 member contingent of doctors from Cuba and many other

nations who graduated from Cuba’s medical school. In the six

months after the quake, according the Cuban Embassy in Haiti,

the Brigade treated over 70,300 patients, performing over 2,500

operations, all without deploying soldiers or bringing in

weapons. (Cuba’s medical missions are still in Haiti and remain

a bulwark against cholera’s spread.)

In

fact, there is a growing movement among aid groups worldwide,

and even in the UN, against the militarization of humanitarian

aid. The report entitled "Quick Impact, Quick Collapse: The

Dangers of Militarized Aid in Afghanistan" by Actionaid,

Oxfam International, and other NGOs could have been as easily

written about Haiti, where the Pentagon’s “government in a

box” strategy was being applied in late January 2010, when

the study was released.

“As

political pressures to ‘show results’ in troop contributing

countries intensify, more and more assistance is being

channelled through military actors to ‘win hearts and minds’

while efforts to address the underlying causes of poverty... are

being sidelined,” the report’s introduction reads. “Development

projects implemented with military money or through

military-dominated structures aim to achieve fast results but

are often poorly executed, inappropriate and do not have

sufficient community involvement to make them sustainable. There

is little evidence this approach is generating stability...”

But no matter where one comes down on the question of the U.S.

military’s role and contribution in post-quake Haiti, one thing

is for sure. The massive troop deployment was set in motion

before President Préval had given any green-light, putting him

before a fait accompli which he had little choice but to go

along with.

“It

is certain that one important reason for the U.S. troop

deployment to Haiti after the quake was to bar any revolutionary

uprising that might have emerged due to the Haitian government’s

near collapse,” said Haitian political activist Ray Laforest,

a member of the International Support Haiti Network. “Also

the perception of Haitians in

Washington, since the time of its 1915

occupation, is that they are savage, undisciplined and violent.

In fact, the 2010 earthquake proved the opposite: Haitians came

together in an exemplary display of heroism, resilience and

solidarity. Washington’s military response to the earthquake

indicates how deeply it misunderstands, mistrusts and mistreats

Haiti.” |