|

First of two articles

Youri Latortue is one of Haiti’s most

powerful politicians.

As an outspoken Senator, he is an ally of

Haitian President Michel Martelly. Both are leading advocates

for reestablishing the demobilized Haitian Army. He supported

Martelly’s nominee for Prime Minister, neoliberal businessman

Daniel-Gérard Rouzier, who was rejected by the Parliament in a

Jun. 21 vote.

But Youri Latortue is also a

drug-trafficker, gang godfather, and death-squad leader,

according to the testimony and reports of many colleagues, crime

witnesses and government officials, both Haitian and

international.

In fact, “Senator Youri Latortue may

well be the most brazenly corrupt of leading Haitian

politicians,” according to the U.S. Embassy. Secret U.S.

State Department cables obtained by the media organization

WikiLeaks and reviewed by Haïti Liberté paint a portrait

of a relentlessly unscrupulous, ambitious strongman, who has

helped bring down Haitian governments and holds Gonaïves,

Haiti’s fourth largest city, as his personal fiefdom.

His Rise to Power

Born in Gonaïves, Youri Latortue went to

law school in Port-au-Prince and then graduated from Haiti’s

military academy in 1990. He became a lieutenant in the Haitian

Armed Forces (FAdH), teaching briefly at the Military Academy.

But after the Sep. 30, 1991 coup d’état against President

Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Latortue joined the Army’s notorious

Anti-Gang Unit (previously called Criminal Research) headed by

Col. Michel François, one of the coup’s principal leaders.

“It was widely known that he was

involved in many of the political killings carried out during

the 1991-94 coup, in particular the shooting of Father

Jean-Marie Vincent in August 2004,” explained a once

highly-placed government security source who wishes to remain

anonymous. “He was one of Michel François’ death-squad

leaders.”

In 2004, a delegation of the Center for the

Study of Human Rights wrote that “a former high-ranking

police official from the USGPN (palace security), Edouard

Guerrière... claims that Youri Latortue participated in the 1994

murder of Catholic priest Jean-Marie Vincent (as did

eyewitnesses in 1995), and that he assisted in the 1993 murder

of democracy activist Antoine Izméry.”

In 2005, a U.S. policeman with the

United Nations Police (UNPOL) videotaped an interview that he

made with a young woman who feared for her life “because the

28th of August 1994, I witnessed Youri Latortue murder the

priest by the name of Jean-Marie Vincent,” she said. The

video, released in October 2010 by the Haiti Information Project

(HIP), is now available on YouTube.

She describes how the priest drove up to

his gate that night. “That's when I saw... a double white

pickup with a bunch of men in black,” she continued. “I

saw Youri... I [didn’t recognize] the other ones. But the reason

why I remember Youri [was] because he used to come to [name

removed] house. And I saw him getting out of the [pick-up]and

shooting at the car. But at that time, I didn't know [the

victim] was a priest... I didn't know the person who was in that

car.” It was only later that she learned who it was (see

Haïti Liberté, Vol.4, No.14, 10/20/2010).

The video-taped interview was sent to

HIP with the following note: “The UN has no interest in

pursuing this case or revealing this evidence despite the

statements of this eyewitness that Youri Latortue was the

triggerman that shot and killed Father Jean-Marie Vincent on

August 28, 1994.... It is a travesty of justice that the UN has

been withholding this testimony from the public. They are

supposed to be impartial but Latortue has powerful friends in

the US Embassy who view him as an asset since his role following

the ouster of Aristide in 2004.”

After Aristide returned to Haiti from exile

on Oct. 15, 1994, he dissolved the FAdH in early 1995, and

Latortue was transferred to the Interim Police force, made up of

former FAdH soldiers. Dr. Fourel Célestin, a former FAdH

colonel, was appointed as President Aristide’s security advisor,

and he proposed bringing Youri Latortue into the Palace security

under his aegis.

“Aristide was dead set against it,

having heard the persistent rumors of Latortue’s murderous role

during the coup,” the former government source said. “But

Célestin convinced him, arguing that the Palace needed to have

some of the Army bad guys if it was going to dismantle and

neutralize the force.” Aristide relented.

In March 1995, unknown assassins shot to

death well-known pro-coup spokeswoman Mireille Durocher-Bertin

and another passenger in her car on the eve of President Bill

Clinton’s visit to Haiti. The shooting was a tremendous

embarrassment to the Aristide government and to Clinton. A team

of FBI agents spent time in Haiti investigating the murder, and

Youri Latortue was one of their suspects. Washington yanked

Latortue’s U.S. travel visa.

Latortue worked out of Célestin’s Palace

office until 1996 when President René Préval took power.

Washington insisted that certain former FAdH officers deemed too

close to Aristide – Célestin, Major Dany Toussaint, Major Joseph

Médard – be removed from leadership of the new police and two

new Palace Security details: the USP (Presidential Security

Unit), similar to the U.S. Secret Service, and the USGPN

(Security Unit to Guard the National Palace). When they were

removed, that left a void in the Palace security’s command, a

void that was filled by Latortue. He became the USGPN’s deputy

chief under Frantz Jean-François. Two better trusted pro-Lavalas

security agents – Nesly Lucien and Oriel Jean – were named to

head the USP. That arrangement lasted throughout Préval’s term

(despite his grave misgivings about Latortue, as we shall see)

until he handed the Presidency back to Aristide in 2001.

Aristide Returns, Youri Takes Leave

“After Aristide's accession, other USGPN

policemen found [Latortue] ‘hostile’ to his new President, who

worried about his involvement in a ‘plot,’ according to Haiti's

elite-owned radio station Signal FM on February 21, 2001,”

Canadian investigative journalist Anthony Fenton wrote in

a June

2005 Znet article entitled “Have the Latortues

Kidnapped Democracy in Haiti?”.

At that point, Latortue was transferred out

of the Palace to work under Nesly Lucien, who had been named

Police Chief. But in late 2001, Latortue took a paid leave of

absence from the police to pursue a master’s degree in law in

Canada. He “had lived in Miami, [and] studied in Montreal for

two years” he told Fenton in a June 2005 phone interview.

It was during that time that Latortue was

paid a visit by Stanley Lucas, an operative for the

International Republican Institute (IRI), a tentacle of the U.S.

government’s National Endowment for Democracy (NED), according

to our security source. IRI was playing a central role in

organizing the “civilian opposition” to Aristide, principally

the so-called “Group of 184,” headed by sweatshop magnate Andy

Apaid. But Lucas was also keeping touch with the “armed

opposition” of former Haitian soldier and police chief Guy

Philippe in the Dominican Republic. This is where Youri came in.

During 2002 and 2003, Latortue shuttled

back and forth between the U.S., Canada, and the Dominican

Republic, meeting with Guy Philippe, former FRAPH death-squad

leader Jodel Chamblain, and others in the “rebel” force forming,

training, and launching raids into Haiti. Interestingly, Youri’s

U.S. travel visa, which had been suspended in 1995, was

reinstated in 2002 when he started to play this role of

anti-Aristide intermediary.

“We know that Youri was one of the

intellectual authors, one of the key planners, behind the Dec.

17, 2001 attack on the National Palace,” when a band of

Philippe’s “rebels” briefly took over the National Palace during

a failed coup attempt, our well-placed source explained. “In

the investigation after the attack, we learned that it was

Youri’s people – his proteges – in the USGPN who, working inside

the Palace, let the attackers into the Palace grounds.”

Finally Latortue, Philippe, Lucas, IRI, and

the 184 were successful in their destabilization campaign after

a U.S. SEAL team kidnapped Aristide from his home on Feb. 29,

2004, completing the second coup against him.

After the 2004 Coup

Youri Latortue then flew back to Haiti with

his first cousin once-removed, Gérard Latortue in tow. A few

weeks later, Gérard Latortue was installed as de facto

Prime Minister. Youri Latortue, often called Gérard’s “nephew,”

was appointed as his security and spy chief, with the title

“Responsible for National Intelligence to the Primature.”

“The thing was that Gérard had been

working for international organizations overseas most of his

life and didn’t really know the lay of the land in Haiti,”

our security source explained. “He had to rely largely on

Youri for guidance. In that sense, Youri was practically the

shadow Prime Minister. And during that coup, he was the main one

responsible for the massacre of many militants in Belair, Cité

Soleil and other pockets of resistance.”

In his post, Latortue was “nicknamed

'Mister 30 Per Cent' because of the percentage he demands in

return for favors,” wrote Thierry Oberlin in the December

21, 2004 Le Figaro. “Worried, not without reason, about his

own security, the prime minister pays 20,000 euros a month to

this former police officer implicated in various scandals for

'organizing an intelligence service'."

But then something interesting happened. In

late 2004, Gérard Latortue left Haiti to travel to a conference

in Canada, passing through Miami. Youri was part of his

delegation. But in Florida, U.S. agents detained Youri for his

suspected involvement in drug-trafficking. (Joel Deeb, a

Haitian-American arms dealer who reportedly brokered deals with

Youri Latortue, “stated that Youri Latortue presently has

four sealed DEA indictments pending against him, and that the

DEA [has] issued an extradition letter for Youri Latortue to the

interim government,”

Fenton learned in several interviews

with Deeb between April and June 2005. “Youri Latortue

himself evaded questions about the DEA indictments, denying that

he and Deeb, as Deeb claims, were in regular contact.”)

Gérard Latortue got on the phone to

officials in Washington and demanded that Youri be released.

Eventually, U.S. officials said they would not hold Youri, but

on the condition that he take the next flight back to Haiti,

which he did.

“When Gérard returned to Haiti after

the Canada visit, he met with Youri about the incident and about

his vulnerability to prosecution,” our source explains. “They

determined that the best course of action was for Youri to

become an elected official, which would confer upon him immunity

from prosecution. That is why and how Youri’s political career

began, assured by Gérard, under whom his election was assured.”

Thus, under his “uncle’s”

government, Youri was elected to a six-year term as the first

senator of the Artibonite Department in the Feb. 7, 2006

elections that also brought Préval to the Presidency for the

second time.

This is where the U.S. Embassy cables pick

up the thread.

A Drug Dealer and Kidnapper in the

Palace?

When Youri Latortue worked in the Palace

under Aristide and Préval, neither president was comfortable

with his presence there and knew he was involved in illegal

activities. But they were afraid to act against him. “Among

political observers, it is an article of faith that Latortue was

involved in drug trafficking under Aristide and during the first

Préval administrations,” reported U.S. Ambassador Janet

Sanderson in a June 27, 2007 cable to Washington. “Préval

himself reports that Latortue ‘ran drugs’ out of his office in

the Presidency during Aristide's mandate.”

Préval said the same thing to Sanderson’s

successor, current Ambassador Kenneth Merten, who reported in an

Oct. 6, 2009 secret cable that the Haitian president “also

expressed concern over the lack of integrity of the president of

the Senate Commission on Justice and Security, Senator Youri

Latortue, implying ties to the drug trade. He supported his

viewpoint by recalling the USG’s [U.S. government’s]alleged

refusal to allow Latortue to travel to the United States” in

1995 and 2004.

The U.S. Embassy treated Latortue warily

when he returned to Haiti in 2004. The first conflict they had

with him was when he took it upon himself to tell “some of

the ex-soldiers in Cap-Haïtien” who had taken part in Guy

Philippe’s “rebel” force “that they would be admitted into

the HNP,” or Haitian National Police. “This raised a

red-flag for us and the rest of the international community and

was a subject of the Core Group meeting March 12,” reported

Sanderson’s predecessor, Ambassador James Foley in a

Mar. 15,

2005 cable. The U.S. and its allies went to Prime Minister

Gérard Latortue who “made clear this was not the case,”

pleasing them with “his public acknowledgment that the HNP

was not an automatic option for the ex-FADH.”

Two months later, a prominent member of

Haiti’s bourgeoisie, businessman Fritz Mevs, told the U.S.

Embassy that “Colombian drug-traffickers” were working “with

a small cabal of powerful and connected individuals, including

Youri Latortue... to create a criminal enterprise that thrives

on - and generates - instability,” Foley wrote in a

May 27,

2005 cable. This cabal which included Youri was a “small

nexus of drug-dealers and political insiders that control a

network of dirty cops and gangs that [...] were responsible for

committing the kidnappings and murders.”

The Embassy also worried that Youri was

beginning to alienate some in the anti-Lavalas coalition that

had driven Aristide from power, particularly students. They were

starting to distrust the Interim Government of Haiti (IGOH), as

the Latortues’ de facto regime was called, because “rumors

are rife that the IGOH (and specifically Youri Latortue) is

building an ‘intelligence cell’ within the student movement for

political ends,” wrote interim Chargé d’Affaires Douglas M.

Griffiths in a

July 6, 2005 cable.

Washington was also closely watching the

emergence of the Artibonite in Action (LAAA), the party Youri

Latortue formed in 2005 to run for Senate. “This party may

have nefarious sources of income and has already been implicated

in gang-related violence in the poorer neighborhoods of Raboteau

and Jubilee in Gonaïves,” wrote another interim Chargé

d'Affaires Erna Kerst in a

Nov. 30, 2005 cable.

As Sanderson took over the Embassy in early

2006, she also echoed that Youri Latortue is “widely believed

to be involved in illegal activities,” in a

Jun. 16, 2006

cable.

Less than two months later, on Aug. 2, she

sent

another cable

that reported that Edmond Mulet, the chief of

the U.N. Mission to Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH), was concerned

that “drug trafficking has become an increasingly

alarming problem, which is difficult to combat, in part because

of the drug ties within the Haitian Government,” Sanderson

wrote. “In this connection, he mentioned Senate leader Joseph

Lambert and Security Commission Chair Youri Latortue --

describing the latter as a ‘drug dealer’.”

Arms dealer Joel Deeb also called Latortue

“a drug smuggling ‘Kingpin,’ with ‘close ties’ to

paramilitary leader Guy Philippe,” Anthony Fenton reported

in his ZNet article. “Deeb also said that ‘everybody knows’

about Youri Latortue's involvement in kidnappings,” which

were plaguing Haiti at the time.

“It is also widely known that Youri

Latortue and his deputy, Jean-Wener Jacquitte,... are, at the

least, funneling money associated with kidnappings,” Fenton

continued. “This has been confirmed by sources both in

diplomatic circles, as well as sources inside and outside the de

facto Haitian government.”

In a

September 2006 cable, Sanderson

reported that Youri was able “to hire his ‘cronies’ to run

customs' operations in Gonaïves” and, in

a November 2006

cable, that Gonaïves Judge Napela Saintil, who had presided over

the landmark 2000 Raboteau Massacre trial (at which Youri

Latortue “refused to testify”), considered Latortue “his

‘arch enemy’” and “accused a security agent of Latortue's,

Leon Leblanc, of attempting to assassinate him in March, 2004.”

One of Sanderson’s most enlightening cables

is

that of Nov. 20, 2006. It is based on a Nov. 9 meeting that

one of Youri’s close associates (whose name has been removed

from this report and the cable posted on WikiLeaks’ site to

protect him) had with Embassy political officers or “poloffs.”

The colleague “shared with poloffs his concerns regarding

Latortue's illegal or otherwise unsavory activities in the port

city of Gonaïves and other areas of the Artibonite,”

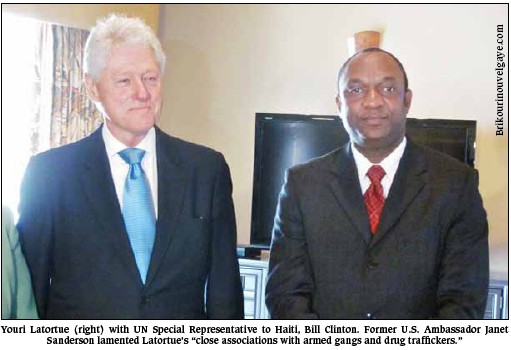

Sanderson wrote. “Latortue's family connections play a part

in his ability to manipulate the region, as do his close

associations with armed gangs and drug traffickers.”

An Ambitious Politician

“The Latortue family is crawling all

over Haitian politics,” the man told the Embassy. “Youri's

sister is the former mayor of Gonaïves, and the former delegate

to the region was a cousin of his as well. The administration

filled Haiti's local and municipal offices by presidential

appointment during the IGoH. Senator Latortue had influence

over these appointments through his relation with IGoH Prime

Minister Gerard Latortue, and managed to place members of his

party in most positions around the Artibonite. The senator used

these people to consolidate his power and influence in the

region until the new delegate to the Artibonite appointed new

local and regional officials who were not in the back pocket of

Senator Latortue.”

The colleague “likened Senator

Latortue's authority in the port city of Gonaïves to that of a

mafia boss,” the cable continued. “He claimed that the

somewhat lethargic port and the drug and other contraband

trafficking taking place there are completely under the

Senator's command. The port in Gonaïves is largely controlled

by the Cannibal Army gang, which faces persistent competition

from two other gangs, Des Cahos and Jubile Blan. Senator

Latortue exerts influence over all three groups and is thus able

to maintain sway over dealings in the port. Senator Latortue's

other businesses in Gonaïves include a nightclub and movie

theater, both of questionable legitimacy.”

Sanderson also noted that “an

oft-disruptive popular organization in St. Marc named ‘Bale

Wouze’ recently accused the senator of distributing weapons in

an effort to destabilize the government.” Latortue’s

colleague “phoned the Embassy on November 16 to reinforce the

Bale Wouze accusations, and also to report another incident in

which Senator Latortue and friends were stealing telephone poles

and utility boxes from Port-au-Prince for use in Gonaïves.”

The colleague described how Youri was a savvy politician. “After

the large-scale flooding in the Artibonite in September, the

central government allocated emergency food supplies to be

distributed to the flood victims,” Sanderson wrote, but “Senator

Latortue intercepted the supplies and stashed them temporarily

somewhere in Gonaïves, and then took the supplies to the victims

and acted as if he was personally responsible for the handouts.” |