|

Reprinted from The Nation. This article was reported in

partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute,

with additional support from the Canadian Centre for

Investigative Reporting .

When Demosthene Lubert heard that Bill

Clinton's foundation was going to rebuild his collapsed school

at the epicenter of Haiti's January 12, 2010, earthquake, in the

coastal city of Léogâne, the academic director thought he was "in

paradise."

The project was announced by Clinton as

his foundation's first contribution to the Interim Haiti

Recovery Commission (IHRC), which the former president

co-chairs. The foundation described the project as "hurricane-proof...

emergency shelters that can also serve as schools... to ensure

the safety of vulnerable populations in high risk areas during

the hurricane season," while also providing Haitian

schoolchildren "a decent place to learn" and creating

local jobs. The facilities, according to the foundation, would

be equipped with power generators, restrooms, water and sanitary

storage. They became one of the IHRC's first projects.

However, when Nation reporters

visited the "hurricane-proof" shelters in June, six to

eight months after they'd been installed, we found them to

consist of twenty imported prefab trailers beset by a host of

problems, from mold to sweltering heat to shoddy construction.

Most disturbing, they were manufactured by the same company,

Clayton Homes, that is being sued in the United States for

providing the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) with

formaldehyde-laced trailers in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Air samples collected from twelve Haiti trailers detected

worrying levels of this carcinogen in one, according to

laboratory results obtained as part of a joint investigation by

The Nation and The Nation Institute's Investigative Fund.

Clayton Homes is owned by Berkshire

Hathaway, the holding company run by Warren Buffett, one of the

"notable" private-sector members of the Clinton Global

Initiative, according to the initiative's website. ("Members"

are typically required to pay $20,000 a year to the charity, but

foundation officials would not disclose whether Buffett had made

such a donation.) Buffett was also a prominent Hillary Clinton

supporter during the 2008 presidential race, and he co-hosted a

fundraiser that brought in at least $1 million for her campaign.

By mid-June, two of the four schools where

the Clinton Foundation classrooms were installed had prematurely

ended classes for the summer because the temperature in the

trailers frequently exceeded 100 degrees, and one had yet to

open for lack of water and sanitation facilities.

As Judith Seide, a student in Lubert's

sixth-grade class, explained to The Nation, she and her

classmates regularly suffer from painful headaches in their new

Clinton Foundation classroom. Every day, she said, her "head

hurts and I feel it spinning and have to stop moving, otherwise

I'd fall." Her vision goes dark, as is the case with her

classmate Judel, who sometimes can't open his eyes because, said

Seide, "he's allergic to the heat." Their teacher

regularly relocates the class outside into the shade of the

trailer because the swelter inside is insufferable.

Sitting in the sixth-grade classroom,

student Mondialie Cinéas, who dreams of becoming a nurse, said

that three times a week the teacher gives her and her classmates

painkillers so that they can make it through the school day. "At

noon, the class gets so hot, kids get headaches," the

12-year-old said, wiping beads of sweat from her brow. She is

worried because "the kids feel sick, can't work, can't

advance to succeed."

Word about the students' headaches has

made it all the way to the Léogâne mayor's office, but like the

students, their teachers and parents, Mayor Santos Alexis

chalked it up to the intense heat inside the trailers.

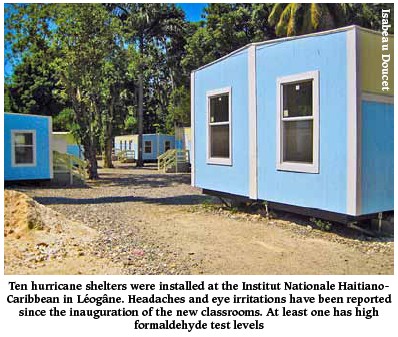

But headaches were not the only health

problems students, staff and parents at the Institut Haitiano-Caribbean

(INHAC) told us they've suffered from since the inauguration of

the classrooms. Innocent Sylvain, a shy janitor who looks much

older than his 41 years, spends more time than anyone in the new

trailer classrooms, with the inglorious task of mopping up the

water that leaks through the doors and windows each time it

rains. He has felt a burning sensation in his eyes ever since he

began working long hours in the trailers. One of his eyes is

completely bloodshot, and he said, "They itch and burn."

He'd previously been sensitive to eye irritation, but he says

he's had worse "problems since the month of January"—when

the schoolrooms opened their doors.

Any number of factors might be contributing

to the headaches and eye irritation reported by INHAC staff and

students. However, similar symptoms were experienced by those

living in the FEMA trailers that were found by the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention to have unsafe levels of

formaldehyde. Lab tests conducted as part of our investigation

in Haiti discovered levels of the carcinogen in the sixth-grade

Clinton Foundation classroom in Léogâne at 250 parts per

billion—two and a half times the level at which the CDC warned

FEMA trailer residents that sensitive people, such as children,

could face adverse health effects. Assay Technologies, the

accredited lab that analyzed the air tests, identifies 100 parts

per billion and more as the level at which "65–80% of the

population will most likely exhibit some adverse health

symptoms... when exposed continually over extended periods of

time."

Randy Maddalena, a scientist specializing

in indoor pollutants at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory,

characterized the 250 parts per billion finding as "a very

high level" of formaldehyde and warned that "it's of

concern," particularly given the small sample size. An

elevated level of formaldehyde in one of twelve trailers tested

is comparable to the formaldehyde emissions problems detected in

about 9% of similar Clayton mobile homes supplied by FEMA after

Hurricane Katrina. Maddalena explained that in "normal"

buildings, you'll see rates 12 to 25 times lower than 250 parts

per billion, "and even that's considered above regulatory

thresholds."

According to the CDC, formaldehyde exposure

can exacerbate symptoms of asthma and has been linked to chronic

lung disease. Studies have shown that children are particularly

vulnerable to its respiratory effects. The chemical was recently

added to the US Department of Health and Human Services' "Report

of Carcinogens," based on studies linking exposure to

formaldehyde with increased risk for rare types of cancer.

"You should get those kids outta there,"

Maddalena said. The scientist emphasized that Haiti's hot and

humid climate could well be contributing to high emissions of

the carcinogen in the classroom. Indeed, months before the

launch of the Clinton trailer project, the nation's climate was

widely cited as a key problem with a trailer industry proposal

to ship FEMA trailers to Haiti for shelter after the earthquake.

The proposal was ultimately rejected by FEMA, following a

critical letter from Bennie Thompson, chair of the House

Committee on Homeland Security, who argued, "This country's

immediate response to help in this humanitarian crisis should

not be blemished by later concerns over adverse health

consequences precipitated by our efforts."

Yet several months later, the Knoxville

News Sentinel reported that Clayton Homes had been awarded a

million-dollar contract to ship 20 trailers to Haiti, for use as

classrooms for schoolchildren. The Clinton Foundation claims it

went through a bidding process before awarding the contract to

Clayton Homes, which was already embroiled in the FEMA trailer

lawsuit. But despite repeated requests, the foundation has not

provided The Nation with any documentation of this

process.

There are hints that Clayton Homes

aggressively pursued the contract. For example, a company press

release dated Aug. 6, 2010, notes, "When former President

Bill Clinton was named to head the relief effort, Clayton's

Director of International Development, Paul Thomas, called the

Clinton Foundation to see if there was a way to help."

The chief of staff for the office of the

UN Special Envoy, Garry Conille, emphasized that the

foundation's decision-making on the project took place in a

context of great urgency, with the advent of the 2010 hurricane

season, when 1.5 million people were living in tent camps. "Under

the circumstances, with all these people exposed, with the first

rains," said Conille, "it would have been completely

acceptable to go to a single source, but we didn't."

The Clinton Foundation's chief

operating officer, Laura Graham, said in a phone interview that

the contract was awarded to Clayton on the basis of a "limited

request for proposals" from nine companies. She added that

the decision was informed by "recommendations from a panel

including a lot of these experts that do this work for a living,

and Clayton was recommended as the most cost-efficient, with the

best product and with the strongest Haitian partner." She

clarified that she did not participate in the bidding process

but said there were "representatives from the foundation as

well as [the UN] Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian

Affairs [OCHA], the UN Special Envoy Office and the

International Organization for Migration [IOM]...and there was a

request for proposals run by them."

When asked to comment on that claim,

Bradley Mellicker, IOM's Port-au-Prince–based emergency

preparedness and response officer, said, "That's a lie. The

Clinton Foundation paid for the containers through a no-bid

process." Imogen Wall, former spokeswoman for OCHA in Haiti,

responded by e-mail that OCHA never deals with procurement or

project management.

The Nation made multiple attempts to

reach Bill Clinton for comment. However, the former president,

known for championing the role of nonprofits in global affairs

("Unlike the government, we don't have to be quite as worried

about a bad story in the newspapers," he recently said in a

speech), never responded. A Clayton Homes official referred all

queries regarding the contract to the Clinton Foundation.

When he heard that the new classrooms in

his community had been built by a FEMA formaldehyde litigation

defendant, Santos Alexis, Léogâne's stately mayor, said, "I

hope these are not the same trailers that made people sick in

the US. Otherwise I would be very critical; it would be chaos."

(They are indeed different trailers, according to an engineer at

Clayton Homes, who said the new classrooms were constructed

specifically for the Clinton Foundation's Haiti project.)

"It would be humiliating to us, and

we'll take this as a black thing," the mayor added, drawing

a parallel between his community in Haiti, the world's first

black republic, and the disproportionate numbers of

African-Americans affected by the US government's mismanagement

of the emergency response after Hurricane Katrina.

Demosthene Lubert's disappointment is

palpable as he sits in one of his new-smelling classrooms,

perspiration dripping from his face. He had envisioned that the

foundation of the former US president would rebuild INHAC, his

school, as a modern institution with solar panel–powered lights

and Wi-Fi. At a meeting of the Clinton Global Initiative in May,

Dr. Paul Farmer, Clinton's deputy UN special envoy, called for

healthcare to be integrated into schools. At the very least,

Lubert expected the Clinton Foundation, which is active in

global health philanthropy and cholera prevention in Haiti, to

help with school sanitation.

"I thought the grand foundation of

Clinton was going to build us latrines and dig us wells for the

children to wash their hands before meals and after using the

toilet... especially as we're at the mercy of cholera,"

Lubert says with a sigh. Less than an hour east of Léogâne, in

Carrefour, the number of cholera cases went from 85 per week at

the end of April to 820 a week at the beginning of June,

according to Sylvain Groulx, country director of Médecins Sans

Frontières. The disease, which is preventable with proper

sanitary conditions, has killed 5,500 people since the epidemic

began last October.

The Clinton Foundation did not build so

much as a latrine at the school, or at any of the three other

schools where its trailers were installed. (INHAC and two of the

other schools had a limited number of pre-existing outhouses,

which the school directors saw as inadequate, while the fourth

did not have a single outhouse, making it unusable, according to

the school's director.)

Conille, Clinton's chief of staff at his UN

office, acknowledged in a telephone interview that the trailer

classrooms "would never meet the standards for school

building" under Haitian or international regulations.

"Normally when you hear 'Clin-ton,' when

people speak of 'Clin-ton,' the name 'Clin-ton' carries a lot of

weight," says Lubert. He trails off, looking suddenly

uncertain. Clinton's name echoes ambiguously through the swampy

chemical air like a plea, a mantra or a brand.

Jun. 1 marked the beginning of Haiti's 2011

hurricane season, and meteorologists project that Haiti could

face up to 18 tropical storms with three to six of these

developing to hurricane strength. Léogâne, where 95% of the

downtown area was flooded by Hurricane Tomas last year, is

relying on the Clinton Foundation's trailers as Plan A in the

municipality's emergency response.

The foundation's original proposal to the

IHRC referred to the buildings it planned to construct in

Léogâne as "hurricane-proof" shelters, and this past

March, Clinton Foundation foreign policy director Ami Desai

reiterated that claim in a phone interview. On the foundation

website, the promotional write-up about the trailers is featured

under the heading "Emergency Hurricane Shelter Project."

Larry Tanner, a wind science

specialist at Texas Tech University, was "suspicious"

when he heard that trailers were to be used as hurricane

shelters in Haiti. Tanner thought it unlikely that Clayton Homes

had developed a mobile home that could safely be used as a

hurricane shelter, saying in a telephone interview that he put

the odds at "slim to none." Mobile homes are considered

by FEMA to be so unsafe in hurricanes that the agency

unequivocally advises the public to evacuate them.

In an interview with The Nation,

Clayton Homes engineer Mark Izzo said the Léogâne trailers could

withstand winds of up to 140 miles per hour. The company arrived

at this figure through calculations, he said, rather than

testing.

But Tanner emphasizes that such structures

must be rigorously tested for resistance to high winds and

projectiles. Clayton Homes's failure to test the trailers meant

that they would not meet the international construction standard

for hurricane shelter. "It certainly would not be accepted by

FEMA either," Tanner added. Moreover, the kind of anchoring

systems used by the trailers in Léogâne — which rely on metal

straps to attach the shelter to the ground — "fail routinely,"

according to Tanner.

Two weeks into Haiti's hurricane season,

The Nation visited some of the Clinton shelters with Kit

Miyamoto, a California-based structural engineer contracted by

USAID and the Haitian government to assess the safety of

buildings in Port-au-Prince. Standing in front of one of the

trailers, Miyamoto looked doubtful when asked whether, in his

professional view, these structures were, as the Clinton

Foundation has repeatedly claimed, "hurricane-proof." In

the world of engineering, buildings are rarely considered to be

truly hurricane-proof, explained Miyamoto, who said he had never

heard of a wooden trailer being used as a hurricane shelter, let

alone being referred to as a hurricane-proof building. "To be

hurricane-proof you a need a heavier structure with concrete or

blocks," he explained.

Miyamoto emphasized that one of the most

crucial elements for the public safety was how well the

shelters' limitations were explained to the community expected

to use them. "Hopefully people do understand that these

windows do need to be protected if a major hurricane is expected

to be coming," he said. Miyamoto said the likelihood is "really

high" that the windows will break without storm shutters,

and "once those window systems break," he explained,

making a toppling motion with his arms, "you cannot just be

in there." The roof will "pop off."

When asked if the shelters had come with

any storm shutters, André Hercule, director of Saint Thérèse de

Darbonne elementary school, which has also received Clinton

trailers, shook his head, then grabbed the nearest open trailer

window and effortlessly slid it shut. Clicking it locked, he

explained, "We'd close all the windows." The school

director remains confident after hearing Clinton speak at a news

conference in August 2010 at his school that the trailers are

hurricane-proof.

Léogâne's Department of Civil Protection

may also be operating on this assumption. At the Léogâne town

hall, a derelict white paint-chipped building that looks stately

in contrast to the 17-month-old tent camp nearby, DCP

coordinator Philippe Joseph explained the municipality's plans

for community outreach in the event of a hurricane. "We'll

send scouts with megaphones and tell people to gather their

papers and go to the Clinton Foundation shelters," he said

as he sketched a rough map, indicating the best routes to the

dual-purpose school buildings from the geographic zones most

vulnerable to storms.

Asked if he believed the trailers would

offer adequate protection during a hurricane, Joseph seemed

taken aback: Clinton had himself said that these were

hurricane-proof shelters, he said.

In a jungly field on the outskirts of

Léogâne, four of the 20 Clinton classrooms sit empty at another

school, Coeur de Jesus. Because of the trailers' leaky roofs,

puddles form on the floor that need to be mopped up by the

maintenance staff. As school director Antoine Beauvais

explained, the new 16-by-40-foot trailers were too bulky to fit

in the cramped residential area where his school was previously

located. But for lack of toilet facilities or running water

provided by the foundation for the newly created remote campus,

the school has been unable to use its new trailer classrooms.

When The Nation visited the site

with Miyamoto, at least one strap on a trailer slated to be used

as a hurricane shelter in the coming months was already loose.

As Miyamoto moved the slack metal ribbon that is meant to ensure

the trailer stays stable during a storm, the structural engineer

remarked that these kinds of anchoring systems are liable to

corrode. "You definitely want to look at it at least once a

year," he said grimly.

It's unclear whether such maintenance will

occur. Clayton Homes recently visited some of the schools after

the IOM, which works with the UN, raised concerns about the

condition of the shelters. However, Conille said he did not know

anything about plans the Clinton Foundation had made for the

maintenance of the "hurricane shelters" in the longer

term. The Haitian contractor who was initially hired to help

install the shelters, Philippe Cinéas of AC Construction, said

that neither he nor his staff were trained to service them. This

raised concerns for Cinéas because, as he knew from experience,

"in Haiti maintenance is always a problem."

While Clinton Foundation COO Laura Graham

claims that the foundation has always been "very accessible"

to the school and municipal officials in Léogâne, neither the

school directors nor the civil protection coordinator had any

way of getting in touch with the foundation, they told The

Nation, and had to resort to going through intermediaries.

Joseph, the DCP chief for Léogâne, faults

the trailer project for being decided from afar and "from the

top down," like so much of Haiti relief. While the Clinton

Foundation claims that it worked with local government to

implement the shelter plan, Joseph disputes this. The foundation

simply informed him that it was building four schools in his

district, he says. "To me this is not a consultation,"

the local official remarked. "To consult people you have to

ask them what they need and how they think it could best be

implemented."

Joseph ascribes the new shelters' "infernal"

heat, humidity and other problems to this lack of on-the-ground

consultation. He added, with regret, that people in desperate

need of employment and shelters watched as "the Clinton

Foundation came in with all its specialists and equipment, but

they didn't give any training." He said that "if they use

a local firm they will not only create jobs in a community that

has been decapitalized by the quake but they will also take into

account the environmental reality on the ground."

In the proposal approved by the IHRC, the

Clinton Foundation said that "up to 300 local workers would

be employed to build the schools." Cinéas said there were

only five to eight people hired by his firm on a very temporary

basis, and the foundation declined to comment on what additional

jobs were created.

Farmer, the Clinton envoy, recently

published a report on trends in Haiti's dysfunctional aid

system. He stressed the need for "accompaniment" to be

the guiding principle of Haiti's reconstruction, with Haitians "in

the driver's seat" and the international community listening

to their priorities. Farmer also emphasized the importance of

local procurement and job creation.

It is hard to imagine a better case study

of the very opposite approach than the Clinton trailers. In

response to questions about what due diligence the foundation

did to ensure the safety of the trailers it purchased for use as

hurricane shelters, the Clinton Foundation initially insisted

that the most appropriate person to speak to was a Haitian

employee of Clinton's UN Office. When Graham, the foundation's

COO, finally agreed to talk about the project on the record, she

denied that the foundation had been responsible for any due

diligence regarding its own project, claiming that those

responsible were a "panel of experts," including one

point person from the foundation, Greg Milne, and

representatives of other organizations. (Milne referred all

questions to the foundation's press office.) The Clinton

Foundation agreed to furnish documentation of who was on this

panel but by press time had not done so.

Graham said that the staff of the Clinton

Foundation — which has for more than a year publicized the "hurricane

shelters" that "President Clinton" built in Léogâne —

are "not experts" in hurricane shelter construction. She

claimed the same "panel of experts" would have been

responsible for due diligence to ensure air quality of the

shelters whose secondary purpose was as classrooms.

Explaining Bill Clinton's rationale for the

trailers, which were installed at the tail end of the 2010

hurricane season, Conille said, "It was not meant to be

sustainable. It was meant because we didn't want to have dead

people in September." According to Conille, Clinton was

deeply troubled by what would happen to the women and children

in case of a serious storm — and as the former president felt

that "no one" was doing anything about the issue, he took

the lead himself. Moreover, Clinton didn't want to have his new

"hurricane shelters" sitting empty while schoolchildren

had classes in tents, Conille added.

Yet according to Maddalena, given the high

rate of formaldehyde found in one of the classrooms, and the

children's headaches, "they'd be better off studying outside

under a tarp."

Wall, the former OCHA spokeswoman,

responded by e-mail, "We all knew that that project was

misconceived from the start, a classic example of aid designed

from a distance with no understanding of ground level realities

or needs. It has had a predictably long and unhappy history from

the start."

Even Conille largely concurred, in a

telephone interview, that there were many problems with the

project, saying, "It made sense at that time, and I guess

someone could argue it wasn't the best idea in retrospect."

For his part, Léogâne Mayor Santos Alexis says he is still

waiting for Bill Clinton to follow through on his pledge to

equip Léogâne with hurricane-proof school buildings. Asked about

his view on the Clinton Foundation's claims to having completed

an "Emergency Hurricane Shelter Project" replete with new

classrooms for his town, Alexis is defiant. "If those at the

Clinton Foundation are sure it's done then they should prove it,

they should show it to us, because I know nothing about it,"

he remarked coyly, gazing out from behind his shades. Seated at

his desk in a crumbling municipal building, the mayor said he is

still waiting for the real Clinton Foundation schools, "built

with norms that protect people from hurricanes and flooding." |