|

United Nations forces occupying Haiti were

poorly trained, spied on student groups, impaired elections, and

recklessly shot, killed and wounded hundreds of civilians,

according to secret U.S. diplomatic cables.

In one “astonishing”

case, according to the cables, UN troops fired 28,000 rounds in

just one month in a neighborhood of Port-au-Prince known for

resisting the UN occupation and the February 2004 coup that

ousted democratically elected president Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

“Civilian casualties [from

UN forays] in Cité Soleil … [rose] from 100 wounded in October

[2005] to between 170 and 205 in December [2005],” wrote

then Chargé d’Affaires Timothy M. Carney in a secret Jan. 19,

2006, cable. “Half of these are women and children.

Assertions that all were used as human shields strain credulity.”

Just six months prior, acting

under intense U.S. and Haitian elite pressure, 1,400 UN troops

sealed off the pro-Aristide slum, firing 22,000 rounds and

causing dozens of casualties in just one six-hour night-time

raid on Jul. 6. UN troops continued their attacks throughout the

year, at one point firing an average of 2,000 rounds a day, one

UN official told a reporter.

The controversial 12,000-strong

UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) intervened in the

Caribbean country in the wake of the bloody February 2004 coup

that ousted Aristide. But the mission, with an annual cost of

more than $850 million, is up for renewal before the UN Security

Council next month and Haitian and international opposition is

widespread and growing.

Several scientific studies have

established that Nepalese UN troops brought a deadly cholera

epidemic to Haiti. UN leadership tried to deny that charge,

which surfaced almost simultaneously with the disease last

October.

In recent weeks, anti-UN

sentiment has exploded in response to a video showing Uruguayan

troops apparently sexually assaulting a young man in the

southern town of Port Salut. This follows the expulsion of 111

Sri Lankan soldiers for sexual exploitation and the abuse of

under-aged minors in November 2007. “Among those repatriated

are the battalion's second-in-command and two company commanders

at the rank of major,” noted one secret 2006 cable.

Furthermore, new information

has emerged around the case of a teenager found hung in a UN

base in Haiti’s northern city of Cap Haïtien (see

accompanying

article by Ansel Herz).

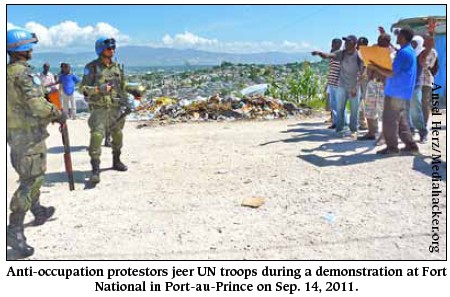

Events like these have sparked

deep anger toward MINUSTAH, which, since its Jun. 1, 2004

deployment, has repeatedly faced the fierce nationalism that

imbues Latin America’s first independent republic.

To counter this local

opposition, the UN set up to its own intelligence apparatus, the

Joint Mission Analysis Cell (JMAC), with a “network of paid

informants” to spy on groups it felt were a threat,

according to a Sep. 15, 2006 cable. A cable three months later

explained that “MINUSTAH had focused over the past several

weeks on attempting to identify elements among [a student] group

that posed a threat to its mandate.”

The secret cables describe

repeated clashes between Haitians and UN forces, many of which

ended in deaths. A Dec. 26, 2006 cable describes one notorious

UN incursion into Cité Soleil four days earlier, when, according

to the Haiti Action Committe (HAC), 400 UN troops attacked the

shantytown with armored vehicles at around 3 a.m. in a battle

that raged for the rest of the day. “Initial press accounts

reported at least 40 casualties, all civilians,” HAC

reported. “According to community testimony, UN forces flew

overhead in helicopters and fired down into houses while other

troops attacked from the ground with Armored Personnel Carriers

(APCs). People were killed in their homes. UN troops from

Brazil, Chile, Uruguay and Bolivia took part in the all-day

siege, backed by Haitian police.”

The Haitian Press Agency (AHP)

reported that “local residents say the victims were ordinary

citizens whose only crime was that they live in the targeted

neighborhood” and that “residents were outraged that [UN]

soldiers refused to allow medical care... for people they had

injured” by blocking Red Cross vehicles from coming to aid

the wounded.

So-called gang leader “Belony’s

brother and eight other Belony loyalists were killed during the

[UN] operation, with one other gang member injured,” the

Dec. 26 cable reported, adding that “according to [the

conservative] Radio Métropole, 30 residents were wounded during

the confrontation.”

The same cable also reveals

that the UN was at war, not just with “gangs” (its

moniker for pro-Lavalas groups) but with Cité Soleil’s

citizenry. “The primary objectives and targets were not

reached because a number of large rocks that were placed along

the route Impasse Chavanne which leads to Belony’s home,”

Chargé d’Affaires Thomas C. Tighe wrote. “The Brazilian

battalion removed the boulders shortly before the operation

began but the community replaced them within five minutes.”

Tighe further explains that

MINUSTAH soldiers were so scared and trigger-happy that at one

point during the operation Chinese UN troops “ fired on the

Brazilian battalion. The incident is under investigation.”

The UN publicly called the

operation a success, but JMAC’s deputy director told the U.S.

Embassy privately that it was “a bit of a flop.”

“JMAC informants indicated

that gangs were holding as many as 40 kidnapping victims in the

targeted buildings,” noted the cables, but not a single

alleged kidnapping victim was found.

In a Mar. 23, 2005 cable, U.S.

Ambassador James Foley argued that “MINUSTAH needs to quickly

and decisively respond to threats from both the armed rebels and

pro-Aristide criminal/political gangs,” but recognized in

the same dispatch that “after two days of pro-active engagement, Haitians are criticizing the

peacekeepers as over-aggressive.”

Outgoing President René Préval

sharply criticized the UN role in April, saying, "Tanks,

armed vehicles and soldiers should have given way to bulldozers,

engineers, more police instructors and experts on reforming the

judicial and prison systems.”

New right-wing President Michel

Martelly, who succeeded Préval in May, has invited the UN troops

to stay. However, he is seeking to channel anti-MINUSTAH outrage

into support for his bid to restore Haiti’s disbanded army, a

move strongly opposed by many Haitians.

Other key actors, including

Brazil’s military leadership, are looking to exit, however

gradually. New Brazilian Defense Minister, Celso Amorim said

that “he supports the withdrawal of Brazilian troops from

Haiti,” but has proposed a time-table lasting until 2015.

But the main driver behind

MINUSTAH is Washington, the secret cables show.

U.S. Ambassador Janet Sanderson

insisted in an Oct. 1, 2008 cable that MINUSTAH has been “an

indispensable tool in realizing core USG [U.S. Government]

policy interests in Haiti.” The UN is establishing “domestic

security and political stability” there, she wrote, all

necessary to prevent the resurgence of “populist and

anti-market economy political forces” and an “exodus of

seaborne migrants.”

“In the current context of

our military commitments elsewhere, the U.S. alone could not

replace this mission,” Sanderson concluded.

Furthermore, a February 2006

General Accounting Office report estimated “that it would

cost the United States about twice as much as the United

Nations... to conduct a peacekeeping operation similar to

the...’MINUSTAH’. The UN budgeted $428 million for the first 14

months of this mission. A U.S. operation in Haiti of the same

size and duration would cost an estimated $876 million, far

exceeding the U.S. contribution for MINUSTAH of $116 million.”

The 2004 Security Council

resolution establishing MINUSTAH called for it to ensure a “secure

and stable environment,” reconstruct Haiti’s police force,

engage in a comprehensive Disarmament, Demobilization and

Reintegration (DDR) program, organize elections, and protect

human rights.

But the 1,918 secret U.S. State

Department Haiti cables released by the anti-secrecy group

Wikileaks describe an extraordinary litany of failures and

manipulation of the mission, the third largest UN military force

anywhere in the world.

The key goal of the U.S. and UN

mission has been to rebuild the Haitian National Police (HNP),

which Foley complained Aristide had “undermined... by placing

criminal gang members [i.e. pro-Lavalas popular organization

militants] directly into their ranks,” in a May 3, 2005

cable. But seven years later, the force has been, if anything,

debilitated due precisely to its anti-Lavalas politicization,

the integration of coup-making former soldiers, and the

ham-fisted meddling of the UN and U.S. Embassy.

“The HNP is an example of

the international community's failure to work in concert,”

MINUSTAH’s then chief, Edmond Mulet, was quoted in an Aug. 2,

2006 cable. “Each donor country has pushed its own policing

model and donor efforts contradicted one another.”

“The HNP continues to suffer

from corruption among its ranks, a broken system of justice,

substandard command and supervisory control, inadequate levels

of training, and scant equipment resources,” noted another

secret cable from May 6, 2005, a description that is equally

applicable today.

As for the DDR program, its

Chief Desmond Molloy said that he set a target of 10,000 DDR

participants when the program launched in October 2004. “He

lowered his expectations to a hopeful 2000 by June 2006, but

would be happy with 500,” said one secret cable in January

2006.

When the DDR supposedly

demobilized 300 former soldiers in Cap Haïtien, it collected a

mere “seven dilapidated weapons included six M-14's and 1

sub-machine gun,” a Mar. 15, 2005 cable by Ambassador James

Foley explains.

The cables also slam the UN “mismanagement”

of elections, saying the UN mission’s “overall lack of

elections administration experience or expertise has crippled

MINUSTAH's ability to prepare for elections.”

Still, the U.S. pushed ahead

with exclusionary 2006 presidential elections in Haiti so that

Latin American countries could have political cover to send

troops, the cables show.

“[T]he important thing was

to have elections, noting that it would be difficult for

countries contributing to MINUSTAH to maintain their presence

without elections,” said then Assistant Secretary of State

Thomas Shannon to a European counterpart in a wide ranging 2006

meeting on Latin American issues.

Despite this charade, there

were growing concerns in Latin American governments about

MINUSTAH’s sovereignty-trampling role, the cables show.

“Bolivia's energy minister

published an article in November 2006 calling MINUSTAH a ‘U.S.

occupation force,’” noted an Apr. 20, 2007 cable. “Later,

President Evo Morales suggested prohibiting war in Bolivia's

constitution and asked if a country with such aspirations should

contribute to MINUSTAH.”

In response to the “anti-MINUSTAH

news reports from La Paz,” the UN organized a high-level

delegation from Bolivia, led by the Defense Minister, to visit

Port-au-Prince, where they were suitably “impressed by the UN

operations.”

“The important contribution

of Latin American countries to the UN force here cannot be

overstated,” concluded the cable’s author, Deputy Chief of

Mission Thomas Tighe.

Both Haiti’s 2006 and 2010

presidential ballots, largely carried out by the UN, took place

without the participation of Haiti’s most popular political

party, Fanmi Lavalas (FL), led by Aristide, who was in a U.S.

and UN imposed exile at the time of both polls.

“In terms of the

construction of a democratic climate and tradition, we have

regressed in comparison with the periods preceding MINUSTAH’s

arrival,” said Haitian economist Camille Chalmers, the

Executive Director of the Haitian Platform to Advocate for

Alternative Development (PAPDA), echoing a common refrain that

the elections are more about the needs and interests of the U.S.

rather than the Haitian people.

The UN’s human rights record is

equally dismal. Apart from their direct military attacks on

pro-democracy Haitians, like those described in Cité Soleil, UN

troops “effectively provided cover for the police to wage a

campaign of terror in Port-au-Prince’s slums,” said a 2005

report by the Harvard Law Students Advocates for Human Rights.

MINUSTAH, the HNP, and

paramilitary forces supported by the Haitian business elite

killed an estimated 3,000 people and jailed thousands of coup

opponents and Fanmi Lavalas supporters during the consolidation

of the February 2004 coup until mid-2007.

U.S. Embassy Chargé d’Affaires

Timothy Carney only said, “[T]here has been no tangible UN

contribution to improving the human rights situation,” in a

January 4, 2006 cable. (Ironically, that same day, in a meeting

with Haitian business leaders, Carney supported a proposal for

UN troops to attack armed groups in Cité Soleil,

Haiti’s largest slum, fully foreseeing that there would be “unintended

civilian casualties,” as he wrote in a secret cable two days

later.)

Notwithstanding this record of

failure and repression, the UN, acting on behalf of Washington

and Paris, still seeks to extend its authority in Haiti. While

paying lip-service to the “views” of the elected Haitian

government, UN officials sought to unilaterally decide how to

deploy their forces and when to renew their Security Council

mandate to occupy Haiti, the cables reveal.

MINUSTAH critics charge the

occupation violates the UN Charter’s Chapter 7 which specifies

that “action by air, sea, or land forces” should be used

only “to maintain or restore international peace and

security,” that is, conflicts between states, not the case

in Haiti. It also violates Haiti’s Constitution which explicitly

states in Article 263-1: “No other armed corps may exist in

the national territory,” other that the Haitian police and

army, the latter presently demobilized.

In a Jun. 2, 2006 cable former

U.S. Ambassador to the UN John Bolton explains how Wolfgang Weisbrod-Weber, the Director of the UN’s Department of

Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) Europe and Latin America

Division, opposed changing, reducing or ending MINUSTAH’s

mission, as some had proposed, once an elected government was in

place in May 2006.

Instead Weisbrod-Weber “reported

that the mission's military component and its Joint Mission

Analysis Cell (JMAC) believe that current force levels should be

maintained after the expiration of the current mandate” on

Aug. 15, 2006, Bolton wrote. Furthermore, he “did not endorse

calls for an expanded mandate for MINUSTAH in development,”

the cable notes, “despite Préval's inaugural address call for

‘more tractors and fewer tanks.’” Bolton also noted that “Brazil

and France strongly supported DPKO on the need to maintain

MINUSTAH's force levels after August 15.”

Not only did Weisbord-Weber

believe that “Haiti will only be able to assume

responsibility for its own security when its rule of law

institutions are reformed,” he even proposed expanding

oversight, arguing that “MINUSTAH must be able to monitor and

accompany legal cases as they pass through every stage of the

Haitian judiciary,” a judiciary whose prosecution the UN was

immune from, despite its regular criminal acts, due to an

agreement with the illegitimate post-coup de facto regime

of Gérard Latortue.

Perhaps more than any other

single issue, it is the cholera epidemic, whose origin has been

tied to the poor sanitary practices at a UN base, that has led

to today’s anti-UN uprising. Throughout Haiti, graffiti

proclaims “UN=Kolera.” The epidemic has already killed

over 6,100 Haitians and infected 400,000 others. But the cables

show that UN sanitation standards were already an issue over two

years ago.

“Construction of roads and

drainage canals at the [U.S.-funded and run Police] Academy has

been impacted by MINUSTAH's inappropriate management of human

waste at the Jordanian camp on the Academy grounds,” noted a

Jan. 7, 2009, cable.

The outrage over cholera’s

introduction into Haiti has now merged with that over the images

of five Uruguayan UN soldiers apparently sexually assaulting a

Haitian man in July. The victim and his family began pursuing

legal action against the troops, but they were almost

immediately spirited out of the country, another affront to

Haiti’s “rule of law institutions,” which the UN purports

to defend.

As the Oct. 15 renewal

of MINUSTAH’s mandate in the UN Security Council looms, Haitian

disgust with and rejection of the force is reaching a fever

pitch. UNASUR Defense Ministers met on Sep. 8 and recognized the

need for withdrawal. And among Haitians, even among those who

once supported the UN mission, support is falling away.

“I'm not one those anti-UN

people,” wrote Boston-based Haitian blogger Reginald

Toussaint in May. “I like the idea of a United Nations and,

for the most part, I think they do good work... However, in the

case of Haiti, they are causing more harm than good.”

One of the most compelling

cases against the UN occupation was made in a long Aug. 15

article by Haitian columnist Dady Chéry on the Axis of Logic

website. Among the “Top Ten” reasons for the UN to leave

Haiti, she lists: “MINUSTAH continually harasses and

humiliates Haitians.... Common criminals in MINUSTAH enjoy

immunity from prosecution... MINUSTAH subverts democracy....

MINUSTAH interferes in Haiti’s political affairs...” and “MINUSTAH

has operated as a large anti-Aristide gang.”

She concludes by writing: “One is tempted to ask

why South American states, with presumably leftist and

nationalistic governments, like

Bolivia and Ecuador, support the occupation of Haiti. After all,

Cuba and Venezuela have amply demonstrated how much more can be

achieved by contributing medical doctors and public-health

workers, instead of soldiers, to Haiti... It is better to show

the remaining MINUSTAH members the door and advise they not slam

it on their way out.” |