|

“None so fitted to break the chains as

they who wear them. None so well equipped to decide what is a

fetter.” - James Connolly

Enslavement by the Enlightened in

Revolutionary Times

In 1789, the year of the French Revolution,

Saint Domingue (now Haiti) was the richest colony in the world.

The source of this wealth was the exploitation of half a million

black slaves who furnished the labor for the sugar, indigo,

cotton, cocoa, and tobacco extracted from over 2,000

plantations.

In principle, a series of royal

edicts called the code noir (slave code) regulated the

conduct of the white slave owners in France’s colonies. The

code noir sanctioned corporal punishment, among other

things, but in practice even this code’s few admonitions to

feed, clothe, and refrain from raping one’s slaves went

unenforced, and the plantation owners did as they wished. In

fact many worked their slaves to death, since it was usually

cheaper to buy than raise a slave. Hence the common proverb of

colonialists of those days: “The Ivory Coast is a good

mother.”

As a result of such

barbarism and the enthusiasm for expanding the slave work force,

although the first slave ships arrived at the island in 1510,

even as late as 1789 two-thirds of the slaves in Saint Domingue

were African-born.

Many thousands of black souls,

some of whom had been warriors sold into slavery, disappeared

into Haiti’s forests immediately on arrival to form communities

of “negres marons” (escaped slaves).

About 28,000 free blacks and

mulattoes also lived in Saint Domingue at the time of the French

Revolution, and most of them owned slaves. These property owners

quickly became interested in what new rights they might extract

from the Revolution because, compared to the French, their

rights were radically curtailed.

As the spirit of the

Enlightenment inflamed everyone, the Haitian slaves would prove

to be those most faithful to its ideals.

The

Non-Violent Route: Struggle for Representation in the French

National Assembly The

Non-Violent Route: Struggle for Representation in the French

National Assembly

Representatives of two groups went to

France to request representation in the French National

Assembly.

Black slaves. Not being permitted to

represent themselves, the black slaves were represented by “the

Society of the Friends of the Blacks.” This society

initially promoted the abolition of slavery and wrote countless

pamphlets opposing slavery and the slave trade. In the end,

however, when it was accused of promoting a slave insurrection,

the society denied that it had ever wanted to abolish slavery

and defended itself by arguing that all it had ever wanted was

to abolish new importation of Africans to the French colonies.

So much for friendship.

Mulatto slave owners. The ultimate

ambition of this group was to become white slave owners. Vincent

Ogé, a wealthy planter and leader of the mulatto slave owners,

presented his clan’s views to the white planter delegates.

Unsatisfied with that meeting, in October 1790 he took part in a

rebellion involving 350 mulattoes. The rebellion was squelched

and Ogé was executed, but on May 15, 1791, the National Assembly

granted rights to “all free blacks and mulattoes who were

born of free mothers and fathers,” in a decision so

qualified that it affected only a few hundred people.

White plantation owners. The white

planters began to grumble about taxation without representation

and the possible advantages of independence. They refused to

abide by the National Assembly’s ruling and concluded that this

decision was the beginning of a move toward the emancipation of

the slaves.

The

Slave Revolt The

Slave Revolt

On August 22, 1791, Saint Domingue’s slaves

rose up in what would ultimately become history’s first and only

successful slave revolt. The initial rebellion was led by Vodou

priest and maroon rebel leader Boukman. The slaves murdered

their white masters by every possible means, trashed the towns

and burned down the plantations. The scale of the attack was

such that for three weeks ships could not approach the coast,

and the smoke from the fires obscured day from night.

On September 24, 1791, the

French National Assembly responded to news of the revolt by

rescinding the rights of free blacks and mulattos. The rebel

leaders were caught and publicly tortured to death. Boukman’s

severed head was put on public display. But even as another

iteration of France’s parliament (the “Legislative Assembly”

that replaced the National Assembly in October 1791) voted on

March 28, 1792 to reinstate the political rights of free blacks

and mulattos, and again decide nothing about slavery, the slaves

were regrouping.

L’Ouverture

From the conflicts, a disciplined

leadership emerged in Toussaint Breda, who later earned the name

Toussaint L’Ouverture for being: Toussaint – the one who

raises all souls. L’Ouverture – the one who finds the

crack in the enemy’s defense and shows the way forward.

Toussaint L’Ouverture, born a

slave in Saint Domingue in 1745 and self taught in many things,

including military strategy, would ultimately drive huge

battalions of the armies of Napoleon, the Spanish, and the

British from the island of Hispaniola and guide Haiti to its

independence.

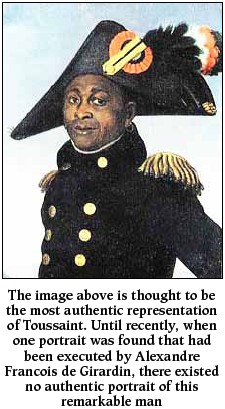

The image above is thought to

be the most authentic representation of Toussaint. Until

recently, when one portrait was found that had been executed by

Alexandre Francois de Girardin, there existed no authentic

portrait of this remarkable man.

Toussaint is thought to have

learned about Africa from his father, who may have been a tribal

chief called Gaou-Guinou. Despite being a slave, Toussaint had

been permitted to learn to read and write, and he taught himself

to read French and Latin. His readings included Julius Caesar’s

military writings. The notions of equality and liberty in the

works of French Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques

Rousseau also resonated well with Toussaint.

On the Breda Plantation,

Toussaint worked as the overseer of livestock, a horticulturist,

horse trainer, and coachman. According to Marcus Rainsford, one

of the earliest chroniclers of the Haitian Revolution:

“Among other traits fondly

preserved in St. Domingo of the conduct of Toussaint during the

early period of his life, are his remarkable benevolence towards

the brute creation, and an unconquerable patience…. He knew how

to avail himself so well of the sagacity of the horse, as to

perform wonders with that animal; without those cruel methods

used to extort from them the docility exhibited in Europe; he

was frequently seen musing amongst the different cattle,

seemingly holding a species of dumb converse, which they

evidently understood, and produced in them undoubted marks of

attention. They knew and manifested their acquaintance, whenever

he appeared…. The only instance in which he could be roused to

irritation, was when a slave had revenged the punishment he

received from his owner upon his harmless and unoffending

cattle.”

Toussaint joined the revolution

about 10 years after being freed from slavery at age 33. Soon

after he took that momentous step, he helped his former master,

M. Bayou de Libertas, escape to Baltimore, Maryland.

Toussaint’s military training

began under the black leader Biassou, but Toussaint was soon

appointed next in command and quickly given his own division.

Initially, he trained a crack team of only a few hundred

extremely well disciplined revolutionaries.

In the fall of 1792, the French

government sent emissaries to Saint Domingue to bring the slave

revolt to heel. In response, Toussaint and the other rebel slave

leaders struck agreements with the British and Spanish to fight

with their armies against the French. If the British and Spanish

merely viewed this as an opportunity to weaken France, so did

the rebels.

By 1793, the French revolution

was being steered by the Jacobins. This group, led by Maximilian

Robespierre, is best known for the Reign of Terror campaign to

rid France of the “enemies of the revolution.”

Though the Jacobins were

ruthless, they were also purists who strived to push the ideals

of revolution as far as they would go. And so it was they who

formally voted to end slavery in the French colonies (including

Haiti) when they took up the issue of equality. Specifically,

after the Haitian slave rebellions and the slave-assisted

invasions from the Spanish and British caused a near total

collapse of Saint Domingue’s economy, the National Convention

(the Jacobin assembly that succeeded the Legislative Assembly)

agreed to hear a multiracial delegation from Saint Domingue

describe the evils of slavery and then voted on February 4, 1794

to end slavery in all the French colonies. Saint Domingue’s

mulattoes opposed this move almost as vigorously as the whites,

who fled Saint Domingue by the thousands. In the end, however,

the slave trade continued because this decree, like so many

others, went unenforced.

Nevertheless, the Haitian slave

rebels felt sufficiently encouraged by the Jacobin vote to offer

to help the French army eject the British and Spanish from the

island. By then Toussaint was leading 4,000 fighters. In January

1798, Haiti’s slave armies, guided by Toussaint’s brilliant

military strategy, defeated the British (an army of 60,000) in

seven major battles over seven days and forced them from the

island. Two years later, the slave army evicted the Spanish army

from the eastern half of Hispaniola (now the Dominican

Republic). By then, Toussaint commanded 55,000 experienced

fighters.

Toussaint L’Ouverture soon

became the de facto ruler of Haiti as the country’s “colonial

governor” and began the even harder tasks of promoting

reconciliation and rebuilding the war-ravaged economy (Compared

to 1789, by 1800 production from the plantations had dropped by

80%.)

According to Rainsford: “Such

was the progress of agriculture from this period, that the

succeeding crop produced (notwithstanding the various

impediments, in addition to the ravages of near a ten years war)

full one third of the quantity of sugar and coffee, which had

ever been produced at its most prosperous period…. Health,

became prevalent throughout the country….”

Haiti’s first Constitution was

written in 1801 under Toussaint’s rule. C. L. R. James best

describes this document’s embodiment of the Enlightenment

ideals.

“The Constitution is

Toussaint L’Ouverture from the first line to the last, and in it

he enshrined his principles of government. Slavery was forever

abolished. Every man, whatever his color, was admissible to all

employments, and there was to exist no other distinction than

that of virtues and talents, and no other superiority than that

which the law gives in the exercise of a public function.”

Enter Napoleon

For a while it looked as though Haiti would

be allowed to continue as an independent state and a French

colony in name only, but soon the French executed Maximilian

Robespierre and returned to business as usual. Ultimately

Napoleon Bonaparte managed a coup d’état and proclaimed himself

emperor. He resolved to retake Saint Domingue for the French

plantation owners and quietly dispatched a huge force to crush

the slave revolt, reinstate slavery, and abolish the rights that

had been granted to the free blacks. The French force wound up

losing Napoleon’s brother-in-law (a reputed sadist) along with

24,000 soldiers and, due to the shame of being beaten by a bunch

of “barefoot slaves,” they formally attributed most their

deaths to yellow fever.

By 1803 Toussaint calculated

that the defeats of Napoleon’s emissaries should have reasonably

persuaded him to consider a peace accord. Toussaint’s offer was

that he would retire from public life if Napoleon would

recognize Haitian Independence. Within a few months, Toussaint

was drawn into a trap. He was invited to a negotiation meeting

and on Napoleon’s orders, put on a boat to France.

On realizing his betrayal,

Toussaint spoke these famous words to the ship captain: “En

me renversant, ils n’ont abattu à Saint Domingue que le tronc de

l’arbre de la liberté des noirs. Il repoussera par des racines

parce qu’elles sont profondes et nombreuses.” (In

overthrowing me, they have only felled the trunk of the tree of

black liberty in Saint Domingue. It will regrow from the roots

because they are deep and many.)

These words acquire greater

meaning with every decade that passes and never fail to make me

shiver. Now I can see Toussaint as a self-possessed man who

fully knows his worth. He is saying here that Napoleon is

deluding himself if he thinks he is decapitating the Haitian

Revolution. Toussaint appreciates that he is supported from the

grassroots: a concept that a top-down general like Napoleon

could never grasp. In addition, Napoleon could not have

understood that several other brilliant black commanders would

continue the fight. Toussaint’s fatal mistake was to

under-estimate Napoleon’s racism.

Thus on the orders of Napoleon,

Toussaint was thrown into a dungeon in the Jura mountains in the

French Alps. When the poet William Wordsworth learned about

Toussaint’s news, he wrote the following sonnet:

….Live, and take comfort. Thou hast left

behind

Powers that will work for thee; air,

earth, and skies;

There’s not a breathing of the common

wind

That will forget thee; thou hast great

allies;

Thy friends are exultations, agonies,

And love, and man’s unconquerable mind.

Toussaint died of cold and starvation in

Fort de Joux prison on April 7, 1803.

The Struggle Continues

As Toussaint predicted, other Haitian

revolutionaries continued the fight against slavery. At the

Battle of Vertières on November 18, 1803, the rebel army, now

led by General Jean-Jacques Dessalines, conclusively devastated

the French army led by Napoleon’s new emissary Rochambeau.

Consequently, within months of

killing Toussaint, Napoleon was forced to concede his loss of

Haiti by giving up his other New World possessions. This

included the sale of the French territory in North America to

the United States: Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana purchase.

Incidentally, Thomas Jefferson

agreed to allow slavery in the newly acquired territory when

U.S. Southerners pushed for it.

On January 1, 1804, with the

consummation of the first and only successful slave revolt in

history, Haiti’s self-emancipated slaves declared “The

Independent Republic of Hayti.”

Years later, during his exile

at Saint Helena, when Napoleon was asked why he had behaved so

dishonorably toward Toussaint. True to form, he replied: “What

could the death of one wretched Negro mean to me?”

The present has a way of

warping one’s perception of men, and it takes distance and

perspective to measure them. Three centuries later, the despotic

Napoleon is shrunk to size, and Toussaint continues to stand as

the giant he always was.

C. L. R. James said it best: “Toussaint

L’Ouverture was the finest product of that greatest period in

human history: The Age of Enlightenment.”

Sources: The Black

Jacobins, Toussaint and the San Domingo Revolution (1938), by

CLR James | An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti

(1805), by Marcus Rainsford | Wikipedia

Dady Chery is the editor of the website Haiti Chery,

where this text was first published. She is a journalist, playwright, essayist, and poet who writes

in English, French, and her native Créole. She hails from an

extended working-class family in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. She

holds a doctorate. |