|

Konplo Aristid la (The plot

against Aristide)

Li soti Washington (It came out of Washington)

Li pase

Vatikan (It passed through the Vatican)

Se

Bondye ki voye-l (It was sent by God)

Manno

Charlemagne

On Jul. 15,

2011, former Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide turned 58.

His birthday was marked in Haiti and its diaspora by scattered

celebrations of members and sympathizers of the Lavalas Family

(Fanmi Lavalas), the party he founded in 1996.

During the seven years he spent exiled in South Africa after the

2004 coup d’état against him, Aristide’s birthday was

commemorated by large demonstrations in the streets of

Port-au-Prince calling for his return. Over the past 25 years,

first as a liberation theology-inspired Salesian priest in the

1980s and then as Haiti’s twice elected (1990, 2000), twice

deposed (1991, 2004) President, Aristide had become a symbol of

the Haitian people’s demands for justice, democracy and

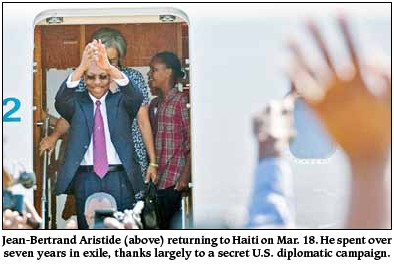

sovereignty. He received a spontaneous hero’s welcome from

thousands when he finally returned to Haiti on Mar. 18 aboard a

private South African jet. Much to the dismay of the Haitian

elite and foreign powers which overthrew him, he remained then,

and remains now, enduringly popular.

But

since returning to Haiti, Aristide has ventured out from his

home in Tabarre only once, due to concern over the threat of

attacks on him and his supporters. Newly installed right-wing

president Michel Martelly has, in the past, made no secret of

his antipathy for Aristide. He recently cut back Aristide’s

security detail and took back the government vehicle which

former President René Préval had provided Aristide on his

return. But

since returning to Haiti, Aristide has ventured out from his

home in Tabarre only once, due to concern over the threat of

attacks on him and his supporters. Newly installed right-wing

president Michel Martelly has, in the past, made no secret of

his antipathy for Aristide. He recently cut back Aristide’s

security detail and took back the government vehicle which

former President René Préval had provided Aristide on his

return.

In

a falsely magnanimous gesture, Martelly recently suggested he

would grant Aristide an “amnesty” (which he proposed also

for recently returned former dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier),

although Aristide has never been charged, much less convicted,

of any crimes whatsoever.

That may soon change. Right-wing mouthpieces like former

International Republican Institute (IRI) agent Stanley Lucas,

pro-coup historian Michel Soukar, and former anti-Aristide

opposition spokesman Sauveur Pierre Etienne have all recently

taken to the airwaves in Haiti and its diaspora to call for

Aristide’s prosecution with lurid and far-fetched charges of

corruption and political murder.

Haïti Liberté has

also learned from protected sources that a U.S. government team

is investigating Aristide (not for the first time) to see if it

can concoct a credible human-rights case against him.

This comes as no surprise. In reviewing some 1,918 secret

Embassy cables from April 2003 to February 2010 procured by the

media organization WikiLeaks, Haïti Liberté unearthed a

behind-the-scenes look at how the U.S. State Department was

pushing for Aristide’s removal from power in February 2004 and

strongly opposed his eventual return in March 2011.

But Washington feigns neutrality. A U.S. Embassy spokesman in

Haiti told Haïti Liberté after a press briefing last Nov.

23 that Washington had no position on Aristide’s return to his

country. “Aristide’s return? That’s a Haitian question,

that’s a Haitian decision,” said Jon Piechowski.

“So the U.S. would

have no say in that. . .”

“No,”

Piechowski responded, “I think whether Aristide stays

where he is or comes back to

Haiti, that's between him and

the people of Haiti.”

The secret U.S.

diplomatic cables show those statements are unequivocally false.

The cables not only bolster existing evidence of U.S.

involvement in the 2004 coup, but portray a sophisticated,

globe-spanning campaign afterwards to marginalize Aristide and

imprison him in exile.

When Aristide himself or officials from Caribbean nations like

the Bahamas talked of his rights, the United States flexed its

diplomatic muscles to oppose them. On one occasion, a U.S.

ambassador went so far as to angrily “pull aside” and

scold the Dominican Republic’s President.

The cables show how Washington actively colluded with the United

Nations leadership, France, and Canada to discourage or

physically prevent Aristide's return to Haiti. The Vatican was a

reliable partner, blessing the coup and assisting in prolonging

Aristide’s exile.

The cables also show continuity between the policies of the Bush

and Obama administrations toward Aristide. Under Bush in 2004, a

U.S. Navy SEAL team escorted Aristide on a jet into exile in

what Aristide called a “a modern-day kidnapping.” Six

years later, when Aristide announced his desire to return and

help after the devastating 2010 earthquake, Obama’s diplomatic

corps mobilized to block him. Obama himself called South

Africa’s President in a desperate failed attempt to keep

Aristide off the jet that finally flew him home.

More than two decades after Aristide first became

President, Washington’s campaign against him continues. Its last

big victory was the 2004 coup d’état, where we begin with the

intimately detailed information contained in the WikiLeaks

cables.

Bahamas shows “sympathy” and complains

U.S. is “hard-minded” Bahamas shows “sympathy” and complains

U.S. is “hard-minded”

The trove of Embassy communications

obtained by WikiLeaks unfortunately does not include many cables

from the Port-au-Prince embassy until March 2005. However,

secret cables from the neighboring archipelago nation of the

Bahamas during 2003 and 2004 clearly show Washington’s hostility

toward Aristide.

The very first cable of those

which WikiLeaks provided to Haïti Liberté is one from the

U.S. Embassy in Nassau on

Apr. 17, 2003. In it, U.S. Ambassador

J. Richard Blankenship reports about a meeting where Bahamian

Foreign Minister Fred Mitchell “described the U.S. position

on Haiti as ‘hard-minded’ , and called for continued dialogue.”

Washington, at the time, had

sought to invoke a clause of the Organization of American

States’ interventionist “Inter-American Democratic Charter”

in an attempt to find some pseudo-legal leverage to remove

Aristide. But “Mitchell was dismissive of the possibility of

invoking the democracy provisions of the OAS Charter, saying

that although ‘Some people argue that's the case in Haiti ... I

think that is taking it a little bit too far,’” the cable

said.

Washington was aware that the

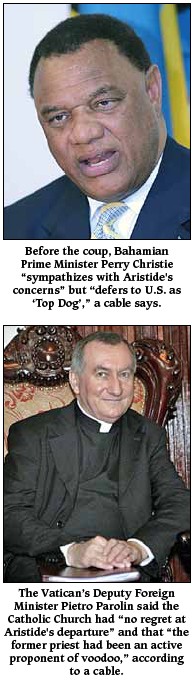

government of Bahamian Prime Minister Perry Christie was working

to shore up the besieged Aristide government, and Blankenship

sarcastically concluded his message: “While The Bahamas will

remain engaged on Haiti, the Christie government will resist any

effort to put real teeth into any diplomatic effort to pressure

President Aristide, preferring (endless) conversation and

dialogue to the alternative.”

There is another cable from the

Nassau Embassy’s Chargé d’Affaires Robert M. Witajewski dated

Feb. 23, 2004, about a year later and one week before the coup.

At a Feb. 19 event, “Prime Minister Christie twice came to

the Charge's table to request an ‘urgent’ meeting,”

Witajewski wrote. After the meeting which was held the next day,

Witajewski notes that the Bahamian Prime Minister “sympathizes

with Aristide's concerns.”

Christie reviewed with Witajewski

how at the United Nations days before Foreign Minister Mitchell

“called for the international community to ‘provide immediate

security assistance to bring stability to Haiti, including

helping the legitimate authority of Haiti to restore law and

order and disarm the elements that now seek to violently

overthrow the government, and who have interrupted humanitarian

assistance,” the Chargé wrote. “Mitchell continued using

-- for him -- unusually strong language: ‘Those armed gangs who

seek now to overthrow the constitutional order should be urged

to lay down their arms and if not they should be disarmed.’”

Christie pleaded that Washington “reconsider

its position against supplying the Haitian police with lethal

weapons, and at a minimum do more to support the Haitian police

with non-lethal support,” the cable notes. The Bahamian “indicated

some sympathy for Aristide's claimed plight, telling Charge that

‘there is simply no way that a demoralized police force of less

than 5,000 can maintain law in order in a country of more than 7

million.’”

Unfortunately, it seems that

Christie was also hopelessly clueless about the international

forces backing the soon-to-be accomplished coup, because in

daily phone calls with President Aristide, the cable says, “he

had stressed the importance of Aristide appealing directly to

the U.S., France, or Canada for assistance in re-equipping

Haitian police so that law and order could be restored,”

that is to the very countries which were backing the coup.

Christie was apparently so unaware

of the U.S. hand in the unfolding coup that “he had been in

contact with members of the U.S. Congressional Black Caucus to

allay their ‘deep concerns’ about the ‘good faith’ of the U.S.

and others in seeking a resolution to Haiti's crisis,”

concerns that proved to be completely justified.

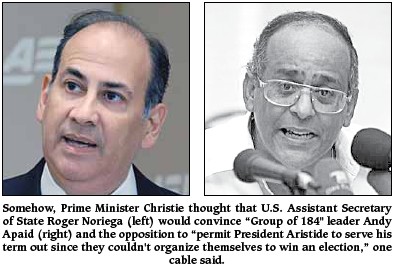

In perhaps his most naive

assessment, Christie urged that U.S. Assistant Secretary of

State Roger Noriega, one of Aristide’s most bitter critics in

the U.S. government, come to the embattled president’s rescue in

the face of calls for Aristide’s overthrow from the IRI-concocted “Group of 184" front, headed by sweatshop magnate

Andy Apaid. “Christie said that he was confident that A/S

Noriega ‘had the clout’ to bring Haitian Opposition leader Apaid

around, and that once Apaid signed on to an agreement, the rest

of the Opposition ‘would follow’ in permitting President

Aristide to serve his term out since they couldn't organize

themselves to win an election now,” Witajewski wrote.

Perhaps Christie was deluded into

thinking that the U.S. would recognize Aristide’s popularity.

Christie had witnessed it first hand as one of the few heads of

government to attend Haiti’s Jan. 1, 2004 bicentennial

celebrations, to which tens of thousands turned out despite an

opposition and international boycott. Christie “made clear

his position that President Aristide is Haiti's legitimately

elected constitutional leader,” Witajewski wrote, and also

provided “an evaluation of the state of the Haitian

opposition from his position as a practicing politician. ‘Even

with a year to organize,’ he said, ‘the opposition will not

match Aristide's level of support, and would lose if Aristide

decided to run again, which he will not.’”

In a cable the very next day,

Feb.

24, 2004, Witajewski reported that “The Bahamas seeks the

active support of the U.S. as the ‘most important’ member of the

Security Council as it engages on a full scale diplomatic press

to achieve peace in Haiti” and had “concluded that a

peaceful outcome without international intervention is

increasingly unlikely.”

In short, despite Christie’s

sympathy for Aristide’s situation, he “defers to [the] U.S.

as ‘Top Dog’,” the Feb. 23 cable concluded.

Encouraging “asylum” Encouraging “asylum”

The U.S. also asked the former Haitian

Ambassador to the Dominican Republic if he wanted political

asylum after he resigned his post on Dec. 18, 2003.

In a

Dec. 23, 2003 cable, U.S.

Ambassador Hans Hertell reported about his meeting with

Ambassador Guy Alexandre who resigned “due to what he

described as ‘incompatible principles’ with Aristide's

government” following the Dec. 5, 2003 confrontation at the

University of Haiti where “[a]ccording to Alexandre, police

officers broke both knees of one of his friends, a vice-rector

at a university.” (In fact, it was the university's rector,

Pierre Marie Paquiot, whose legs were injured – not broken –

under murky circumstances during a melee between anti-coup

popular organizations and pro-coup university students, while

the vice-rector, Wilson Laleau, suffered head injuries.)

Prompted by Hertell, Alexandre

said he would “not flee to the United States” and “has

no plans to seek asylum in the United States for now” but

rather “plans to reside in the Dominican Republic” and “get

involved in academia.”

“Requesting asylum, [Alexandre]

explained, would ‘further complicate Dominican-Haitian bilateral

relations’ and would not be in his nor Haiti's best interests,”

Hertell reported.

Had Alexandre requested U.S.

asylum, it would have helped Washington’s project of painting

Aristide as a political ogre. Instead, Alexandre “criticized

opposition groups' preoccupation with forcing Aristide's

departure without considering the consequences” and “emphasized

that Aristide's exit will not solve Haiti's socio-economic

problems,” Hertell wrote.

Alexandre also criticized the

anti-Aristide opposition “for their focus on grabbing power

rather than tackling the difficult problems of health, education

and infrastructure,” the cable said.

Vatican: “no regret” about coup

However, U.S. diplomats found much more

sympathetic ears at the Vatican.

In November 2003, a U.S. political

officer from the U.S. Embassy there met with the Vatican’s

Caribbean Affairs Office Director Giorgio Lingua, who said that

“the Vatican had noticed signs of increased discontent within

the Lavalas party” which he felt could best be fanned by “further

international pressure, especially from the United States, for

increased democratic expression within the country – without

directly challenging Aristide's legitimacy,” wrote U.S.

Chargé d'Affaires Brent Hardt in a Nov. 14, 2003 cable.

“Increased democratic

expression” was code for increased attacks on Aristide’s

constitutional government, which never once limited the “democratic

expression” of organizations or media openly calling for its

overthrow.

As this and later cables make

clear, “challenging Aristide’s legitimacy” and regime

change in Haiti were, in fact, the Vatican’s goals. Lingua told

the Embassy officer that “effecting change in Haiti should be

easier than in Cuba,” wrote Hardt. “Unlike Castro, Lingua

observed, Aristide is not ideologically motivated. ‘This is one

person – not a system,’ he added.”

But despite U.S. prodding, the

Vatican wanted to cloak its collusion. “When asked if the

October 16 incident [when anti-coup demonstrators protested at a

mass] might prompt the Holy See to raise its voice more

forcefully against Aristide's abuses, Lingua was noncommittal,”

Hardt wrote, “saying the Vatican needed to balance pressure

on Aristide against a delicate security situation on the ground.”

Lingua said “the Haitian bishops needed to tread lightly”

because of “Aristide's unpredictable nature,” according

to Hardt.

But the real reason the Church

hierarchy had to “balance’ and “tread lightly,”

the cable makes clear, is because Haiti’s Catholic Church was “divided”

between priests supporting Aristide and a hierarchy which did

not. (One exception was newly appointed Archbishop Serge Miot,

who Washington worried “was too close to the Aristide camp.”)

The result was “many people leaving the Church due to

disillusionment with its handling of the Aristide crisis,”

the cable says.

Progressive liberation

theologians, like Father Gérard Jean-Juste, were effectively

denouncing Washington’s growing destabilization campaign against

Aristide, and the Vatican’s supportive role, and “[a]ccording

to Lingua, Aristide’s exploitation of some clergy members for

propaganda purposes was taking its toll,” Hardt wrote. “Lingua

said Haitians see ‘a Church divided,’ with some clergy

supporting the Lavalas party and others against it. Lingua

claimed this lack of solidarity fostered disillusionment to the

point where people were leaving the Church in increasing

numbers.”

The problem was, in Lingua’s own

words, “the presence – in fact the omnipresence – of

Aristide,” the cable said.

The Vatican came out of the

shadows shortly after the coup was finally consummated on Feb.

29, 2004. On Mar. 5, 2004, U.S. Ambassador to the Vatican James

Nicholson wrote a cable reporting that the Holy See had “no

regret at Aristide's departure, noting that the former priest

had been an active proponent of voodoo.”

Nicholson learned this from

Embassy personnel who met with the Vatican’s Deputy Foreign

Minister Pietro Parolin, although “since February 29, the

Vatican has had no official public comment on Aristide's

resignation.”

Nonetheless, “even before

Aristide's departure, Pope John Paul II had appealed to Haitians

‘to make the courageous decisions their country required,’ and

had urged the international community and aid organizations to

do what they could to avert a greater crisis,” Nicholson

wrote. “This was seen as a veiled reference to Aristide's

leaving power.”

At that time, Lingua also told the

Embassy that the Vatican “saw no other way out of the crisis

and thought the former priest had to go.”

The Vatican understood it had an

important role to play in consolidating the coup, saying it was

“ready to work with a new transitional Haitian administration

to ensure a peaceful restoration of order,” Nicholson wrote.

Rome told its bishops “to exert a calming influence on the

populace,” which was outraged by the coup. But the Pope also

understood that his missionaries needed some steel behind their

gold crosses so called for “an international force [to]

quickly restore order in Haiti.”

Managing the backlash

In the days even before the coup was

consummated, the governments which backed it – the U.S., France

and Canada – began to insert “an international force” of

several thousand soldiers. They militarily occupied Haiti for

the three months from March 1 until May 31, 2004, and on June 1,

the 9,000-strong Brazilian-led United Nations Mission to

Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH) took over “restoration of order.”

But there was a backlash of

indignation against the coup and occupation from many Latin

American and Caribbean nations. CARICOM issued a Mar. 3

statement which expressed “dismay and alarm” about the

coup, noting the “public assertions made by President

Aristide that he had not demitted office voluntarily” and

demanding “an investigation under the auspices of the United

Nations to clarify the circumstances leading to his

relinquishing the Presidency.” CARICOM, which had proposed

an international force to protect Aristide’s government from “rebels”

and “restore order,” refused to take part in the

post-coup Multilateral Interim Force and called for Aristide’s “immediate

return.”

CARICOM also “questioned the

legality of the American-backed move to install Mr [Boniface]

Alexandre as president,” reported The Economist on

Mar. 4. CARICOM Chairman and Jamaican Prime Minister P.J.

Patterson said that the coup “sets a dangerous precedent for

democratically elected governments anywhere and everywhere, as

it promotes the removal of duly elected persons from office by

the power of rebel forces.”

A Mar. 9 cable by Nassau’s Chargé d’Affaires Witajewski provides a glimpse of the damage control

that Washington carried out in the face of such outrage.

Witajewski reports on a Mar. 8 meeting that he and his Political

Officer had with Dr. Eugene Newry, the Bahamian Ambassador to

Haiti.

Contrary to Prime Minister

Christie and Foreign Minister Mitchell, Ambassador Newry was

favorably disposed toward the coup. Perhaps due to his many “contacts

with the opposition,” Newry was “pleasantly surprised

with the transition now occurring” in Haiti and thought “it

was a good sign that the Haitian people overall had focused

their mistrust and dislike on the ex-President,” although he

did “fear [...] that Aristide's support network would

re-group in time for the next set of elections while the

Opposition coalition would fall apart fall once the ‘negative

force,’ i.e., Aristide, disappeared from the scene as an

effective player,” wrote Witajewski. (Newry also “did not

think that Aristide's attempts to regain support via press

encounters in the Central African Republic [where he was exiled

at the time] would impact on future Haiti developments.”)

Accordingly, Newry “downplayed

incendiary phrases in Caricom's statement on Haiti such as

expressing ‘alarm and dismay’ as matter-of-fact descriptions of

members' disappointment” and “claimed that Caricom is not

‘angry’ with the U.S. involvement in the departure of Aristide,

but rather was ‘surprised’ by the abrupt decision-making, and

Caricom's lack of involvement,” the cable said.

Newry also predicted “that

Caricom will be satisfied as long as their 10-point action plan

remains the basis for post-Aristide Haiti.” (Washington set

up a “Tripartite Commission” and a “Council of Wise Persons” as

earlier proposed by CARICOM.) Newry “concluded [that] Caricom

needs to get over its pique because ‘like a river, things must

move on’, and he understood that Haiti cannot advance without

the help that only the United States with the ancillary support

of other ‘major powers’ such as Canada and France could deliver,”

the cable said.

Newry told the Embassy what it

wanted to hear, but Witajewski, in his comments, also was aware

that the Bahamian “was perhaps overreaching in trying to put

a positive spin on Caricom's March 3 statement on Haiti and

reflecting more of the real politik position that The Bahamas

takes regarding Haitian migration than the more ideological

position of some of the other, less affected, Caricom members.”

CARICOM gets real

The Christie government’s “realism,”

as Witajewski called it in this cable, was apparent in another

from Apr. 6, 2004, when the Ambassador reported on Foreign

Minister Mitchell’s backpedaling during a Mar. 29 lunch meeting.

Mitchell “pursued his agenda of

downplaying the consequences of a division between Caricom and

the United States on Haiti,” Witajewski wrote. “Underlying

many of Mitchell's arguments was the premise that Caricom/The

Bahamas as small countries take (and are entitled to take)

principled stands while the United States necessarily engages in

real politik.”

Mitchell said that northern

Caribbean nations like the Bahamas are “cognizant of the

importance of their relations with the United States and thus

are more careful in balancing their interests with Caricom and

the U.S.” while southern Caribbean nations “are guided by

political agendas.”

Sensing he had his guest on the

defensive, Witajewski asked Mitchell “to clarify Caricom’s

call for an investigation into the circumstances of Aristide’s

resignation, [and] Mitchell sought to downplay its significance,”

the cable said. Mitchell “said that he personally envisioned

the ‘investigation’ as equivalent to resolution of a ‘routine

credentials challenge’ to a government such as occurs at the

UNGA [U.N. General Assembly] or another committee.”

However, Mitchell did have

the temerity to say “that the United States overreacted to

Jamaica’s offer to let ex-President Aristide reside in the

country and to Caricom’s declarations,” Witajewski wrote. “He

appeared to be arguing that Caricom was entitled to express its

views and not necessarily be held accountable for them. Mitchell

also claimed that despite Caricom’s verbal shots at the United

States over recent events in Haiti, there would be little net

impact on overall U.S.-Caricom relations... as long as the

United States didn't ‘overreact.’”

Mitchell upped the ante when he “insisted

that the United States should not be concerned with, or opposed

to, Aristide’s presence in the Caribbean,” a reference to

Bush administration officials’ remarks that Aristide should get

out of Jamaica and the hemisphere. Mitchell “argued that a

perceived ‘Banishing Policy’ has racial and historical overtones

in the Caribbean that reminds inhabitants of the region of

slavery and past abuse.”

Unfazed, Witajewski “inquired

on what would happen if Aristide were to meddle with Haitian

internal affairs and give his supporters the impression that he

is still a player in the future of Haiti,” which he had

every right to do. But Mitchell immediately became defensive and

“was emphatic that Jamaica will not allow Aristide to play

such an intrusive role and would ‘deal’ with Aristide if such a

situation were to arise,” the cable said.

Keeping the pressure on

Perhaps also afflicted with the “realism”

that governed Bahamian policy, other countries offered their

support to the U.S. campaign against Aristide. For example, in a

Nov. 22, 2004 cable, Guatemala’s acting Foreign Minister Marta

Altolaguirre told the Embassy there that she “agreed

wholeheartedly with [the] U.S. assessment” of Haiti and “volunteered

that her personal view was that Aristide had been a ‘disaster’

and could play no useful role in Haiti's future.”

Nigeria, after “consultations”

with Washington, also “offered Haitian ex-president Aristide

refuge in Nigeria for a few weeks before moving on to another

destination,” a Mar. 23, 2004 cable from the U.S. Embassy in

Abuja explains. The cable notes that Nigeria “has a history

of offering asylum to fleeing leaders” from collapsed

African dictatorships (like Liberia’s fallen strongman Charles

Taylor). This was a transparent attempt to associate Aristide

with such leaders.

After Aristide left Jamaica for

exile in South Africa on May 30, 2004, the US government worked

overtime to keep him out of Haiti and even the hemisphere,

rendering him a virtual prisoner-in-exile, even though the

Haitian Constitution and international law stipulate that every

Haitian citizen has the right to be in his homeland.

When Dominican President Lionel

Fernandez suggested in a statement at a hemispheric conference

nine months after the coup that Aristide should return and play

a role in Haiti’s democracy, the United States reacted angrily,

saying in a cable that Fernandez had “put a big front wrong

in advocating the inclusion in the process of former president

Jean Bertrand Aristide.”

The US Ambassador to the DR “admonished”

Fernandez “in a pull-aside at a social event.”

“Aristide had led a violent

gang involved in narcotics trafficking and had squandered any

credibility he formerly may have had,” US Ambassador Hertell

told him, according to a Nov. 16, 2004 cable.

“Nobody has given me any

information about that,” Fernandez replied.

No charges were ever filed against

Aristide for drug trafficking, although his lawyer Ira Kurzban

asserts Washington has tried. “The United States government

has spent, literally, tens of millions of taxpayer dollars

trying to pin something, anything on President Aristide,”

Kurzban told Pacifica’s Flashpoints Radio earlier this

month. “They’ve had an ATF investigation, a tax

investigation, a drug investigation, and now apparently some

kind of corruption investigation. The reality is they’ve come up

with nothing because there is nothing.”

Under the heading “Aristide

Movement Must Be Stopped” in an August 2006 cable, US

Ambassador to Haiti Janet Sanderson described how former

Guatemalan diplomat Edmond Mulet, MINUSTAH’s head, “urged

U.S. legal action against Aristide to prevent the former

president from gaining more traction with the Haitian population

and returning to Haiti.”

At Mulet’s request, UN Secretary

General Kofi Annan urged South Africa’s President “to ensure

that Aristide remained in South Africa,” where Aristide and

his family were living under an arrangement with the government

there.

In 2005, the Lavalas Family

planned large demonstrations to mark Aristide’s birthday. The US

Ambassador to France met with the French diplomatic official

Gilles Bienvenu in Paris to discuss the possibility of

Aristide’s return.

“Bienvenu stated that the GOF

[Government of France] shared our analysis of the implications

of an Aristide return to Haiti, terming the likely repercussions

‘catastrophic’,” wrote U.S. ambassador Craig Stapleton.

“Initially expressing caution when asked about France demarching

the SARG [conveying the message to the South African

government], Bienvenu noted that Aristide was not a prisoner in

South Africa and that such an action could ‘create

difficulties.’”

Stapleton swiftly overcame Bienvenu’s reluctance. Bienvenu agreed to relay U.S. and French

“shared concerns” to the South African government, under

the “pretext” (i.e. veiled threat) that “as a country

desiring to secure a seat on the UN Security Council, South

Africa could not afford to be involved in any way with the

destabilization of another country.”

The Frenchman went even further,

according to the Jul. 1, 2005 cable: “Bienvenu speculated on

exactly how Aristide might return, seeing a possible opportunity

to hinder him in the logistics of reaching Haiti,” Stapleton

wrote. “If Aristide traveled commercially, Bienvenu reasoned,

he would likely need to transit certain countries in order to

reach Haiti. Bienvenu suggested a demarche to CARICOM [Caribbean

Community] countries by the U.S. and EU to warn them against

facilitating any travel or other plans Aristide might have. He

specifically recommended speaking to the Dominican Republic,

which could be directly implicated in a return attempt.”

Five days later in Ottawa, two

Canadian diplomatic officials met with the U.S. Embassy

personnel. “‘We are on the same sheet’ with regards to

Aristide,” one Canadian affirmed, according to the Jul. 6,

cable. “Even before these recent rumors, she said, Canada had

a clear position in opposition to the return of Aristide.”

Canada shared the message with “all

parties... especially the CARICOM countries,” as well with

South Africa.

But “the South Africans

reportedly questioned whether it is fair to encourage Lavalas to

participate in the elections without their most important leader

being on the ground,” the cable said. “They are not

convinced of the good will of those who would exclude him being

there.”

Aristide’s exclusion from Haiti

during post-coup elections was essential, because Washington was

fully aware of his continuing popularity. U.S. Ambassador James

Foley admitted in a confidential Mar. 22, 2005 cable that an

August 2004 poll “showed that Aristide was still the only

figure in Haiti with a favorability rating above 50%” and

thus “Aristide's shadow continues to hang over the movement.”

So the Embassy’s dilemma was how

to keep Aristide in exile but still mobilize the Lavalas base

because, as Foley noted, the “degree to which the Lavalas

constituency participates in the election will be a large factor

in the legitimacy of the elections, and we are therefore

following developments inside the movement closely.” They

found an answer to their dilemma in the man once considered

Aristide’s “twin,” René Préval.

Préval remains bitter

The de facto post-coup Haitian

government that followed Aristide and persecuted his supporters

resolutely opposed his return. Then René Préval, formerly Prime

Minister in 1991 under Aristide, emerged as the frontrunner to

become president (for the second time) in Haiti’s 2006 election.

U.S. Chargé d’Affaires Timothy Carney reassured Washington that

"[i]n all his private dealings, Préval has consistently

rejected any further association with Aristide and Lavalas, and

bitterly denounced Aristide in conversations with the Charge and

other Embassy officers."

In his Dec. 14, 2005 profile of Préval, he

commented: "We see no credible evidence that Préval is

prepared to reconcile with Aristide or Lavalas leaders."

Publicly, Préval maintained that Aristide was

free to exercise his constitutional right to return to Haiti. Lavalas supporters voted for him in droves, expecting he would facilitate Aristide’s homecoming.

He did not.

The next year, Préval began to

worry that Lavalas would dominate the next legislative election,

take control of the government, and pave the way for Aristide’s

return. He met with Marc Bazin, a former World Bank economist,

presidential candidate, and long-time reliable partner of the

U.S. Embassy, who relayed the conversation to U.S. Chargé

d'Affaires Thomas Tighe.

"Préval seemed preoccupied with

Aristide, asking Bazin for his advice," Tighe wrote in a

Sep. 7, 2006 cable. "(Bazin suggested that Préval travel to

South Africa to tell Aristide personally that the political

situation was too delicate for his return. Préval responded that

‘the foreigners’ would never stand for his visiting Aristide.

This was, we trust, Préval's way of discounting a monumentally

bad piece of advice from Bazin.)"

When rumors swirled that Aristide would

relocate to Venezuela, Préval told U.S. Ambassador Sanderson "that

he did not want Aristide ‘anywhere in the hemisphere,’" she

noted in an October 2008 cable. The US was concerned but did not

believe the rumors to be credible.

There was no change in Washington’s policy

of blocking Aristide’s return with the Obama administration’s

arrival. Aristide himself held a press conference the day after

the Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake saying

he wanted to return to help with Haiti’s recovery.

“As far as we are concerned,

we are ready to leave today, tomorrow, at any time to join the

people of Haiti,

share in their suffering, help rebuild the country, moving from

misery to poverty with dignity,”

he said, close to tears.

Vatican

joins the fight

The U.S. Embassy’s Deputy Chief of Mission

(DCM) met with his counterpart at the Vatican to discuss the

earthquake and relief efforts days later. A Jan. 20, 2010 cable

reports, “In discussions with DCM over the past few days,

senior Vatican officials said they were dismayed about media

reports that deposed Haitian leader -- and former priest -- Jean

Bertrand Aristide wished to return to Haiti... The Vatican's

Assesor (deputy chief of staff equivalent), Msgr. Peter Wells,

said Aristide's presence would distract from the relief efforts

and could become destabilizing.”

Then the Vatican’s Undersecretary for

Relations with States, Msgr. Ettore Balestrero, called Archbishop Bernardito

Auza in Haiti, who “agreed emphatically that Aristide's

return would be a disaster.” The Vatican “then conveyed

Auza's views to Archbishop Greene in South Africa, and asked him

also to look for ways to get this message convincingly to

Aristide. DCM suggested that Greene also convey this message to

the SAG [South African government].”

U.S. efforts to block Aristide

from returning to Haiti continued up until the day he was

heading to the jet that would fly him back to Port-au-Prince.

UN Secretary Ban-Ki Moon and

President Obama both phoned South African President Jacob Zuma

asking that he stop Aristide from leaving South Africa before

the Mar. 20 run-off election, according to the Miami

Herald.

“Former

President Aristide has chosen to remain outside of Haiti for

seven years,” State Department spokesperson Mark Toner told

reporters days before Aristide boarded his plane, echoing the

Bush administration’s claim that Aristide had “chosen” to

leave Haiti in the first place.

“To

return this week could only be seen as a conscious choice to

impact Haiti’s

elections,” Toner

said, as if Aristide did not have the right to do so while the

U.S., which virtually dictated the results, did. “We would

urge former President Aristide to delay his return until after

the electoral process has concluded, to permit the Haitian

people to cast their ballots in a peaceful atmosphere. Return

prior to the election may potentially be destabilizing to the

political process.”

A

hero’s welcome

Aristide’s

return on Mar. 18 did nothing of the sort. “The problem is

exclusion, the solution is inclusion,” Aristide said during

a brief return speech at the airport after landing. And then he

made his only reference, however oblique, to the election from

which his party was barred: “The exclusion of Fanmi Lavalas

is the exclusion of the majority.”

Two days later the second round of Haiti’s election went off

without a hitch, but with record low participation by Haitians.

Some polling stations in Port-au-Prince were empty, with stacks

of ballot sheets sitting around, hours before they closed. Less

than 24% of registered voters went to their polls.

As the tropical sun came

out the morning of Aristide’s return in Port-au-Prince, nothing

seemed out of the ordinary. A 42-year-old mechanic, Toussaint

Jean, had come from the opposite end of the city with a few

friends to stand outside the airport’s chain-link fence.

“The masses of people haven’t really mobilized,”

he said, “because for three days they’ve been saying he’s

coming, but the Americans are putting pressure, and we think he

can’t return soon. Today you don’t see very many people. The

people are doubting – is he coming, is he not coming?”

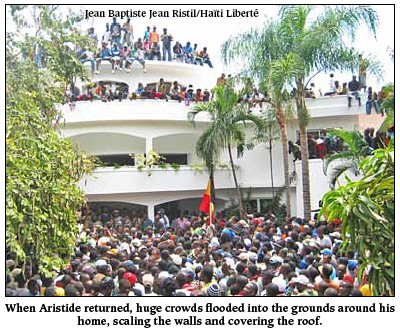

Nonetheless, by the time Aristide had touched down

and finished his speech, perhaps 10,000 people (estimates vary)

had gathered outside the airport in an exuberant demonstration.

They jogged alongside his motorcade waving Haitian flags and

placards bearing Aristide’s visage, then scaled the wall

surrounding Aristide’s home and poured into its grounds until

there was no room left to move. The crowd even climbed the

house’s walls and covered the roof.

Sitting in an SUV just 20 feet from the door to his

hastily repaired but mostly empty house (“rebels” had ransacked

it after the coup), Aristide and his family waited until a crew

of Haitian policeman managed to clear what resembled a pathway

through the crowd. First his wife and two daughters emerged from

the car and dashed inside the home.

Finally Aristide, diminutive in a sharp blue suit,

stood up in the car doorway and waved. The crowd roared in

excitement and surged around him. The path to the door vanished.

His security grabbed him and shouldered their way through the

sea of humanity until they got him to the house’s door, through

which he popped like a cork, clutching his glasses in his hands.

After a coup, kidnapping, exile, diplomatic

intrigue, and his rapturous welcome, Aristide was finally back

home. |