|

The first of three articles

“Haiti is open for business.”

That’s what President Michel “Sweet

Micky” Martelly said on Nov. 28 at a ceremony inaugurating a

giant industrial zone being built in Haiti’s north.

Across Haiti and abroad,

Martelly, his government, and “advisors” like former

President Bill Clinton have been pushing Haiti as a foreign

investor’s dream come true.

“We are ready for new ideas

and new businesses, and are creating the conditions necessary

for Haiti to become a natural and attractive destination for

foreign investment,” the new president said this fall in New

York City.

“The window of opportunity

is now,” an aide added. “Haiti has a new President and a

new way of thinking about foreign investments and job creation.”

The president might be new, and

there might be new actors on the scene, but there’s not much new

about the plans. Once again, Haiti’s government and her private

sector – and their international supervisors – are pitching

sweatshop level salaries as a key “comparative advantage.”

Assembly factories and free

trade zones have been part of Haiti’s “development”

planning for decades. Now, armed with billions of dollars in

grants, loans and private investment, Haitian and foreign

governments and business people are building a whole slew of new

factory zones as part of the country’s “reconstruction.”

Worse, they’ve chosen a piece

of fertile farmland for the showcase project: a giant industrial

park, heavily financed by US$124 million in US taxpayer dollars.

Six months from now, South Korean textile giant Sae-A Trading

will be opening its doors. Its plants will use as its waste

waterway a river that runs into the nearby fragile Caracol Bay.

In addition to running the risk of harming the country’s already

devastated environment, the new mega-factory will stitch

millions of garments for Wal-Mart, Target, GAP and other US

retailers, meaning that more U.S. workers will likely be knocked

out of their jobs.

Not one major media outlet – in

Haiti or abroad – has explored these and other factors of what

some have touted as a “win-win opportunity” for foreign

investors and the Haitian people. Indeed, many journalists have

been cheerleaders.

But the “new” Haiti has

definite winners and losers.

Haiti Grassroots Watch

spent months on an investigation, conducting over three dozen

interviews, visiting factory zones and workers in the north and

in the capital, and reviewing dozens of academic papers and

reports, including one leaked from Haiti’s Ministry of the

Environment. Among the findings:

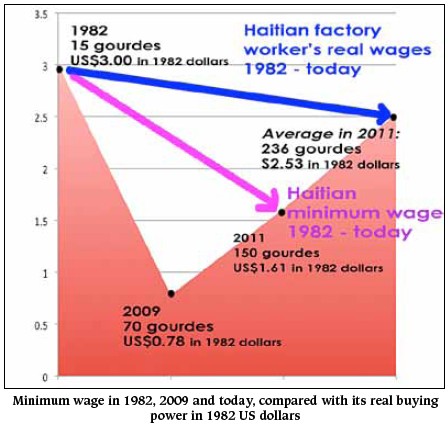

● Haitian workers earn less today than they

did under the Duvalier dictatorship.

● Over one-half the average daily wage is

used up lunch and by transportation to and from work.

● Haiti and its neighbors have all tried

the “sweatshop-led” development model – and it has mostly

not delivered on its promises.

● At least six Free Trade Zones or other

industrial parts are in the works for Haiti.

The new industrial park for the

north does not come without costs and risks: Massive population

influx, pressure on the water table, loss of agricultural land,

and it’s being built steps from an area formerly slated to

become a “marine protected area.”

In this series, the names of

workers have been changed to protect their identity because,

despite the fact that the Haitian Constitution recognizes the

right of free speech, and the right for workers to organize,

most workplaces are pervaded by fear due to the strong

anti-union sentiment. All interviews took place in the spring

and summer of 2011.

Salaries in the "new" Haiti

"I have a problem with my country,

Haiti,” said Evelyne Pierre-Paul. “I've been working in

factories here for 25 years, and I still don't have my own

house."

Pierre-Paul, 50, doesn't even

rent a house. Before the Jan. 12, 2010, earthquake, she and her

three children rented two rooms for 10,000 gourdes (about

US$250) a year. But the building was destroyed in the

earthquake. Twenty-two months later they are still living under

a tent, in one of the capital's hundreds of squalid refugee

camps.

Pierre-Paul's average daily

take-home wage is actually more than Haiti's rock-bottom

minimum. She earns about 225 gourdes or US$4.69 a day. But that

doesn't cover even half of what would be considered a family's

most basic expenses. Like all the other workers Haiti Grassroots

Watch (HGW) surveyed, only some of Pierre-Paul's children attend

school, and the family rarely eats meat. Pierre-Paul's average daily

take-home wage is actually more than Haiti's rock-bottom

minimum. She earns about 225 gourdes or US$4.69 a day. But that

doesn't cover even half of what would be considered a family's

most basic expenses. Like all the other workers Haiti Grassroots

Watch (HGW) surveyed, only some of Pierre-Paul's children attend

school, and the family rarely eats meat.

"When payday comes, you pay

all the little debts you accumulated, and you don't have

anything left," the worker told HGW.

Pierre-Paul sews clothes for

One World Apparel, a giant hanger-like factory owned by two-time

failed presidential candidate Charles H. Baker. The cloth comes

in duty-free, workers cut it up, stitch the pieces together, and

the clothing – for K-Mart, Wal-Mart and for uniform supply

companies – goes back out. Even though it’s not in a Free Trade

Zone (FTZ), The factory enjoys a number of tax benefits like a

15-year exemption on payroll taxes and no Value Added Tax,

thanks to the Investment Code enacted during the truncated

2001-2004 mandate of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. [Baker

helped lead the Feb. 29, 2004 coup d’état against Aristide -

HL.]

Currently, about 29,000

workers, about 65% of them women, cut and sew in Haitian textile

factories assembling clothes for Banana Republic, GAP, Hanes, Gildan, Levis, and dozens of other well-known labels. But if the

Martelly government, the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC),

the U.S. State Department, the World Bank, George Soros, and a

host of others involved in Haiti's "reconstruction" see

their visions realized, there will soon be 200,000 or even

500,000 assembly workers in FTZs and industrial parks all over

the country.

That prospect doesn't interest

Pierre-Paul too much.

One recent night, after a

ten-hour workday, the slightly hunched sewing machine operator

met with a journalist in one of her tent's "rooms." A

plastic table and a few chairs are jammed up against the canvas

walls. In the other "room," the worker has a bed where

she and all her children sleep. Clothes are neatly piled in the

corner. Pierre-Paul makes food – lots of spaghetti – on a

charcoal fire outside.

"I don't see any future in

this for my children," she commented.

That's not surprising.

Pierre-Paul's wages have one-third less buying power than they

did 25 years ago when she first began her factory career.

Minimum wage has gone from about US$3 a day in 1982 (in 1982

dollars) to 200 gourdes, which is about US$1.61 a day in 1982

dollars [about US$5 in 2011 dollars - HL] . Even taking into

account Pierre-Paul's slightly higher average wage, she still

makes only US$2.53 a day in 1982 dollars. [Haiti’s minimum wage

in 1982 was $2.64 a day - HL.]

Downwardly Mobile

During its investigation, HGW learned that

most workers today earn more than the minimum wage, but that the

salary remains less than it was in 1982.

An in-depth study conducted by HGW with eight workers in the capital and from the country's

biggest FTZ – the Dominican-owned CODEVI park on the

Haitian-Dominican Republican border – determined that the

average worker wage is about 236 gourdes a day – that's $2.53 in

1982 dollars. (Two factory owners, Baker and Clifford Apaid,

confirmed that average.) According to HGW's statistics, the

average worker's annual salary, including the traditional "thirteenth

month" bonus, would be about $153 a month or $1,989 per

year.

HGW's study also found that the

average worker spends more than half of his or her wage just

getting to work and back and eating lunch.

Averages of workers' typical commute and lunch expenses

|

Expense |

Gourdes |

US dollars |

Percentage of a day’s wage (236 g or $5.90) |

|

Transportation to and from work |

30.62 g |

$0.76 |

13% |

|

Main meal of the day (at work) |

90 g |

$2.25 |

38% |

|

|

120.62 g |

$3.01 |

51% |

Transportation and food represent only a

tiny percentage of a workers’ responsibilities. For example, the

average worker surveyed supports over four people, three of them

children. Average school fees carried for each worker, according

to HGW’s study, come close to US$690 annually.

While HGW could not verify all

of the figures, a recent study from the US- labor federation

came up with an even higher numbers for transportation, school

fees and other expenses. According to the AFL-CIO’s Solidarity

Center, a “living wage” for an average factory-worker

family with one wage-earner and two children should be about

$749 per month – almost five times the current average

assembly worker wage of $153 per month.

“This figure represents the

actual cost of living and serves as a baseline for an

appropriate minimum wage that will promote sustainable economic

development,” the Solidarity Center noted in its Mar. 3,

2011, report.

“The salary question is a

veritable scandal,” economist Camille Chalmers told HGW in

an interview. “The salary has gotten lower and lower, also.

[Workers] get paid in gourdes but in fact [because almost half

of food eaten in Haiti is imported], they consume in dollars.”

Pierre-Paul said she knows the

salary is not enough.

“I don’t have any choice,”

she explained. “My parents didn’t have me learn a skill, so

when I was 25, and I didn’t know what else to do, I resigned

myself to factory work.”

Pierre-Paul’s boss, factory

owner Charles H. Baker, admits the salary is not “livable.”

“If a person is honest, it’s

clear that it’s not enough,” Baker admitted. “If I could

give a worker 1,000 gourdes a day, I’d pay that. But the

conditions in Haiti don’t permit us to pay 1,000 gourdes.”

Baker and other factory owners

might claim they want to pay more than sweatshop wages but they

have fought salary hikes and unions ever since they got into the

game.

Under the Duvalier regime –

when wages were actually higher than today – only the

dictatorship-sanctioned “union” was allowed. Since then,

owners have (so far) nearly crushed any organizing efforts.

Thanks to the hard work of the

labor group Batay Ouvriye (Worker’s Struggle) and the courage of

workers there, who endured threats, job losses and even

beatings, over 3,000 laborers at the CODEVI park on the

Haitian-Dominican border belong to a union. The union negotiates

a collective contract for all the workers there.

This fall Batay Ouvriye and

textile workers got a union going in the capital. On Sep. 15,

organizers announced the new, legally registered Textile and

Clothing Workers Union (SOTA - Sendika Ouvriye Tekstil ak Abiman).

In less than two weeks, however, five SOTA executive committee

members had been fired, one of them from Baker’s One World

Apparel.

Batay Ouvriye’s spokeswoman

Yannick Etienne said the firings – which factory spokespeople

said were for “violations,” were totally predictable. “It’s

very coincidental that one week after the union is announced,

five committee members are fired,” she said. “They

decapitated the union.”

Asked about the incident, Baker

said his lawyer had advised him not to comment. But according to Batay Ouvriye, workers were fired after handing out leaflets in

the street, refusing to work overtime, and other actions which

are completely guaranteed by Haitian law.

After a long investigation, on

Nov. 24, 2011, a United Nations organization revealed that the

firings were not just. Better Work, an organization set up by

the UN’s International Labor Organization (ILO), noted that “there

is solid evidence showing that the representatives of SOTA were

fired because they belong to a union” and recommended “the

reintegration with back pay as a means of reparation” for

the union members.

The September firings are only

the latest in the three decades of repression and union-busting.

Anti-union, pro-"race to the bottom"

Evelyne Pierre-Paul has never been in a

union. As a sewing machine operator at Baker’s One World

Apparel, she's afraid to even talk about the subject.

"You have to create unions

in secret because if you utter the word, you can get fired,"

Pierre-Paul said. "The bosses say that if we form unions,

we'll destroy business."

National law and international

conventions guarantee Haitian workers the right to organize and

to collective bargaining. As recently as 2010, however, the

International Trade Union Confederation's (ITUC) Annual Survey

of Violations of Trade Union Rights noted that in Haiti "employers

have enjoyed absolute freedom" to repress organizers, due to

political turmoil and other factors.

"Those trying to organize

workers in a union are constantly harassed or dismissed,

generally in breach of the labor legislation,” the ITUC

survey reported. “To prevent workers from joining unions,

employers give bonuses to those who are not union members."

More recently, Better Work,

charged by the ILO with assuring all Haitian textile factories

taking advantage of the U.S. congressional HELP [Haiti Economic

Lift Program] act comply to international labor standards, said

much the same thing. In its April 2011 report, Better Work noted

numerous violations like the lack of written contracts, the lack

of proper record-keeping on hours worked, forced overtime and

too much overtime, failure to grant proper paid leave, and

failure to give proper lunch breaks. Better Work investigators

also noted that there were no unions in any of the

Port-au-Prince factories.

"Better Work Haiti notes

very significant challenges related to the rights of workers to

freely form, join, and participate in independent trade unions

in this industry in Haiti," the report said.

But while Better Work notes "significant

challenges" regarding the right to organize, director

Richard Lavallee admitted that his office can't do much to

assist that situation, aside from file reports and make

recommendations.

"Better Work has a

collaborative relationship" with the factories, he told HGW.

"Coercitive power doesn't come from Better Work."

Incredibly, Lavallee told HGW

that workers said they didn't understand the meaning of "union."

"When we interviewed workers

to ask if they had colleagues who were fired because of trying

to organize, we heard responses like, ‘What is a union?'" he

said.

Whether or not Lavallee really

believes that is possible, one thing is certain: factory owners

and supervisors know which workers speak with Better Work

investigators. Information in a report that criticizes a factory

or certain supervisor would be easy to source. It is highly

probable that workers exercise self-censorship.

That's certainly what workers

told HGW.

Ginette Jean-Baptiste operates

a sewing machine in Baker's One World Apparel. She was

interviewed by HGW away from the workplace. She echoed what

workers at Haiti's factories have said for decades: talking

about unions and organizing can lead to a pink slip.

"We can't make our demands

heard at all,” she told HGW. “You can't talk about that

even with each other because someone will tell on you and you'll

get fired."

Decades of Union-Crushing

In 2004, when Batay Ouvriye (BO) was

helping organize at the Dominican-owned maquila park CODEVI on

the Haitian-Dominican border, hundreds of workers were laid

off. BO and others claimed the lay-offs were a direct result of

the organizing. But at the time, Baker, then vice president of

the Association of Haitian Industries (ADIH), did not hesitate

to defend the Dominican employers.

"I'm very disturbed because

as a Haitian, I'm trying to create jobs," he told Inter

Press Service. "These people [BO and its international

supporters] are spreading lies on the Internet. This kind of

thing kills our business here."

But they were not lies. And

business was not "killed."

BO and the workers prevailed.

Today, over 3,000 workers at CODEVI are unionized and all

workers benefit from a collective bargaining agreement, although

salary remains rock-bottom. Minimum wage for the approximately

6,500 workers is 868 gourdes (US$21.70) a week.

In the face of local organizing

and international scrutiny and solidarity, Baker and other

industrialists fight tooth-and-nail against raises, saying they

pay as much as possible, and arguing that the foreign companies

who out-source stitching jobs to Haiti would pick up and leave

if workers were better paid.

Washington appears to agree. In

2009, with the backing of the US embassy, ADIH fought hard

against an attempt by parliamentarians to raise the minimum wage

to 200 gourdes (US$5) a day. As reported in Haiti Liberté

and The Nation, "contractors for Fruit of the Loom,

Hanes and Levi's worked in close concert with the US Embassy

when they aggressively moved to block a minimum wage increase"

voted by Parliament.

The U.S. State Department’s

Agency for International Development (USAID) helped pay for a

study that, not surprisingly, "found that an HTG 200 Haitian

gourde minimum wage would make the sector economically unviable

and consequently force factories to shut down," according to

what chargé d'affaires Thomas C. Tighe wrote in a confidential

cable to Washington. The US embassy urged "[a] more visible

and active engagement by [then-President René] Préval." Two

months later, the president apparently convinced the Parliament

to set a two-tiered minimum wage that allowed assembly

industries to pay less than 200 gourdes – 125 gourdes a day

until October 2011, and now 150 gourdes a day.

Justifying the "race to the bottom"

According to Baker, and to HGW research,

workers often earn more than 150 gourdes. But the wage remains

the lowest in the hemisphere – and lower than it was 30 years

ago – in a country where the state mostly does not provide nor

even subsidize basic needs like housing, electricity, water,

education and healthcare.

Industrialists justify the low

wages. "When you have a country where 80% of the people

don't, anything is good!" according to Baker.

The director of the Free Trade

Zone Office [Direction des Zones Franches], agreed. "A worker

can eat,” Jean-Alix Hecdivert told HGW. “Even if he can't

satisfy his hunger, he can eat."

At CODEVI, Director Miguel

Angel Torres echoed Baker. "I do think the salary is really

low, but Haiti has 70% unemployment!” he said. “If you

don't work, you don't have anything. If you get 868, at least

you can survive… It's better than nothing."

Haitian economist Camille

Chalmers has spent years thinking and writing about the

devastating effects of neoliberal economic policies on Haiti.

For Chalmers, sweatshop wages for exported textiles, produced by

local and foreign capitalists, are not "better than nothing."

"It's a big error to bet on

the slave-wage labor, on breaking the backs of workers who are

paid nothing while [foreign] companies get rich,” Chalmers

said. “It's not only an error, it's a crime."

The economist admitted that

assembly industries do create jobs but – referring to the

capital's main industrial park "boom" years in the 1980s – he

said that "while SONAPI [Société National des Parcs

Industriels] might have created 60,000 jobs, it also attracted

two million unemployed people."

Just like in Mexico, with the maquila boom, tens of thousands of landless peasants flowed into

Haiti's capital in search of jobs.

Assembly factories "don't

resolve the unemployment problem, they don't resolve the

production problem," Chalmers added. "They work with

imported materials, they're enclaves. They don't have much

effect on the economy."

Haiti's not the first place to

have "enclaves." International corporations based in

North America, Europe and parts of Asia have been off-shoring as

much labor as possible for decades in order to save on labor

costs. And as wages rise in one country, the companies pick up

and move on to someplace with lower wages. The concept of "race

to the bottom" is by now well understood.

CODEVI's Torres understands the

"race" well. Dominican factory owners started to move

across the border because "in the 2000s, we realized it was

too expensive in the Dominican Republic,” he said. “The

clients couldn't pay the labor costs."

In a report for Georgetown

University, Professor John M. Kline noted that rising labor

costs on the eastern half of Hispaniola, and the 2005 expiration

of "Multi-Fibre Agreement," led to the loss of over

82,000 jobs in the Dominican Republic between 2004 and 2008, "nearly

two-thirds of the sector's total employment," he wrote.

Ignorant or mendacious, the

cheerleaders for Haitian sweatshop labor fail to mention the

fate of those 82,000 Dominican workers. In fact, the Dominican

economy, supported by remittances, ranks in the top 25 countries

with the most skewed income distribution and has high structural

unemployment.

But that doesn't seem to matter

to former President Bill Clinton. Speaking to the September 20

session of the Clinton Global Initiative meeting in New York

City, he pushed Haiti to get to the front of the pack. "I

predict to you - if they [Haitians] do it right - they will move

to the top in the region and then they will spark this race all

over the Caribbean," he told investors.

Factory owner Baker admits he

is part of the race. "Yes, it's a race to the bottom… if you

count on it!" Baker said.

Baker claims that low-wage,

low-skilled assembly industries are temporary, a "stepping

stone," and that they will be a big part of the Haitian

economy for only about "ten or 15 years."

"I count on it only as a

stepping stone,” he said. “We're going up the stairs and

it's one of the steps."

Dozens of countries – and

indeed, Haiti, on and off for the past 30 years – have already

tread those same "race to the bottom" steps.

(Next week:

Why is Haiti “attractive” and what’s planned for Haiti?)

Haiti Grassroots Watch is a partnership of AlterPresse, the

Society of the Animation of Social Communication (SAKS), the

Network of Women Community Radio Broadcasters (REFRAKA) and

community radio stations from the Association of Haitian

Community Media.

To see images, video and to access links to primary sources -

http://www.haitigrassrootswatch.org

. |