|

The second of three articles

Why is

Haiti “attractive”

Last

September, President Michel “Sweet Micky” Martelly told

foreign investors that Haiti is ready for “new ideas and new

businesses.” The country, he said, is “creating the

conditions necessary for Haiti to become a natural and

attractive destination for foreign investment.”

But the ideas are not that new.

Over 30 years ago, the Haitian and U.S. advisors of dictator

Jean-Claude Duvalier had almost the same plan for Haiti’s

economy. The impoverished country would become the “Taiwan of

the Caribbean” – a vast factory complex offering low

sweatshop wages where U.S. industries could assemble textiles,

electronics and baseballs.

How has it worked out? Three

decades and billions of dollars in investments later, workers in

Haiti earn less than they did under “Baby Doc,” as

outlined in the first installment of this article. And studies

like Yasmine Shamsie’s Time for a “High-Road” Approach to EPZ

Development in Haiti note that “[w]hile the [Free Trade

Zone] model did create jobs, it also had important negative

effects on Haiti’s poor.”

Among the “negative effects”

the Canadian researcher noted:

● Increase in income concentration and

regional inequality

● A rise in food and housing prices

● Slums in marginal areas sprang up, in

part because of the rural exodus spurred by the factories, but

also because “wages were too low to provide workers with

decent or safe accommodations.”

Those results haven’t stopped

Haitian politicians and “development experts” from doing

“déjà vu all over again” planning. This time, however,

plans call for “decentralizing” the factories.

In 2002, President

Jean-Bertrand Aristide kicked off the new round when he and

Parliament passed sweeping “Investment Code” and “Free

Trade Zone” legislation. The new laws offer 15-year tax

holidays, duty-free import and export, and tax-free repatriation

of profits. Only one Free Trade Zone (FTZ) opened last decade –

CODEVI on the Haitian-Dominican border – but others were in the

works prior to the Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake, thanks to the

incentives offered by duty-free textile trade agreements with

the U.S..

In fact, the changes in the

international garment industry during the last decade – due to

the 2005 expiration of the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) and the

Agreement on Textiles and Clothing which gave developing

countries low-duty or duty-free export quotas for the U.S.,

Europe and other “developed” countries – have created havoc.

When those agreements ended,

thousands of factories in low-wage countries around the world

shut their doors or laid off workers as international

contractors sought out more advantageous locations to have their

clothes stitched. Perhaps not coincidentally, the very next

year, in 2006, the U.S. Congress passed the Haitian Hemispheric

Opportunity through Partnership Encouragement (HOPE) Act that

gave preferential access to Haitian-sewn clothing. Two years

later, HOPE II expanded the preferences and locked them in place

for ten years.

Then, in the wake of the

earthquake, Congress approved the Haiti Economic Lift Program

(HELP) Act, which nearly triples duty-free quotas for clothing

exports from Haiti to the U.S. and stretches the access up

through 2020.

But the names “HOPE” and

“HELP” shouldn’t mislead readers into thinking the

legislation is meant to be “hopeful” or “helpful”

to Haitian factory owners or workers only.

Writing for the United Nations

in 2009, economist Paul Collier noted that “[u]niquely in the

world, Haiti has duty-free, quota-free access to the American

market guaranteed.”

“Haiti has a massive

economic opportunity in the form of HOPE II,” Collier wrote

in his Haiti: From Natural Catastrophe to Economic Security

report for UN General Secretary Ban Ki-moon. “The global

recession and the failure of the [World Trade Organization] Doha

Round accentuate this remarkable advantage because manufacturers

based in other locations will undoubtedly be fearful that rising

protectionist pressures may threaten whatever market access they

enjoy currently. From the important perspective of market

access, Haiti is now the world’s safest production location for

garments.” [author’s emphasis]

Collier and the other

cheerleaders say Haiti won’t be able to sell its “unique”

advantage unless it carefully assures a few sine qua nons.

Low wages

Wages must be kept low. A World

Bank/Inter-American Development Bank report prepared for the

2011 Davos World Economic Forum noted that, at the moment,

Haiti’s labor costs were “fully competitive with China’s,”

while wages in the Dominican Republic are “high,” which

has led to a “decline” in the assembly industry there.

What are the wages across the

border in the DR? In 2009, the minimum wage for Free Trade Zone

workers was US$35 a week, which, according to the US State

Department – cited in a study by Georgetown Professor John M.

Kline – “did not provide a decent standard of living in any

industry for a worker and family.”

The implication? Haitian

sweatshop wages won’t be going up any time soon. They currently

stand at about $35 a week.

24/7 production

The clothing industry “operates

multi-shift production,” Collier noted in his report, where

he called for Haitian factories to include night shifts. The

Haitian private sector agrees. In its post-earthquake Vision

and Roadmap for Haiti report, Haiti’s industrialists and

business owners called for “flexible labor laws, including

immediately legalizing the 3x8 work shift to allow increased

competitiveness in the garment industry.”

Public investment

Not surprisingly, Haiti’s would-be

sweatshop investors are also looking for subsidies and handouts.

“Given the risk and timing associated with garment tenants,

public funding is necessary to catalyze investment in the new

economic development zones,” the Vision and Roadmap

noted.

The factory owners got their

wish – the U.S. and other donors are donating almost $200

million to the new Regional Industrial Park of the North (Parc

Industriel du Region Nord - PIRN) project in Caracol (see

below).

Land for

FTZs

“Ensure that

land is rapidly available for acquisition in Export Zones,”

Collier recommended.

All of these

elements will make sure that Haiti is, as Martelly called it, “a

natural and attractive destination.”

What’s planned

for Haiti?

“Free Trade

Zones should be one of the spearhead’s to launch reconstruction,”

recently said Jean-Alix Hecdivert, director of the Haitian

government’s Free Trade Zone Office (FTZO).

Beginning 40 years ago, Haitian authorities and their backers

pinned their hopes – in part – on Free Trade Zones (FTZs) and

assembly jobs.

More

recently, the Haitian government and its backers have nuanced

their approach. The 2010 Presidential Commission on

Competitiveness: Shared Vision for an Inclusive and Prosperous

Haiti report named textiles as one of five “priority”

sectors. (The other four are: animal husbandry, tourism, fruits

and tubers, and construction.)

But

in the wake of the earthquake, and with the advent of the HELP

law which extends the HOPE II benefits, the main focus appears

to be on FTZs and the assembly industry sector. The FTZO has

received many requests for new authorizations, Hecdivert told

Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW).

“We

are working on all of these projects because the focus is:

create the most jobs possible in the shortest amount of time,”

he added.

Echoing Hecdiovert, a key figure in the Martelly administration

said the government is basically banking on “a massive influx

of foreign capital.” In a Sep. 12 article in Le

Nouvelliste, Laurent Lamothe, head of Martelly’s new Council

on Economic Development and Investments, said “the biggest

need for the Haitian population is job creation.”

According to HGW’s interviews with the FTZO, and the evidence

culled from dozens of documents and reports, there are over a

half-dozen new FTZs and other assembly industry-related projects

in the works. These include FTZs, Free Trade Industries

(essentially an FTZ that the size of the building) and “Special

Economic Zones” which are like expanded FTZs but with some

non-FTZ businesses allowed in the region. One of the biggest

projects is the PIRN. Another large project – although not much

is known about it – is a giant combination of FTZs and other

initiatives some journalists are calling the “North Pole

Initiative.”

Despite numerous requests to FTZO officials, HGW was not able to

obtain definitive paperwork on all of the projects, nor a map of

approved FTZs. Below is an incomplete list of existing or

potential FTZs and related projects.

|

Name |

Where |

Who |

Who is

investing & what kind of investment |

Number of new

jobs project aims to create |

|

SONAPI

industrial park (expansion) |

Port-au-Prince |

(government

industrial park) |

Government -

$3.5M loan

Government -

$400K grant |

1,200 - 2,000 |

|

CODEVI

(expansion) |

Ouanaminthe |

Grupo M |

World Bank &

Soros Economic Development Fund (SEDF) - $6M loan

Citi - $250K

grant |

1,400 |

|

West Indies

Free Trade Zone |

north of

Port-au-Prince (part of “North Pole”) |

WIN Group (Mevs

family) |

Soros

Economic Development Fund (SEDF) - $45M loan |

25,000 |

|

Industrial

Revolution II |

Croix des

Bouquets |

Richard Coles

of Multiwear S.A. |

$7.5M total,

with a $3M loan possibly coming from IDB |

? |

|

RHEA |

Croix des

Bouquets |

Signa S.A. |

? |

? |

|

? |

Corail-Cesselesse

(part of

“North Pole”) |

NABATEC -

Gérald-Emile Brun, director |

Unnamed

Korean firm? |

? |

|

HINSA |

Drouillard

(Port-au-Prince) |

Hispaniola

Investment S.A. (D’Adesky) |

|

? |

|

PIRN |

Caracol |

US

government, Haitian government, Sae-A |

US - $120M

grant

Inter-american

Development Bank (IDB) - $55M grant

Sae-A - $78M |

20,000 (more

promised) |

|

Quisqueya |

Sartre |

? |

? |

|

|

? |

Les Cayes |

? |

? |

|

|

Nouveau

Quisqueya |

Port à l'Ecu |

Société Générale de Développement S.A.

(SOGEDEV) |

(tourism

installation as well as FTZ planned, according to FZO) |

|

|

? |

Fort Liberté |

? |

? |

|

|

? |

Ganthier

(part of “North Pole”?) |

? |

? |

|

Charity or

profit?

The language in

the press releases and on the websites announcing the millions

in loans and grants for the expansion of the textile assembly

industry constantly reinforces the idea that relocation of

factories to Haiti is practically a charitable enterprise.

The

Interim Haiti Recovery Commission says the project is in the “job

creation” sector, making it sound almost like a social

service. Billionaire George Soros’ investment group hyped that

their participating in the West Indies Free Trade Zone would “improve

the standard of living for 300,000 residents.” A Citi news

release on its $250,000 grant to CODEVI congratulated itself for

helping “create 1,400 new full time jobs for Haitians over

the next 12 months.”

But a

look at what the buying power of a Haitian textile worker’s

salary dispels the myth that assembly jobs contribute to a

significantly improved “standard of living.” And in any

case, an investment is an investment – the objective is to make

a profit. That is why financiers like Soros and Korean textile

giants like Sae-A Trading are in Haiti, not in Alabama or

France.

The

jobs “created” in Haiti most likely already existed as

jobs in another country before moving to the home of the

hemisphere’s lowest wage. Haitian laborers are likely replacing

more expensive laborers, and are basically making it possible

for clothing labels like GAP, Banana Republic, Gildan, Levis and

others to make even more profits by shutting down factories

based in countries with better salaries and better worker

protections.

A

look across the border is instructive. Between 2004 and 2008, as

wages rose a tiny bit, and a preferential trade agreement came

to an end, the Dominican Republic lost 82,000 assembly jobs.

In

the US, during about the same period (between 2004 and 2009),

over 260,000 textile workers lost their jobs, according to the

US Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. sewing machine operators –

the least trained textile workers – earned about $9.50 an

hour in 2008 (the most recent figures available). In Haiti

they earn about $5.90 a day.

Manufacturers do not take their jobs offshore in order to “jumpstart”

industry or “improve the standard of living.” They do it

to make a profit. As Canadian company Gildan Activewear said in

a recent newspaper article, the savings offered are “too good

to pass up.”

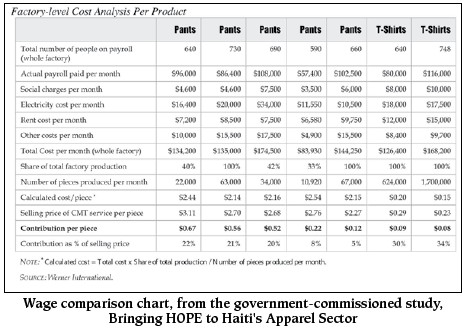

According to a 2009 study commissioned by the Haitian government

and paid for by the World Bank, Haitian assembly plants seem to

be making a good profit, also. At that time were netting between

8 and 67 cents profit per piece, with factories stitching

up to 1.7 million items per month.

Not all bad

Industrialization

brings some benefits. Haitian workers get training, industrial

parks are built, and there is likely some transfer of

technology. Electricity, water and other infrastructure is

usually improved in the FTZ areas. But the industry is volatile,

and at any moment a textile company can pick up and leave.

For these and other reasons, Haitian

economist Camille Charmers thinks the current approach –

marketing Haiti’s sweatshop-wage salaries – is “a big error.”

“Basing

the country’s development on assembly industries is a big error,

it will lead us into a hole, into dependency,” he told HGW.

“We’ve already experienced it, we know what it does.”

While

Chalmers admitted that the areas with FTZs have slightly better

infrastructure than the rest of the country, and that workers

use their meager wages to buy food, the overall effects are

minimal and do not help the economy’s productive forces grow.

“The

sector is practically cut off from the rest of the country,”

he said. “You get some factories and some salaries, and

everything else is imported.”

“It’s

completely wrong-headed and it won’t help the country get out

from under its economic crisis,” the economist concluded. “People

need to know what FTZs are, what has happened in Mexico, or

Honduras, so they don’t think these things will ‘save’ us.”

So

how have other countries fared?

Stepping Stone

or Dead End?

Haitian factory

owner Charles H. Baker admits that by trying to attract

manufacturers to Haiti with the lowest salary in the Americas,

the country is engaged in a “race to the bottom,” but he

insists that low-wage, low-skilled assembly industries are a “stepping

stone” to more complex industrial development.

“It

will last ten to 15 years,” Baker told HGW. “I count on

it only as a stepping stone... It’s a step. We’re going up the

stairs, and it’s one of the steps.”

Dozens of countries – and indeed, Haiti, on and off for the past

30 years – have already walked the walk, climbing onto the

bottom of the “race to the bottom” steps.

HGW

reviewed reports on the Dominican Republic, Mexico and Central

America to see how those countries, economies and workers have

done.

Resoundingly, the evidence on Free Trade Zone (FTZ) and low-wage

assembly industries shows: Economy - Little evidence of “linkages”

with the rest of the economy; Environment and Health -

Assembly industry-led industrialization can have direct and

indirect negative effects on the environment, and lax

regulations or lax enforcement can mean that workers are exposed

to hazardous materials; Society - While the employment of

women does yield some positive effects (economic autonomy,

etc.), assembly industries can also have negative effects on

families and society.

“The

literature on [Export Processing Zones] is voluminous but there

are a few findings that stand out when considering Haiti,”

notes Canadian researcher Yasmine Shamsie. “First, countries

that applied the EPZ model relatively successfully (such as

Mauritius and Costa Rica for instance) employed it as one pillar

of a broader plan to diversify their economies. This means that

the model on its own will yield hardly any beneficial results.”

What does the

data say?

HGW cannot claim

to have perused all of the literature, but a glance at some

studies of countries similar to Haiti might shed some light…

Economy

In 2003, José G.

Vargas Hernández of the University of Guadelajara looked at

literature related to Central America where, during the 1990s at

least, “most of the maquiladoras are owned by Asian capital,

mainly Korean capital investors.”

The

researcher concluded that “[t]here is no evidence that

maquiladora industry’s technological complexity has a direct

impact both in economic development and generation of well

remunerated employment.”

Vargas Hernández went on to discuss universal “non-observances

of labor rights,” the fact that foreign investors can leave

a host country on a moment’s notice, and the frequent failure of

the sector to develop beyond simple low-skilled, and low-wage

jobs.

“There

is not a clear understanding about the role that this type of

industry is playing in economic growth and national development,”

the researcher wrote.

In an

exhaustive 2008 literature review, two US-based professors

concluded that even Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and the

creation of high-tech assembly industry don’t necessarily

produce “spillover” into the local economy. In

Comparative Studies in Comparative International Development,

Eva A. Paus and Kevin P. Gallagher looked FDI in Mexico and

Costa Rica. For the latter, they found “some positive

spillovers from FDI through the training, education… [but]

spillovers via backward linkages [to the rest of the economy]

have been small.”

Hopes

were very high for Mexico, which had an indigenous electronics

and computer industries prior to the FDI boom. Rather than

source parts in Mexico, however, the foreign companies got

inputs wherever they were cheaper – usually from Asia.

“Under

the Washington Consensus, governments in both countries had

great faith in the power of liberalized markets to render

economic stability and growth, and for FDI to generate

technological and managerial spillovers,” the authors wrote.

“Our article contributes to the growing body of evidence that

the Washington Consensus does not constitute a viable

development strategy.”

Along

the Mexican-U.S. border, home to the maquiladora boom,

especially following the implementation of the North American

Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), income disparity is higher than at

any other commercial border in the world, a 2007 article in the

Golden Gate University Environmental Law Journal reports.

Minimum wage in Tijuana buys one-fifth what it did in the early

1980s, and “67% of homes have dirt floors, and 52% of streets

are unpaved,” researcher Amelia Simpson wrote.

Environment

and Health

There are

generally two types of environmental concerns associated with

assembly industry plants – direct environmental damage due to

waste, and indirect damage or effects, due to increased pressure

on the water supply from both the industry and the typical

population influx inspired by the hope of jobs.

Damage or benefits to the environment appear to be highly

dependent on the ability of the host country to enforce laws and

standards. Some studies claim that assembly industry factories

are more careful about the environment because they know foreign

consumers might boycott a polluting industry.

A

2002 UN report on Mexico found that “the maquiladora industry

performs better than the non- maquiladora industry with respect

to direct environmental externalities.”

The

case of the blue jeans water run-off in the Mexican state of

Puebla is by now well-known. In order to “fade” jeans,

they are usually beaten or chemically treated. Tehuacán means “Valley

of the Gods,” but reporters call it “Valley of the Jeans.”

A 2008 study from Ciencia y el Hombre journal in Veracruz

reported blue dye run-off polluting rivers and irrigation

ditches. Of equal or greater concern is the increased demand on

water supply, Blanca Estela García y Julio A. Solís Fuentes

wrote.

“Due

to the intensive use of water, the water table is diminishing

between 1 and 1.5 meters every year, at the same time the

population is growing between 10,000 and 13,000 people per year,”

they noted.

In

some parts of Mexico, factories now buy “water rights”

from local farmers in order to cover their needs, harming

agriculture and driving up the cost of water. The 2002 study

noted that: “The shortage of water, both in quantitative and

qualitative terms, has already forced the industry to start to

purchase water rights, temporarily or permanently, from

surrounding agricultural water shareholders. These water rights

are traded with high market prices. One example is Nissan’s

automotive plant in Aguascalientes that purchased water rights

required for its painting processes.”

The

NAFTA has an environmental “side agreement” that calls

for companies to clean up after themselves, but the 2007 Golden

Gate article noted that the agreement is neither “enforceable”

nor has it “brought adequate protections for workers or the

environment.”

Surveys of Haitian factories attest to the lack of protections

for workers from environmental hazards. Better Work Haiti found

that almost all factories violated national and international

laws and standards. “Average non-compliance rates are high

also for Worker Protection (93%), Chemicals and Hazardous

Substances (89%) and Emergency Preparedness (82%).”

According to the April, 2011, report, “factories initiated

remediation efforts to improve the situation,” but as noted

earlier, Better Work does not have enforcement powers.

Society

As the record in

Haiti shows, the installation of assembly industries and FTZs

can have dramatic effects on population movement. According to

Simpson, in Mexico, the maquiladora industry “triggered the

largest migration since the 1960s.”

“Tijuana’s

population increased more than sevenfold from 1960 to 2000,”

she wrote.

Society is also

impacted in another way. More than any other industry in poor

countries, assembly plants employ women. In some countries, the

workforce is up to 80% female, often young. Women are preferred

because, according to Canadian researcher Yasmine Shamsie,

quoting another researcher, “they are cheaper to employ, less

likely to unionize and have greater patience for the tedious,

monotonous work employed in assembly operations.” (In Haiti,

the balance between women and men is more even. Women make up

about 65% of the workforce.)

The

impact on women can be both negative and positive. On the

negative side, women are exposed to the toxic chemicals, develop

injuries due to movement repetition, and can contract

respiratory illnesses. On the other hand, having an independent

income – albeit insufficient – can be empowering.

Still, women are usually the primary care givers for children. “Family

life, the foundation of every community, has deteriorated under

the influence of the maquiladoras,” wrote Richard Vogel

about Mexico’s Ciudad Juarez in 2004 for the Houston Institute

of Culture. “About half of the families that reside in the

two and three room adobe houses in the working-class

neighborhoods of Juárez are headed by single mothers, many of

whom toil long hours in the maquiladoras for subsistence wages.

The resulting stress on families has lead to chronic problems of

poor health, family violence, and child labor exploitation.

Children suffer the most. Because of the lack of child-care

programs, kids are often left home alone all day and fall prey

to the worst aspects of street culture, such as substance abuse

and gang violence. Ciudad Juárez, by any measure of social

progress, is moving backward rather than forward under the

influence of the maquiladora industry.”

(Next week:

Industrial Park in Caracol: A “win-win” situation?)

Haiti

Grassroots Watch is a partnership of AlterPresse, the Society of

the Animation of Social Communication (SAKS), the Network of

Women Community Radio Broadcasters (REFRAKA) and community radio

stations from the Association of Haitian Community Media. To see

images, video and to access links to primary sources -

http://www.haitigrassrootswatch.org

. |