|

The

third of three articles

The

case of Caracol

Robert Etienne looks out with dismay at the fence

cutting through his field in Fleury, near Caracol, in Haiti’s

Northeast department. Earlier this year, he had a healthy crop

of beans coming up through the rich, black soil.

“The first week of January,

tractors moved across all this area and broke down everyone’s

fences,” the septuagenarian told Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW)

during a June, 2011 visit. “Thieves and animals followed, and

our crops were gone.”

Etienne brought up his four children right here, by

raising animals and farming a small family-owned plot and a

larger plot he leased from the state. Along with hundreds of

other farmers in this community , he woke up one day last

January to discover his fields had been destroyed.

Unbeknownst to Etienne and other farmers, that same

week the Haitian government (GOH) signed an agreement with U.S.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, representatives of the

Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and the Korean textile

giant Sae-A Trading. With those signatures, Etienne’s land and

about 300 other plots were converted into an industrial zone.

“This will be the match that strikes a fire, and

gets things going,” Hillary’s husband, former U.S. President

Bill Clinton, told the Wall Street Journal. Clinton, who

at the time headed the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC),

has long-championed plans to bring more industry to Haiti.

But farmers like Etienne, along with labor leaders,

environmentalists and economists, are all wondering – just what

“fire” has been lit and when “things get going,” what “things,”

and where will they “go?”

Also, why was Caracol chosen?

All parties agree that the site – which is part of

the Trou du Nord River watershed – is one of the most fertile

spots in the Northeast Department. The new industrial park will

also be located only about five kilometers from a large bay

which is home to one of the country’s last mangrove forests and

extensive coral reefs.

In order to find out why Caracol was chosen, and to

get a better picture of the potential “winners” and “losers” in

the project, HGW visited the Northeast, reviewed a half-dozen

studies, and interviewed numerous experts and potential

beneficiaries.

PIRN - A

public-private partnership

The Industrial Park of the North Region (Parc Industriel de la

Région Nord - PIRN) is the showcase reconstruction project for

the new government, the CIRH and the “international community”

in Haiti – U.S., France, Canada, the European Union and the IDB.

The 243-hectare industrial park is slated to open in March 2012.

Planners say some 20,000 people will be hired for “Phase 1,” and

that up to 100,000 new direct or indirect jobs, the overwhelming

majority of them sweatshop wage-level assembly jobs, will be

created over the next few years.

In the planning stages before the earthquake, and

with an initial price ticket of over US$200 million, the PIRN is

the result of a “public-private partnership.” But the

Government of Haiti (GOH) is not the only “public”

partner.

The “public” to the north – U.S. citizens –

is the project’s biggest investor, providing some US$124 million

in U.S. tax dollars. That financing that will be used (according

to project documents) to improve nearby port infrastructure,

build a electricity plant to supply power to the PIRN, and build

at least 5,000 units of housing.

As Bill Clinton implied, foreign investment is a key

part of the economic plan he and the Haitian government are

pushing. Washington is doing everything it can to help assure

Haiti is “open for business.” Thus, at a briefing on Jan.

7, 2011, U.S. AID Director Cheryl Mills was proud to report that

her team had “been working through

with foreign investors on how we could go about attracting them

to an industrial park.”

In addition to U.S. tax dollars, the PIRN is also

being funded by the IDB to the tune of US$50 million. The IDB

money will be used to build “factory shells and

inside-the-fence infrastructure,” according to U.S. State

Department documents.

The use of taxpayer dollars to subsidize private

business is nothing new. “Public Private Partnerships”

(PPP) are common the world over. The taxpayers take risks to

make a location or a sector attractive for private capital. And

while the overall logic and justice of PPPs in general could

certainly be debated, the specifics of this PPP really stand

out. It goes further than most. It uses tax dollars – mostly

from the U.S. – to benefit textile and clothing companies that

are not necessarily American, and every job created there will

likely result in lay-offs of workers in U.S..

Ultimately, in the case of the PIRN at least, U.S.

taxpayers are making it easier and cheaper for foreign and local

clothing and textile companies to set up (sweat-)shops in Haiti,

lay off better paid workers in the U.S. and other countries, and

increase their profits. If Levis and the GAP can get their

clothes stitched in a place that pays $5 a day rather than $9 an

hour (approximately the lowest wage paid in US-based clothing

factories), with new infrastructure, electricity, UN

“peacekeepers” to provide security, and tax-free revenues and

other benefits, why not?

Ironically, the main private partner in the

PIRN is not Haitian or American. The partner is South Korean

textile giant Sae-A Trading, which promises to spend $78 million

to build a 50,000 hectare factory complex that eventually

employs 20,000 workers (in the first phase) and which will

eventually include a textile mill that will do knitting and

dyeing.

Sae-A Trading is one of the worlds larger apparel

makers, supplying GAP, Wal-Mart, Target, and other major U.S.

retailers. The company has been building factories and textile

mills around the world at record pace recently: Nicaragua,

Indonesia, and now Haiti. One of the largest clothing

manufacturers in the world, a 2009 article reported that its

exports – all to the U.S. – were valued at about $885 million.

“Our 20 factories worldwide produce 1.4 million

pieces of clothing a day and the annual production rate is 360

million pieces,” founder Kim Woong-ki told the Korea

JoongAng Daily. “That number is nearly equal to the U.S.

population.”

But Sae-A Trading is not investing in Haiti to “create

jobs,” as the fans of assembly industry-based “sustainable

development” – like Haitian President Michel Martelly –

claim. The company is moving in to make more money. Sae-A will

be in perfect position to take advantage the

Haiti

Economic Lift Program (HELP) Act

– that allows textiles to enter the U.S. from Haiti tariff-free,

and then of the recently approved US-Korea Free Trade Agreement

(KORUS FTA). Sae-A Trading is setting up shop just in time.

Approved by Congress in October, KORUS FTA – which

could go into effect as early as Jan. 1 – will immediately

reduce tariffs on most Korean goods to zero, with more

reductions coming in five and ten years. A 2007 study by the

U.S. International Trade Commission estimated the agreement “would

likely result in a significant increase in bilateral U.S.-Korea

trade in textiles and apparel, particularly U.S. imports from

Korea.”

And therefore, most likely, a further decrease in

employment in the U.S. textile and apparel sector.

How was

Caracol chosen?

Even

before the earthquake, the GOH and its supporters targeted the

north of Haiti for an industrial park because of its proximity

to the U.S. and to the Dominican Republic. According to various

government and consultant documents, a good site needs access to

a large unemployed population, an abundant water supply,

electricity, and major highways.

The U.S.-based Koios Associates consulting firm,

hired to help choose a site, also noted that the north region

was a great place because “the area has large stretches of

relatively empty land.”

Of course, “relatively empty” is a relative

term, as will be shown below.

The Koios study – dated Sep. 20, 2010 – recommended

18 possible sites, with the Caracol site ranked #2 of 18.

“The river to the east of the site has

substantial perennial flow and is likely to be suitable for

factories using substantial water and requiring discharge of

treated water. The land is devoid of habitation and intensive

cultivation,” the report stated.

Except, it wasn’t quite “devoid.” The Caracol

site was home to 300 farming plots.

But the site was chosen anyway. According to a

subsequent Koios study – dated May, 2011, and entitled “Study

of the Environmental and Social Impacts – Industrial Park of the

North Region of Haiti” – the Caracol site was selected by

the GOH because of:

• the

Trou du Nord River - “it is capable of absorbing a large

volume of treated water,”

• an

abundant subterranean water supply,

• most

of the land belongs to the State, meaning that it would be

easier to kick off the farmers.

“Good

agricultural lands”

In

their second study, Koios admitted that the site was actually

home to “good agricultural lands.” But it was too late by

then. Farmers had been evicted and a fence put up.

Asked after the fact by the Ministry of Environment

(MOE), Caracol Mayor Colas Landry said he disagreed with the

choice of the spot.

“If I were consulted by the project promoters, I

would never propose that site,” he told the MOE in an

internal report leaked to HGW. “I would orient them to

Madras,” a less-used area nearby.

(According to Haiti’s Free Trade Zone Office, Free

Trade and Industrial Zones should not be set up on farming land.

In an interview with HGW, the Office’s Luc Especca insisted on

the point, saying “We all remember what happened with CODEVI.”

The CODEVI Free Trade Zone, built on the fertile Maribahoux

Plain, caused considerable upheaval and protests in Haiti and

internationally.)

What

about the environment?

Shockingly, the second Koios study also admitted that “the

study process and the section of sites was not accompanied by

extensive environmental, hydrologic or topographic research.”

[our emphasis]

Indeed, a comprehensive internal MOE report obtained

by HGW confirmed that, noting that “at [no] moment was the

MOE associated in any thought in the identification of the

Caracol site.”

The report – subtitled “To what extent and under

what prerequisite a win-win situation could be envisaged from an

environmental point of view” – also noted that the PIRN

could have “potentially great adverse impact on the

environment.”

Apparently, the Koios team agreed.

When the firm took a closer look at the site in its

second study this past spring, it suggested the GOH change the “risk

rating” for the project from B, or “medium,” to A

which – according to the MOE document – means “significant

adverse environmental impacts.”

In addition, Koios noted that a more detailed

environmental and social impact would be necessary. The

consultants suggested that while the more thorough study is

conducted, the GOH should “impose certain limits to the

industrial activities authorized in the park during the first 12

to 24 months of operations.”

Koios also noted that the region is also home to the

significant indigenous archeological sites, and some of earliest

European settlements in the hemisphere. The firm went so far as

to make two other, even more radical, suggestions: 1 - Move the

project to another site in the north or even a completely

different region of Haiti, or 2 - Cancel the project, although,

the consultants remarked, “[i]ts cancellation could call into

question the reputation of the parties concerned and could harm

the reputation of Haiti as a country that welcomes investment.”

Not surprisingly, the PIRN was neither moved nor

cancelled.

And, two months after the Koios report came out,

perhaps seeking to downplay the environmental aspect, the

Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) bought several one-page

ads in Le Nouvelliste where it reported that “environment

issues have been considered with a great deal of attention”

and claimed that more studies were underway. A month later, the

IDB’s Eduardo Almeida said everything was ready to move forward

since “[e]nvironmental impact studies… have already been

completed in the region.”

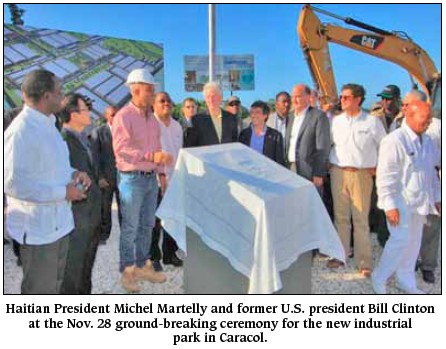

Indeed, the project is moving forward. On Nov. 28,

the major actors flew to Caracol to inaugurate the site.

Clinton, Martelly, Sae-A Trading, the BID – they were all there.

“Haiti is open for business,” Martelly said

as he stood in front of a giant architect’s schematic drawing of

the factory zone. “This is the kind of change we need.”

But what about the risks identified by Koios and the

Ministry of the Environment? Are more studies taking place or

not? Will limits be imposed on the PIRN’s tenants during the

first 12 to 24 months? How did the MEF – the main ministry

shepherding the PIRN and the one that commissioned the Koios

study – react to the Koios recommendations and the MOE report?

Industrial Park in Caracol: A win-win situation?

Why did

the Haitian Ministry of the Environment warn of “potentially

great adverse impact” from the PIRN being built in Caracol

with over $200 million in public and private financing?

Why did the consultants’ study call the nearby

Caracol Bay “unique, productive and precious” and say

that even if all regulations are followed, the PIRN “could

endanger this ecosystem?”

Why did the same consultants – who originally

suggested the Caracol site, but who later admitted they did not

take environmental considerations into account – tell the GOH to

consider moving or even cancelling the project?

These are all relevant and urgent questions.

But even though two extensive environmental and

social impact studies – listing numerous risks – are public and

posted online, and even though there are also several other

studies on the Caracol Bay marine habitat available, no Haitian

or foreign media outlet (except Haiti en Marche) has

looked further than the press releases from the project’s

champions and investors: the U.S. State Department, the IDB, the

GOH and Sae-A Trading.

Instead, the Wall Street Journal, Miami

Herald, Associated Press, Le Nouvelliste,

Haiti Press Network, and others are largely cheerleaders for

the PIRN and the mostly sweatshop wage jobs it will provide.

It comes as no surprise that there are numerous

environmental and social risks associated with any industrial

park – “free trade” or not. But these risks are

exponentially greater in poor countries due to poor zoning, lack

of legislation and/or government control, large unemployed

populations, etc. This does not mean a project should not be

undertaken, but studies should be done and the benefits vs.

risks put before the public.

As noted above, studies were done, including

one released May 13, 2011, by Koios Associates, hired by the MEF

in 2010 and a second one, released on Aug. 5, 2011, and

commissioned by one of the project’s major investors, the IDB.

Both studies have potential conflicts of interest:

Koios chose the site in the first place, and the IDB is donating

or loaning over $50 million for the PIRN. But it appears the

potential conflicts of interest, and the numerous risks outlined

in the documents, were not of significant concern to the

power-brokers. Construction has started and a $15 million power

plant contract was awarded in September.

HGW lacks the space and the human resources to list

all the sources and fully list all the risks, but here are some

of the major ones:

Risk 1

- The Caracol Bay environment

Among

the most obvious risks are the dangers to Haiti’s fragile

environment, specifically the Caracol Bay.

The original, MEF-commissioned study recommending

sites for the PIRN was done by the Koios group, whose 110-page

study identified the Caracol site as #2 out of 18 possible sites

in the north. However, Koios’ own follow-up Environmental and

Social Impact Study, in May, 2011, admitted – shockingly – that

the environment had not been taken into consideration the first

time around.

Also, equally astoundingly, in their impact study,

the Koios team claimed that “It wasn’t possible to anticipate

the presence of the complex and precious ecosystem of the

Caracol Bay before we conducted this environmental evaluation.”

The claim is nothing short of outrageous. The bay –

home to mangrove forests and the country’s longest uninterrupted

coral reef – has been the subject of international study for

some years and is part of several plans to make the region into

a park, according to publicly available documents.

1) A

2009 study for the Organization of American States and the

Inter-American Biodiversity Information Network (IABIN) put the

“value of ecosystem services” of the mangroves and coral

reefs in the bay at US$ 109,733,000 per year.

2) In

2010, the UN Development Program and the Haitian MOE initiated

plans to set up a “National System of Protected Areas (SNAP).”

Over US$2.7 million has been invested in the program already,

according to the MOE. One of the first areas on the list is the

Caracol Bay.

3) The

bay also lies in the Caribbean Biological Corridor (CBC), an

area designated by Dominican Republic, Haiti and Cuba back in

2009, and is part of that US$7.4 million project.

Even if Koios somehow “missed” the literature

on the bay, the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC),

co-headed at the time by Bill Clinton, cannot claim ignorance.

In October, 2010, the IHRC approved $1 million of the CBC’s $7.4

million in funding. That was two months before the

Commission approved the PIRN.

Risk 2

- Water

Another

risk involves water usage and water pollution. The PIRN is

located in the middle of the Trou du Nord River watershed,

identified as a “priority watershed” in a recent study

from the US Agency for International Development.

Water for the PIRN and surrounding settlements will

likely be drawn from the river and the water table. One study

however, by a Washington-based firm commissioned by the IDB,

recommends that water is taken from the water table only because

the Trou du Nord River empties into the fragile Caracol Bay.

Writing in August, 2011, the Environ International Corporation

said: “We strongly recommend using underground waters to meet

the needs of the site.”

But other studies noted that if too much water is

taken from the water table, it could be polluted by salinity due

to an intrusion of saltwater from the Atlantic Ocean.

Over-exploitation of the water table could also harm agriculture

in the region at large, and make it difficult to develop other

water-needy businesses, such a tourism. The Environ group

disagreed, saying there was ample water.

A study by the Louis Berger Group, commissioned by

the MEF and quoted in the Koios study, recommended that water

come from both below ground and from the river. The study said

the PIRN and surrounding population (current and new) should not

use more than 11,000 cubic meters per day. According to the same

study, the park will likely need at least 5,800 cubic meters of

water per day during Phase 1 (2012-2014) and at least 9,800

cubic meters during Phase 2.

(An internal study from the Ministry of Environment

– leaked to HGW – called these estimates “conservative”

and “minimalist,” saying they don’t take into account

continuing deforestation and projected exponential population

growth. More on that study below.)

The other great water-related risk is, of course,

pollution or other negative impact from the use of water from

the river and water table. Here are the main ways water will be

used:

1) For

the textile factory being built by Sae-A Trading Company – A

large amount of water is needed for the manufacturing and dying

processes. There will be significant waste waters needing

multiple treatments.

2) For

cleaning and other processes at the Sae-Trading and other

apparel factories, and possibly for a furniture factory.

(Origins Holdings has been listed in some documents as a

potential tenant).

3) For

the drinking, cleaning and waste treatment needs of workers and

other staff, some of whom will live inside the PIRN confines,

while others live nearby.

4) For

the drinking, cleaning and waste treatment needs arising from

the tens of thousands of new residents the PIRN is expected to

attract to the region.

A waste treatment plant is planned for the park, but

while all of the dye run-off, industrial waste and human waste

can hypothetically be managed with proper treatment, all waste

waters – clean or not – will eventually end up in the Trou du

Nord River and probably the Caracol Bay.

“Even if the wastewater of the park are treated,

there are various other dangers related to the development of

the industrial park on this site which could put the ecosystem

in danger,” the Koios consultants noted.

Water will also be used to cool the electrical plant

being paid for by the U.S. government. The plant - being build

for US$15 million by a Canadian company – will generate

electricity using “heavy fuel oil,” also sometimes called

“bunker fuel.” When dumped back into the Trou du Nord

River, the temperature of water used to cool the turbines must

not be more than 3 degrees centigrade different than when taken

out, or it could have significant negative impacts on aquatic

ecosystems. Needless to say, the use of oil in that fragile

environment also poses a risk.

Risk 3

- Social

The

Koios study estimates that the local population could grow by

between 100,000 and 300,000 people: “Large industrial or

mining projects in poor countries indicate that a large

migration like this could occur, no matter what efforts are

taken to prevent it.”

Other studies put the number of potential migrants

much lower, but even the addition of 10,000 workers and their

family members – 50,000 people – will change the region,

currently home to about 250,000 people, mostly farmers and

fishermen.

Without zoning laws, urban planning, and heavy

police presence, the PIRN might give birth to a new set of

slums. The country has already witnessed the “slumification”

of areas around industrial parks in the capital and in

Ouanaminthe, home to the CODEVI park, and it is likely a similar

process will occur again.

The sudden arrival of thousands can have numerous

negative impacts – more waste, uncontrolled use of water and

trees (for cooking needs), and squatter settlements on farmland

or in environmentally fragile areas. (U.S. tax dollars are going

to be used to build 5,000 homes, but these appear to be slated

for “expatriates” and management.)

Also, the Koios consultants noted: “There is… an

elevated risk of tension between members of local communities

and migrants coming to the region, especially if local residents

feel they don’t have the opportunity to profit from the project,

especially in terms of jobs.”

The Koios study warned that the negative

repercussions of such conflicts might effect factory owners

bottom lines, too. “Local and overseas criticism of the

multinational companies operating in the park, as well as

negative publicity vis-à-vis relations with the local

communities (bringing about costly consumer boycotts, lawsuits,

and other expensive consequences in terms of reputations and

legal risks) are among the greatest consequences of bad

management,” the report says.

Mitigating the risks

Not

surprisingly, despite the risks they identified, the Koios, IDB

and Environ studies all ended up endorsing the project. However,

they also listed numerous steps that need to be taken in order

to minimize or eliminate the risks. For scores of pages, the

consultants outline laws to be voted, programs to be followed,

and constructions that include the immediate creation of a

marine protected area, an extensive 12 to 24 month environmental

study, funding and building infrastructure and housing for the

expected migrants both inside and outside the PIRN, and other

steps.

Koios also optimistically wrote that “if a

sufficient portion of the additional tax revenues are spent on

development and on the improvement of the social and physical

infrastructure in the region, many of these negative effects can

be avoided or diminished.”

Indeed, massive funding could help mitigate risks.

But Koios appears to have forgotten that PIRN tenants – textile

giant Sae-A and other companies – won’t pay any taxes at all for

15 years, meaning that all the “supplementary tax revenues”

will need to come from factory workers, most of whom will earn

little more than $5 a day, who will thus be tax-exempt.

But even if the necessary funding is located, some

critics, including the man currently serving as Environment

Minister, say the recommendations don’t even go far enough.

In his 20-page report assessing the Koios study,

dated Jun. 30, 2011, Joseph Ronald Toussaint said the document

was a positive step but that it underestimated the “magnitude

of impact,” “extent of impact,” “duration of

impact,” and “biophysical changes.”

Then a ministry employee, Toussaint also said that

Haiti’s then Environment Minister was not “associated in any

thought in the identification of the site” [sic] nor in the

terms of reference for the Koios impact study. As noted above,

Toussaint also noted that the water-use estimates were too “conservative.”

Still, Toussaint’s report claimed a “win-win”

situation was possible, if some $54.5 million in studies and

mitigation efforts were implemented.

What did the MEF think of the recommendations and

were they followed? In August and September of 2011, HGW tried

repeatedly to meet with both then-Minister of Economy and

Finance Ronald Baudin, and with Toussaint, and even obtained

promises of interviews from both offices. In the end, however,

both offices refused to speak to journalists.

Maybe the MOE has given up its struggle to protect

the bay? No MOE representative was present at the Nov. 28

inauguration of the PIRN construction site. The environmental

question and the Bay of Caracol were not even mentioned.

What do

Caracol residents think?

Pierre

Renel, like most people in and around Caracol, is a farmer. He

other farmers who lost their crops last January have formed an

association called Association for the Defense of Caracol

Workers (ADTC in French).

“The spot they picked for the industrial park is

the most fertile part of the department,” said Renel,

president of ADTC. “We grow a lot of plantains, beans, corn,

manioc, etc. That’s how families raise their children, educate

their children… its like our ‘treasury!’”

But Renel and other local residents are not opposed

to the park. On the contrary, they are hopeful they and their

children will get some of the jobs officials and consultants

have described. Some local people already have been hired – as

guards or workers at an information kiosk.

According to the PIRN website, all farmers have also

received either land or remuneration for their lost crops or –

if they were owners – the value of their land. While the PIRN

website says all farmers have been paid damages, in a recent

telephone interview, several denied this, saying they were

originally promised land and money. Also, some say they

were not paid the amounts originally promised.

“They told us peasants would get land and cash,

and according to Michaël De Landsheer [of the MEF], landowners

were supposed get US$1200 per hectare, but they are not

respecting their word,” Renel told HGW.

Farmer Robert Etienne is excited about the

factories. “They should have built something like this

already!” he said, his eyes glittering. “Because there’s

no work in this country.”

But Etienne, in his seventies, won’t be one of those

hired. He is too old. Maybe his children will get jobs? Maybe,

maybe not. There will be stiff competition, even with their

sweatshop wages.

Etienne and Renel and others are probably unaware of

the how low salaries will be, and of how the local economy will

likely change as construction moves forward and the factories

start to open up: population explosion, higher rents, a grown in

the “informal sector” and street merchants, lessened

local agricultural production and perhaps even higher food

prices.

As noted earlier, assembly factories with sweatshop

wages are not social projects, despite claims made in the media

and in studies. The Koios study, for example, claims the PIRN

will supply the “means of subsistence to a maximum of 500,000

people, that is 10% of Haiti’s population.”

The claim is very difficult to substantiate. Most

workers will earn a wage that can’t even pay the rent, much less

send children to school.

In the very same study, the authors also offer up

this more honest appreciation: the PIRN “was above all

conceived to facilitate investment in enterprises.”

As previously described, Sae-A and the other textile

factories are moving to Haiti in order to take advantage of

cheap labor, no U.S. tariffs until 2020, a long tax holiday in

Haiti, and proximity to the U.S. market. The PIRN is part of a

global economy predicated on the exploitation of the lowest

wages and a “race to the bottom.”

Are exploitation, potential environmental

devastation and social upheaval really a “win-win”

situation? Is it just to spend US$179 million in foreign public

financing in Haiti, to the possible detriment of workers in

other countries? Can a “new” Haiti really be built on

sweatshop wages and free trade zones?

Haiti Grassroots

Watch is a partnership of AlterPresse, the Society of the

Animation of Social Communication (SAKS), the Network of Women

Community Radio Broadcasters (REFRAKA) and community radio

stations from the Association of Haitian Community Media. To see

images, video and to access links to primary sources - http://www.haitigrassrootswatch.org

. |