|

Troops of the United Nations

military occupation force in Haiti are once again accused of

brutalizing Haitians earlier this month.

Three Haitian men claim they

were savagely beaten by eight Brazilian UN soldiers during the

early morning hours of Dec. 14.

The alleged attack comes only four months

after anti-occupation demonstrations erupted around Haiti

following the release of a cell-phone video showing four

Uruguayan UN soldiers apparently sexually assaulting a young

Haitian man in the southern town of Port-Salut (see Haïti

Liberté, Vol. 5, No. 8, 9/7/2011).

On the afternoon of Dec. 13,

Joseph Gilbert, 29, and Abel Joseph, 20, were on their way to

deliver drinking water when their tanker truck broke down near

Fort Dimanche, a former political prison situated between the

Port-au-Prince shanty-towns of Cité Soleil and La Saline.

The men tried unsuccessfully to

repair the truck during the day. As night fell, they decided to

stay with the truck lest it be vandalized or its water stolen

during the night. To help them to guard the vehicle, they called

on Armos Bazile, the nephew of one of Gilbert’s clients, who

joined them at around 10 p.m..

According to the account the

men gave to the National Human Rights Defense Network (RNDDH)

later that day, at about 3 a.m. on Dec. 14, a patrol of

Brazilian soldiers from the UN Mission to Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH)

passed by them in a military vehicle on a routine patrol. After

passing the tanker truck, the soldiers stopped their vehicle and

walked back to the three Haitians.

“The soldiers arrested them

without any explanation,” the RNDDH wrote in its Dec. 16

report on the incident, which drew on the accounts of the three

men, area residents, witnesses, and the Cité Soleil

Justice of the Peace. “They forced them to empty their

pockets, relieving them of the sum of 4500 gourds [$113 US],

representing the amount of three trucks of water delivered

during the day, and a telephone – [with the number] 39350529 –

belonging to Joseph Gilbert.”

The soldiers also took

Gilbert’s driver’s license and the national ID cards of the two

other men before leading them to the courtyard of the Mixed

Educational Institution of La Saline, a school whose courtyard

is used by area residents to dry clay.

There, the eight Brazilian

soldiers beat the three men “with numerous kicks and punches,”

according to the report. “The victims’ bodies still bear the

visible signs of this physical abuse. They were beaten to the

point where they cannot sit.”

La Saline residents, hearing

the victims’ screams, came out of their homes and told the

soldiers that the men were not intruders and were known in the

area, according to RNDDH investigators, who visited the scene of

the alleged attack.

The soldiers then loaded the

three men into the back of their truck and drove them to a remote

plantain field just outside the city off Route 9. There,

according to the victims, the soldiers stripped the men naked and continued to beat them, even using a machete.

The soldiers then burned the

men’s clothes and drove off, leaving them naked in the field,

the victims said.

The UN has yet to accept

responsibility for the alleged attack on the three men. “MINUSTAH

is doing everything it really can to verify these facts as soon

as possible,” said UN spokesman Farhan Haq, referring to the

RNDDH report during a meeting with reporters at UN headquarters

in New York.

Meanwhile, the UN’s Office of

the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and MINUSTAH’s

Human Rights Section (HRS) investigated and criticized the

Haitian National Police (HNP) for five cases between October

2010 and June 2011 “involving at least 16 HNP officers in the

deaths of eight people,” in a report released this week.

The damning report charges that

“killings are too often justified as a consequence of an

exchange of fire between the police and suspected criminals,”

that “HNP officers directly involved in killings are

protected by their colleagues or superiors,” that official

investigations “are not systematic, are typically slow, and

rarely lead to disciplinary action or a conviction,” that “witnesses

are afraid of the consequences of giving testimony and convinced

that justice will not be rendered,” and that some

foot-dragging “judges choose to delay the investigations.”

As a result, “to date, not a single police officer has been

held criminally or administratively responsible for the deaths

that are the subject of this report,” the OHCHR & HRS

conclude.

Just weeks prior to the Dec. 14

incident and the OHCHR/HRS report, MINUSTAH’s Chilean chief

Mariano Fernandez Amunategui painted a glowing picture of the

mission’s effectiveness in a Nov. 29, 2011 letter to the daily

newspaper Le Nouvelliste.

“Through MINUSTAH’s support

in establishing the rule of law, the HNP’s professionalization

is in good position,” Fernandez wrote. “This has

resulted, with the help of the United Nations Police (UNPOL), in

the strengthening of the HNP’s capacity, through theoretical and

practical training, strengthening of technical and human

capacities, and also the restoration of the HNP’s image among

the population.”

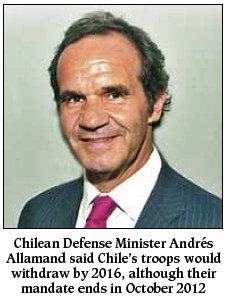

As the Haitian people’s anger

at MINUSTAH grows, so has the frequency of declarations about an

eventual pull-out. This week Chile's Defense Minister Andrés

Allamand announced that his nation would gradually withdraw its

500 troops from Haiti by 2016. The UN Security Council mandate

authorizing MINUSTAH’s deployment only lasts until Oct. 14,

2012. As the Haitian people’s anger

at MINUSTAH grows, so has the frequency of declarations about an

eventual pull-out. This week Chile's Defense Minister Andrés

Allamand announced that his nation would gradually withdraw its

500 troops from Haiti by 2016. The UN Security Council mandate

authorizing MINUSTAH’s deployment only lasts until Oct. 14,

2012.

In September, Brazilian Defense

Minister Celso Amorim announced that his nation would gradually

begin removing is 2,200 troops, the largest contingent in the

force of about 12,500 uniformed personnel, both soldiers and

cops. He set Brazil’s full withdrawal date for 2015.

But most Haitians are not

fooled by the “gradual withdrawal” announcements and want

the UN troops out more quickly. “Recent declarations by

MINUSTAH officials and Latin American ministers are not really

about withdrawal, but rather about how to prolong the presence

of foreign troops in Haiti,” said Yves Pierre-Louis of the

Heads Together of Popular Organizations, a front which has led

many anti-occupation protests. “We want the occupiers out of

Haiti immediately, and certainly not beyond the end of the

current mandate ten months from now.”

MINUSTAH was deployed in Haiti in Jun. 1, 2004,

following the Washington-backed coup three months earlier

against former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. “At the

time, Lula [then Brazilian president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva]

said that the troops would just be needed for six months to

assure a democratic transition,” said Barbara Corrales, a

leader with the Brazilian Workers Party’s O Trabalho

tendency, which organized a large international anti-occupation

conference in Sao Paulo on Nov. 5 (see Haïti Liberté,

Vol. 5, No. 17, 11/9/2011). “But Brazilian troops and

MINUSTAH are still in Haiti over seven years later. The Haitian

people, and indeed the people of the entire continent, are

saying they must get out now.” |