|

Port-au-Prince, February

22, 2012 – Two years after the

earthquake, and despite the proposals written, the consortiums

organized, and the foreign delegations entertained, the

University of the State of Haiti (Université d’Etat d’Haïti or

UEH) still has not seen any “reconstruction,” and the

proposal for a university campus that would unite all 11

faculties remains a 25-year-old “dream.”

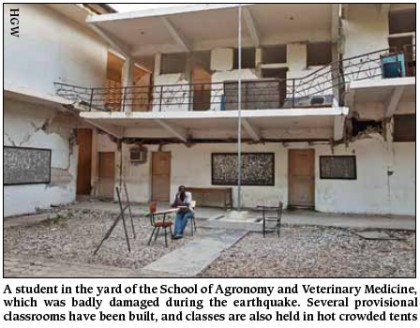

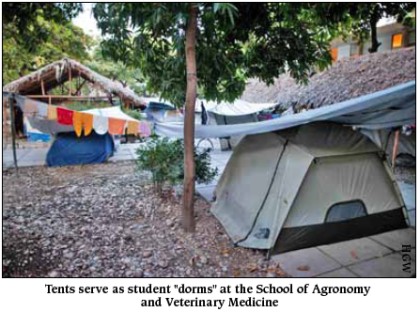

Today, the majority of the

13,000 students at the UEH’s faculties in the capital are jammed

into sweltering sheds, struggling to hear the professor who is

shouting, hoping to drown out the other professors shouting in

the surrounding sheds.

The fact that the Haitian

government and its “friends” have not financed the

reconstruction – and a sufficient operating budget – of the

oldest and most important institution of higher learning in the

country represents more than a “peril” to Haiti’s future.

These choices – or at least, these omissions – offer perfect

examples of the global orientation of the “reconstruction,”

which is centered on the needs of the national and international

private sector, and which favors “quick-fixes” to Haiti’s

urgent problems, rather than lasting solutions over which

Haitians can have some say. Finally, these omissions represent

contempt for the public interests of the entire nation.

The

dream of a campus – The farce of the IHRC The

dream of a campus – The farce of the IHRC

The disaster of Jan. 12, 2010, destroyed

nine of the 11 UEH schools in the capital. Three hundred and

eighty students, and more than 50 professors and administrative

staff of UEH disappeared, according to the university and to

a

study by the Inter-university Institute for Research and

Development (INURED), released in March 2010. (According to the

same study, at least 2,000 students and 130 professors in all of

the institutions of higher learning died in the catastrophe.)

Nevertheless, this tragedy

offered an opportunity to UEH authorities, who are themselves

charged with supervising all institutions of higher learning in

the country. The members of the Council of the Dean’s Office (Rectorate)

saw their chance to make a dream become reality. Twenty-five

years ago, in 1987, delegates at the first conference of the

National Federation of Haitian Students (FENEH) listed a campus

as one of their post-dictatorship goals and demands.

“We always wanted a

university campus, we really struggled for that,” remembered

Rose Anne Auguste in an interview with Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW)

in July 2011. Once a FENEH leader, today she is a nurse and

community activist.

Over one year ago, the Rectorate submitted a proposal to the

Interim Haiti Recovery

Commission (IHRC), the institution charged with approving and

coordinating all reconstruction projects.

“Right in its first

extraordinary meeting, on Feb. 5, 2010, the University Council

decided to face the reconstruction problem… and we voted a

resolution asking the Executive Council to take all measures

deemed necessary to assure all the University faculties could be

rehoused together,” according to the project, which HGW

obtained.

“When considered as part of

the challenge of reconstruction and of the re-founding of this

nation, this project can be seen as a crucial asset of primary

importance which will assure a better tomorrow for our

population,” the same document continues.

The Rectorate proposed a

provisional student and preliminary budget of US$200 million for

the construction of the main campus with classroom buildings,

libraries, laboratories, restaurants, and university residents

to lodge 15,000 students and 1,000 professors on part of the old

Habitation Damien land in Croix-des-Bouquets, north of

Port-au-Prince.

“It’s an old dream,”

said Fritz Deshommes, Vice Rector for Research, during an

interview with HGW.

“It’s really an aberration…

despite the importance of UEH in the higher education system in

Haiti, this prestigious institution has never had a campus,”

he added.

Following the submission of the

project in February 2011, for months, the IHRC “didn’t

respond. We gave a copy to each member of the council… the

administrative director promised to call us, but that promise

was empty,” Deshommes complained. “They never discussed

the proposal.”

Auguste was aware of the

project. Founder of the Association for the Promotion of

Integral Family Health (APROSIFA), she was an IHRC member,

representing (without the right to vote) Haitian

non-governmental organizations.

“The project was never

discussed at any IHRC assembly, but every member knew about it,”

Auguste told HGW. “I tried to pressure the administrative

council to get the project considered and discussed.”

“According to the project

director, there were some technical weaknesses,” she added.

Maybe. But the IHRC had its own

weaknesses, according to

a study by the U.S. Government

Accountability Office (GAO) , published in May 2011.

After a year of existence, many

projects had been approved but not financed; two out of five

departments had no director, and 22 of 34 key posts remained

vacant, the study noted.

In short, the IHRC was not “yet

fully operational… According to U.S. and NGO officials, staffing

shortages affected the project review process — a process to

determine whether project proposals should be approved for

implementation — and communications with stakeholders, such as

the Board of Directors,” the GAO study noted.

But the IHRC did acknowledge

getting the project. Contacted via email on Oct. 17, 2011 by HGW,

IHRC Director of Projects at the time, Aurélie Baoukobza,

promised that the campus proposal was under consideration.

“The proposal is currently

following the reviewing circuit and the discussions relative to

its approval have not yet been shared,” she wrote.

“Therefore, I cannot discuss

this project with the media. The decision of the IHRC and the

Government are supposed to be delivered to the submitting

parties by the end of the week. Only after that official email

can I speak about the project,” she promised.

Four days later, on Oct. 21,

the mandate of the IHRC expired. There ensued silence.

Many years of struggle

Deshommes was not surprised at the silence,

or at the lack of a campus.

“The reason that the

university campus has never built is political,” he said.

“Because, if all the students were permanently together in one

place, they would have the necessary material conditions to

better organize themselves and make their demands heard. Then,

they would be able to turn everything upside down. The political

authorities understood the importance of this. A single campus

is not in their interests.”

As noted above, and not

surprisingly, the fight for a campus didn’t start only after the

earthquake. As Auguste said, it was born after 1986, the date of

the end of François and Jean-Claude Duvalier’s dictatorship.

Ever since a 1960 strike of

students at the University of Haiti, François Duvalier

established his control over the various faculties. He issued a

decree on Dec. 16, 1960, creating the “University of the

State” in the place of the University of Haiti. The decree’s

fascist character was apparent in the various lines. One reads

in the decree that Duvalier was “considering the necessity to

organize the University on new foundations in order to prevent

it from transforming into a bastion where subversive ideas would

develop…”

Article 9 was even clearer. It

noted that any student wanting to enroll in the university had

to get a certificate from the police that he or she did not

belong to any communist group or any association under suspicion

by the State.

After Feb. 7, 1986 – the

departure of Jean-Claude Duvalier in a US-government chartered

airplane – one of the most dominant slogans was “Haiti is

free!”

The political uprising that

spread throughout the country extended to the university system.

Professors and students demanded a number of reforms as well as

the construction of a campus that would gather together all the

faculties sprinkled throughout the capital.

Since then, there has been some

progress – the name was changed to UEH, there has been some

democratization, the level of teaching has been improved – but

lack of financing has paralyzed the institution. The budgets

from the last few years show that UEH has never received more

than 1 to 1.3 % of the state budget.

Even worse, the government’s

Action Plan for Reconstruction and Development (PADRN), proposed

by former President René Préval’s team, asked for only US$60

million for “professional and higher education” out of a

total request for $3.864 billion sought for reconstruction –

only 1.5% of the total.

President Michel Martelly’s

government indicated that it would increase UEH’s budget but –

according to a recent

report by AlterPresse, a member of the HGW

partnership – the most recent budget dedicates only 1.5% to UEH.

“This budget shows the

contempt that our elected officials have for the country’s

principal public institution of higher education, as well as

their evident desire to weaken it and perhaps even do away with

it altogether,” Professor Jean Vernet Henry, the UEH Rector,

told AlterPresse in the Jan. 27 article.

“A race between education and

catastrophe”

The low funding represents much more than

contempt. It represents a danger, a “peril,” according to

experts.

A 2000 study funded by the

World Bank –

Peril and Promise: Higher Education in

Developing Countries – sounded the alarm about the lack of

investment in public higher education over 10 years ago.

“Since the 1980s, many

national governments and international donors have assigned

higher education a relatively low priority,” the study says.

“Narrow — and, in our view, misleading — economic analysis

has contributed to the view that public investment in

universities and colleges brings meager returns compared to

investment in primary and secondary schools… As a result, higher

education systems in developing countries are under great

strain. They are chronically underfunded, but face escalating

demand—approximately half of today’s higher education students

live in the developing world.”

The study looked at enrollment

and investment figures in countries around the world (figures

from 1995). Here are some extracts, compared with Haitian

figures calculated by Haiti Grassroots Watch.

|

|

Haiti* |

Dominican Republic |

Nicaragua |

Latin America and Caribbean |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

|

Higher education enrollment for

university age group |

1% |

22% |

12% |

18% |

3% |

|

Percentage of state budget

dedicated to education |

14% |

13.2% |

N/A |

18.1% |

15.2% |

|

Percentage of that amount going to

higher education |

8.25% |

9% |

N/A |

19.5% |

16.7% |

* Note – The Haiti budget figures

reflect an average of the 2008-2009 and 2009-2010 fiscal year

actual expenses.

Not surprisingly, in terms of enrollment,

Haiti is far behind its neighbors, and in terms of investments,

Haiti is at the bottom of the list. Even the Dominican Republic,

well known for its failure to invest in higher education, is

ahead of Haiti.

The authors of the study – a

committee of academics and former ministers headed by the

ex-Dean of Harvard University and the Vice Chancellor of the

University of Cape Town – cited a warning from H.G. Wells.

“The chance is simply too

great to miss,” they wrote. “As H.G. Wells said in The

Outline of History, ‘Human history becomes more and more a

race between education and catastrophe.’”

The “friends of Haiti” support the

private sector

At the very moment the proposal for the

State University of Haiti’s new campus was locked in a drawer,

the Dominican government built a university campus in Haiti’s

north – the King Henry Christophe University. Built in only 18

months, the campus cost US$50 million.

And the universities and

governments of the countries that call themselves the “friends

of Haiti”?

Despite a number of

meetings

and conferences held at seaside hotels and at the most expensive

conference centers in the country, despite the

promises of a

number of U.S. universities, through at least

two

consortia, and despite the promises at the

Regional Conference of Rectors and Presidents

of the Francophone

University Agency (AUF), as well as

AUF itself… most UEH courses are still taught in

sheds and temporary buildings.

“We have hosted a lot of

universities who are capable of assisting us, but they don’t

have the resources to build,” Rector Henry told the magazine

Chronicle of Higher Education in

an article published

last January.

“They can [only] only help

us through long-distance courses, scholarships and exchanges,”

he added.

Meanwhile, at Quisqueya

University, a private institution, reconstruction is moving

along well. Back in October, the IHRC gave a green light for a

project of the Faculty of Medicine, and more recently – last

December – the Clinton Bush Fund offered US$914,000 for a “Center

for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.”

“The Center will be a

destination for business people of all levels,” the Fund’s

Paul Altidor said in

an article on the Fund’s website.

The focus of Haiti’s “friends”

is clear.

The future in peril

But the World Bank’s “Peril and Promise”

study is also clear on the necessity to invest in public sector

higher education.

“Markets require profit and

this can crowd out important educational duties and

opportunities,” the study says. “The disturbing truth is

that these enormous disparities are poised to grow even more

extreme, impelled in large part by the progress of the knowledge

revolution and the continuing brain drain… For this reason the

Task Force urges policymakers and donors – public and private,

national and international – to waste no time. They must work

with educational leaders and other key stakeholders to

reposition higher education in developing countries.”

And that was in 2000.

Have Haitian politicians,

donors, “citizens” in the north, and others trying to

take over the King Henry Christophe University read that report?

Haiti’s past and present

governments – who permitted in the past and permit today the

deterioration and denigration of a commonly held asset, the

State University of Haiti – have they been so completely swept

away by the flood of neoliberal thinking that they don’t see the

catastrophe that they are creating through not

reconstructing the UEH?

Maybe they should go back to

school and learn more about the notion of common property,

so

well described recently by Professor Ugo Mattei. Or to read the

study by the World Bank, usually a bastion of neoliberal

ideology.

Because, if H.G. Wells were in

Haiti today, he would surely agree that, in the hemisphere’s

second oldest republic, “catastrophe” has been ahead of “education”

for a long time.

Students from the Journalism Laboratory

at the State University of Haiti collaborated on this series.

Haiti Grassroots Watch is a partnership

of AlterPresse, the Society of the Animation of Social

Communication (SAKS), the Network of Women Community Radio

Broadcasters (REFRAKA) and community radio stations from the

Association of Haitian Community Media.

To

see other images -

http://www.haitigrassrootswatch.org |