|

The sudden Feb. 24

resignation of Haitian Prime Minister Garry Conille is just the

latest episode in a sharpening class struggle for political

power between three sectors: Washington, the neo-Duvalierists,

and the Haitian masses.

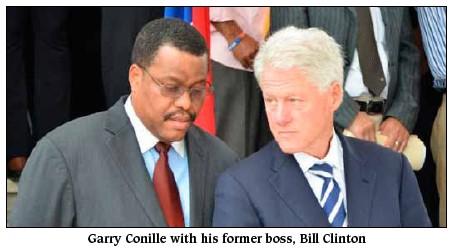

Conille, a medical doctor and

formerly one of UN Special Envoy to Haiti Bill Clinton’s chiefs

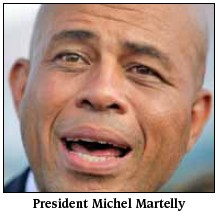

of staff, was imposed as Prime Minister on President Michel

Martelly last October by Washington. He was a “technocrat”

similar to his immediate predecessor, Jean-Max Bellerive, former

President René Préval’s last prime minister. Both men are

knock-offs of Bellerive’s mentor, Marc Bazin, a former World

Bank economist who was imposed as Finance Minister on

Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier in 1982. Washington had

sent Bazin – dubbed at the time “Mr. Clean” – to rein in

rampant Duvalierist corruption, which was siphoning off, into

Swiss bank accounts, millions of dollars from U.S. and

international financial institution (IFI) aid packages sent to

build infrastructure to service North American corporate

interests, principally cheap-labor assembly industries. But,

after only six months of house-cleaning, Bazin was forced to

resign, much like Conille.

Martelly’s clique – whose

chefs de file are Foreign Minister Laurent Lamothe and

Interior Minister Thierry Mayard-Paul – represents a resurgent

neo-Duvalierist sector, which has a different agenda than the

servile technocrats. They seek to establish Haiti as a

sort of chasse gardée for their

business interests and corruption, rejecting oversight by

Washington and the IFIs. This was the model of their fathers,

who were by and large prominent Duvalierists, the political

representatives of Haiti’s grandons, or big landowners.

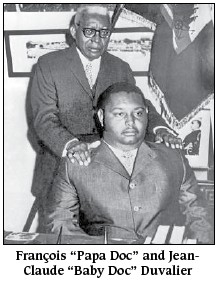

François “Papa Doc” Duvalier

and his son often had a prickly relationship with Washington

during their 29 year dictatorship (1957-1986), not because of

any progressive tilt, but because their economic base – the

grandon class, as direct exploiters of the peasantry – was

independent of, and to some extent in conflict with, U.S.

capitalist interests.

Although Washington facilitated

Papa Doc’s electoral victory in 1957 (just as it did Martelly’s in 2011), Papa Doc – a student of Machiavelli’s

handbook on political intrigue, The Prince – began to

veer away from Washington’s control soon after coming to power.

In 1962, Washington sent a

small U.S. Marine force to exercise, train, and beef up the

Haitian Army (which had been its proxy since the end of the

1915-1934 U.S. military occupation) in an effort to intimidate

and reassert control over their unruly pawn. Instead, Duvalier

used the military aid to reinforce his Volunteers for National

Security (VSN), better known as the “Tonton Macoutes” or

Uncle Knapsack, a folklore figure who carries off children in

the night. Duvalier subdued the Haitian Army (later Macoutizing

it) and expelled the U.S. troops, earning him the enmity of the

Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

In 1962, Washington sent a

small U.S. Marine force to exercise, train, and beef up the

Haitian Army (which had been its proxy since the end of the

1915-1934 U.S. military occupation) in an effort to intimidate

and reassert control over their unruly pawn. Instead, Duvalier

used the military aid to reinforce his Volunteers for National

Security (VSN), better known as the “Tonton Macoutes” or

Uncle Knapsack, a folklore figure who carries off children in

the night. Duvalier subdued the Haitian Army (later Macoutizing

it) and expelled the U.S. troops, earning him the enmity of the

Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

Papa Doc and, to a slightly

lesser extent, his son assumed a faux nationalist stance, in

essence telling Washington that they were in charge of this

neo-colony (although they’d share the spoils for a price) and

would run it as they saw fit. The result was an uneasy alliance,

because Washington needed and valued the Duvaliers’ fierce

anti-communist purges and posture as a bulwark against the

revolution in neighboring Cuba.

Martelly is trying to replay

some of Duvaliers’ tactics, working to re-establish the

Macoutized Army and flirting with the Venezuela-led ALBA

alliance, much as Papa Doc would get his way by threatening

Washington that he might ally with Cuba. (An ALBA meeting is

scheduled to take place in Jacmel on Mar. 2-3).

Washington and its allies

stopped short of publicly scolding Martelly for Conille’s

removal but made their strong disapproval clear. The U.S.

Embassy bemoaned the loss of Conille’s “perspicacity and

energy” which he “devoted to the betterment of the

Haitian people’s living conditions.” Canadian Foreign

Minister John Baird said that “Canada deeply regrets”

Conille’s resignation, which meant the loss of “a competent

leader, a friend of Canada, and a man who embodies hope,”

saying it would “increase instability” in Haiti. UN

Secretary General Ban Ki-moon expressed “concern” about

the resignation, while the Chilean head of the UN Mission to

Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH) Mariano Fernández Amunátegui said

that “the resignation of Dr. Garry Conille shows,

unfortunately, that rifts have overtaken reconciliation to the

detriment of the country.”

Pastor Edouard Paultre of the

Haitian Council of Non-State Actors (CONHANE) is an unofficial

Haitian mouthpiece of “the international community.” He

expressed more forthrightly what the diplomats did not. “The

Prime Minister resigned because of big cases of corruption,”

he said. “We are faced with a power which does not really

want to fight corruption in the country.”

Meanwhile, the Haitian masses

watch the spectacle of this imperialist/Duvalierist rivalry with

a combination of glee and dread, fearing the repression which

may be unleashed. Haitian grassroots groups have held

demonstrations and press conferences several times weekly to

denounce, among other things, the continuing UN military

occupation of Haiti, the relaunch of the Haitian Army (which is

informally training and rearming in camps nationwide), and

Martelly’s non-prosecution of Baby Doc for crimes against

humanity (the former “President for Life” has been back

in Haiti since January 2011).

On Feb. 17, just before Carnival, students

clashed with pro-Martelly goons when the president crashed an

international conference at the State University’s Ethnology

School. Several students were wounded and arrested, while the

goons smashed car windshields and university property.

The fiercest attacks dogging

Martelly are being led by Senator Moïse Jean-Charles, a

firebrand former peasant organizer allied with former President

Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s Lavalas Family. Despite Aristide’s

extremely low public profile since his return from a seven-year

exile last March (he has never even left his home), the party

remains, 16 years after its founding, the foremost political

voice and hope of the Haitian masses.

Moïse, along with a growing

alliance of parliamentarians,

has charged Martelly, his family,

and his clique with a wide array of corrupt practices, from

$20,000 per diem expense accounts on frequent trips to the

brazen embezzlement of funds for phantom projects from the state

bank (see Haïti Liberté, Vol. 5, No. 25, 1/4/2012).

But Moïse’s most persistent,

and politically lethal, charge is that Martelly is (or was) a

U.S. citizen, which, if true, would be a flagrant violation of

the 1987 Haitian Constitution and open the president up for

impeachment.

Last week, Moïse wrested back

control of the Senate Commission investigating Martelly’s

nationality (and that of 39 other high government officials)

from two Martelly allies – Senators Joseph Lambert and Youri

Latortue – who had been impeding the investigation.

Martelly has been infiltrating

former Army officers, policemen, and death-squad paramilitaries

into the state intelligence and security apparatus, while

assembling in Florida a “hit team” to eliminate

troublesome parliamentarians, according to one inside source

(see Haïti Liberté,

Vol. 5, No. 31, 2/15/2012).

The volatility of this

three-way scrimmage was evidenced this week when rumors began on

Feb. 25 that the Martelly government had issued a warrant to

arrest Aristide and eight others on a collection of corruption

and drug trafficking charges that were concocted in 2004 by the

post-coup de facto regime. Popular outrage was swift and loud.

Radio call-in shows were dominated by irate listeners, and the

giant Port-au-Prince slum of Cité Soleil saw hundreds mobilize

on the night of Feb. 27. That same evening, the Justice Ministry

issued a “formal denial” of the “fanciful rumors”

that the government had issued warrants for Aristide’s arrest.

While Washington and the neo-Duvalierists

have their differences, they agree on one thing: the Haitian

masses in general, and the Lavalas Party in particular, must not

hold political power. This is where the danger lies.

If Sen. Moïse and his

parliamentary allies are successful in dislodging Martelly

(which might only push the besieged president to use the

repressive forces he’s arrayed), it might lead to early

elections, which the newly reorganizing Lavalas Family could be

well positioned to win, as they’ve won all electoral contests in

which they’ve ever participated. (The party had been banned from

elections since the 2004 coup.)

Herein lies Washington’s

dilemma: should it help to push out an increasingly mercurial

Martelly if it might set the stage for the Lavalas Family, and

the Haitian masses, from regaining some measure of political

power?

The U.S. may have hoped that

Martelly would publish Haiti’s amended Constitution (as Conille

and Paultre had urged), whereby the Prime Minister would assume

the Presidency in the event of a presidential vacancy (the

Supreme Court head steps in under the 1987 charter). But now

Conille is out of the picture (although he remains acting PM

until his replacement is named). Martelly has proposed three of

his closest aides to fill the post: Lamothe, Mayard-Paul, and

Anne Valérie Timothée Milfort, his appointee to the Interim

Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC). That agency, which was

co-headed by Bill Clinton, saw its mandate expire in October,

and it has not been renewed, another neo-Duvalierist foot-drag

that irks Washington.

Finally, MINUSTAH, the

principal enforcer of Washington’s agenda in this high-stakes

political game, sees its existence threatened. UN officials have

said they need until 2016 to create a “secure and stable

environment” in Haiti. However, the neo-Duvalierists want to

supplant the UN troops with their own Macoutized force, while

the Haitian masses want UN troops out immediately, principally

because in October 2010 UN Nepalese troops inadvertently

imported cholera, starting an epidemic which has now killed over

7,000 and sickened over half a million. There are also almost

monthly cases of UN soldiers sexually assaulting Haitian minors,

all of which have gone unprosecuted.

MINUSTAH’s increasingly tenuous position

and Martelly’s increasingly erratic behavior prompted the entire

UN Security Council to make an unprecedented visit to Haiti

from Feb. 13-16. Tellingly, the delegation was led by U.S.

Ambassador to the UN Susan Rice rather than (as protocol would

dictate) the Council’s President, who during February was the

Togolese Ambassador.

Haiti has seen this troubled

scenario before. In 1986, Washington helped push Baby Doc out of

power, confident that it could buy ensuing elections and insert

their chosen candidate, Marc Bazin, in the presidency.

Untarnished elections couldn’t be held until 1990, when the

technocrat Bazin’s main opponent appeared to be a feared

Duvalierist and former leader of the Tonton Macoutes, Roger Lafontant, who was later disqualified. Washington thought it had

the election in the bag.

But the strategy foundered when

a parish priest from a Haitian slum, Father Jean-Bertrand

Aristide, entered the race at the last minute, winning with 67%

of the vote against Bazin’s 14%, despite being outspent by a

factor of 72 to one.

In short, Washington learned

the hard way the meaning of the Haitian proverb, Ayiti se tè

glise. Haiti is slippery ground. |