|

Haiti’s

former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide “is once again in the

crosshairs of the U.S. government,” reported the Miami

Herald on

Mar. 3, “this time for allegedly pocketing

millions of dollars in bribes from Miami businesses that

brokered long-distance phone deals” with TELECO, the once

state-owned phone company. (TELECO was privatized in 2010.) Haiti’s

former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide “is once again in the

crosshairs of the U.S. government,” reported the Miami

Herald on

Mar. 3, “this time for allegedly pocketing

millions of dollars in bribes from Miami businesses that

brokered long-distance phone deals” with TELECO, the once

state-owned phone company. (TELECO was privatized in 2010.)

The Herald’s writers got

a little carried away. They were working from a U.S. indictment

charging that a certain Haitian “Official B” – whom the

Herald and a defense lawyer deduce, but cannot confirm,

is Aristide – made off with about $1 million, not “millions.”

But the whole story stinks to

high heaven. Aristide’s accuser is one of those indicted,

Patrick Joseph, 50, TELECO’s former director. Aristide fired him

in 2003 for corruption, a key fact never mentioned in any of the

Herald’s reports. Is it surprising that Joseph or his

lawyer might now accuse Aristide as an accomplice, especially

given the incentives U.S. prosecutors are surely offering him?

Washington’s campaign to pin

something – anything – on Aristide has long been known. About

2000 secret U.S. State Department cables obtained by the media

organization WikiLeaks and then provided to Haïti Liberté

provide one of the best confirmations of the U.S. witch-hunt.

Some of the cables, not

previously published by Haïti Liberté, show that in

recent years the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Technical

Assistance (OTA) gave hundreds of thousands of dollars in

funding as well as “monthly training and technical assistance”

(according to a

Jul. 25, 2008 cable) to Haitian agencies like

the Central Unit for Financial Investigation (UCREF). Prime

Minister Gérard Latortue’s de facto government formed UCREF to

find evidence of and make a case for corruption under Aristide’s

government, which was overthrown in a Feb. 29, 2004 coup d’état

supported by Washington.

A

Jan. 17, 2008 cable

notes

that the OTA trained UCREF in a program costing the U.S. taxpayer

$350,000 over two years “to improve investigation and

prosecution of financial crimes,” i.e. to find something on

Aristide.

Despite such U.S. support, UCREF could never build a credible case. Even a civil suit based

on UCREF’s 69-page report against Aristide, brought in a Miami

court in November 2005, was abandoned by the lawyers filing it

after a few months when they saw that it was going nowhere. Why?

Because there was no evidence.

Ironically, UCREF’s chief,

Jean-Yves Noel, was himself briefly jailed by a Haitian judge

for kidnapping. He gave a “a rambling, emotional and

sometimes confusing account” of his arrest to U.S. Embassy

officials and “Treasury investigators,” reported U.S.

Ambassador to Haiti Janet Sanderson in a

Jun. 1, 2006 cable

marked “Confidential.”

Noel claimed there were two

attempts to assassinate him while he was imprisoned from May

22-29, 2006.

“Noel’s story should not

necessarily be taken at face value,” Sanderson opined. “His

cooperation with USG [U.S. Government] investigators, always

spotty at best, deteriorated severely over the past 6 months for

a variety of reasons that arouse our suspicions. Many claim that

Noel is corrupt and his arrest was payback for past corruption.”

Undeterred, Sanderson

recommended that “We need to be careful to separate Jean-Yves

Noel, the individual, from the work of UCREF, the institution,”

arguing that “we need to continue to support the work of the

fledgling anti-corruption office” even though “corruption

is entrenched in Haitian society and political interference the

norm.” Of course, Sanderson was not referring to the

political interference of her own embassy.

On the evening of Mar. 6, 2012,

two days after the Herald’s story, gunmen on two

motorcycles fatally shot in the mouth Venel Joseph, 80, as he

was returning to his home in Port-au-Prince. He was the father

of Patrick Joseph and, under Aristide from 2001 to 2004, had

been the director of Haiti’s Central Bank, which the indictment

alleges distributed the bribes paid by the U.S.-based telecoms.

The Miami Herald and the

Wall Street Journal, historically the two principal

vectors of Washington’s version of events in Haiti, immediately

implied that Aristide was behind the killing.

“The shooting of Venel

Joseph at the wheel of his car looks more like a hit job,”

wrote Mary Anastasia O'Grady, for years the Wall Street

Journal’s point-person for attacks on Aristide. Since

Patrick Joseph “according to Herald sources, has fingered”

Aristide, O’Grady reasons, he “could be the best hope that

Haitians have of getting to the truth about Mr. Aristide and his

American business partners. But sources say the former Teleco

executive still has relatives in Haiti. If he fears for them, he

could clam up. That would be one explanation for his father's

murder.”

But Aristide’s long-time lawyer

Ira Kurzban took another view. “To me, Venel Joseph’s killing

bears all the markings of a U.S. intelligence community hit,”

he said. “First, they eliminate someone who might contradict

and discredit the charges of corruption against former President

Aristide presently being attributed to his son, Patrick Joseph.

Secondly, they smear Aristide, trying to make it look like he’s

behind it. Lastly, the killing might push Patrick Joseph to make

other allegations against Aristide in a desire to avenge his

father.”

In 2003, Aristide moved

forcefully against Patrick Joseph when he got wind of corruption

at TELECO. “We are fighting corruption,” Aristide

declared when he made a surprise visit to TELECO’s

Port-au-Prince headquarters on Jun. 19, 2003. “Nobody at

TELECO would be happy to be laboring away while they see other

people bathing in corruption. And that is why, we are fighting

corruption in TELECO and in the state as a whole. And if there

are private individuals who are bathing in corruption and who

want to corrupt people in TELECO, that also is no good.”

Four days later, on Jun. 23,

2003, Patrick Joseph was dismissed from his post. Rather than

applaud Aristide’s moves against corruption at TELECO, the U.S.

seeks to portray Aristide as behind it. Meanwhile, Joseph has

confessed to taking kickbacks.

“In the end, there is not a

shred of evidence in the indictment that Aristide did anything

corrupt except uncorroborated testimony of a person who is an

admitted corrupter and criminal,” Ira Kurzban concluded.

The campaign to prosecute

Aristide for corruption, in an attempt to politically neutralize

him, has been going on for years. In a

Jul. 25, 2008 Embassy

cable, Chargé d’affaires Thomas Tighe wrote that the OTA wanted

then President René Préval’s “cooperation with the USG in

moving cases involving telecommunications companies with

reported ties to Aristide to prosecution in the United States,”

and that the “OTA team advised Préval that a criminal

case is close to indictment in the U.S. but U.S. prosecutors

were requesting Teleco officials' immediate assistance in

providing certain documentation.” But now, almost four years

later, the U.S. prosecutors still have no documentation or other

evidence, only the testimony of Patrick Joseph.

“The US government has spent

millions, possibly tens of millions, of dollars trying to

railroad Haiti's former president,” wrote Mark Weisbrot of

the Washington-based Center for Economic and Policy Research in

the

Guardian on Mar. 13. “On behalf of US taxpayers,

we could use a congressional inquiry into this abuse of our tax

dollars. It also erodes what we have left of an independent

judiciary to have federal courts in Florida used as an

instrument of foreign policy skullduggery.”

Thousands marched in

Port-au-Prince on Feb. 29, the coup’s anniversary, cheering

Aristide and lambasting Haiti’s current neo-Duvalierist

president Michel Martelly.

“The display of popular

support for Aristide is very worrisome to the U.S., so indicting

Titid [Aristide] before a potential comeback makes perfect

sense,” said Robert Fatton, a Haitian-born professor at the

University of Virginia who has written several books on Haiti,

to the Miami Herald.

As Weisbrot then notes, “It

makes even more sense if you look at what the US government – in

collaboration with UN officials and other allies – has been

doing to Aristide since they organized the 2004 coup against

him.” For example, Edmund Mulet, the head of the UN’s

military occupation force called MINUSTAH, had advice for

Assistant Secretary of State Thomas Shannon in a Jul. 25, 2006

meeting in Port-au-Prince, an Aug. 2, 2006 WikiLeaked

cable

reveals. Among other things, Mulet "urged US legal action

against Aristide to prevent the former president from gaining

more traction with the Haitian population.” That “legal

action” is what we’re seeing today.

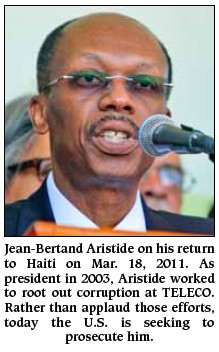

Although Aristide has studiously maintained a low profile since

his return to Haiti last Mar. 18 from a seven-year

Washington-enforced exile in South Africa, he remains a

political symbol that stirs the passions and courage of Haiti’s

masses. Washington’s clumsy and transparent attempts to

discredit him have always served to only increase his appeal,

not diminish it. |