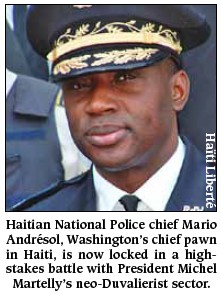

|

First, President Michel Martelly got rid of

Prime Minister Garry Conille in February. Now, he is trying to

fire the Director General of the Haitian National Police (HNP)

Mario Andrésol. But the police chief is refusing to step down.

The showdown for control of

Haiti’s only official armed force, and the crux of state power,

is part of a larger, complex class struggle between three

sectors: Washington, Martelly’s neo-Duvalierists, and the

Haitian masses.

Andrésol is a key pawn of

Washington on Haiti’s political chessboard, as was Conille (see

“Class Analysis of a Crisis: What Lies Behind PM Conille's

Resignation?” in Haïti Liberté, Vol. 5, No. 33,

2/29/2012). Since becoming Haiti’s police chief in 2005, he has

been viewed by Washington as “trustworthy,” according to

numerous secret U.S. State Department cables obtained by the

media organization WikiLeaks and provided to Haiti Liberté.

Martelly’s sector, which came

to power through an illegal March 2011 election, is not considered

trustworthy. The new president borrows inspiration, officials,

and tactics from the dictatorships of Presidents “for life”

François and Jean-Claude Duvalier (1957-1986). Martelly’s

principal gambit today is to reconstitute a repressive force

similar to the Duvalier’s Volunteers for National Security (VSN),

better known as the Tontons Macoutes. Toward this end, he has

tolerated (and some reports say organized) the re-arming of

former and would-be soldiers and paramilitaries now occupying

several former Haitian Army bases around Haiti. Remobilization

of the Haitian Army, disbanded by former President Jean-Bertrand

Aristide in 1995, was one of Martelly’s campaign promises.

On street corners and radio

shows, Haitians now express their apprehension about Martelly’s

embryonic but still unofficial “Pink Army” (lame wòz), a

reference to the color of Martelly’s campaign posters.

Washington, along with its

junior partners France and Canada, also opposes reestablishment

of the Haitian Army (Forces Armées d’Haïti or FAdH), because the

force would not be under its control as are the HNP and the

9,000 foreign military occupation troops known as the United

Nations Mission to Stabilize Haiti or MINUSTAH.

Following Conille’s forced

resignation on Feb. 24, Andrésol, 51, is the last high-ranking

Haitian official who is loyal to Washington’s agenda of making

Haiti a thoroughly obedient neocolony. He began his career as a

Haitian Army captain with posts in the Traffic corps and at the

Port-au-Prince airport. After the FAdH’s dissolution, he joined

the Interim Police Force, becoming close to its chief Dany

Toussaint, and later he became an HNP police chief in

Pétionville.

Under the first administration

of former President René Préval (1996-2001), Andrésol became a

protégé of Robert “Bob” Manuel, the Secretary of State for

Public Security, and was soon promoted to the chief of the

Central Direction of the Judiciary Police (DCPJ), the third most

powerful police post. There, he worked closely with U.S.

officials, particularly those of the U.S. Embassy’s Narcotics

Affairs Section (NAS).

Aristide took office for a

second time in February 2001. In August 2001, Aristide’s

government arrested Andrésol, alleging that he was involved in a

deadly Jul. 28, 2001 attack on Haiti’s Police Academy and two

police stations, in which at least eight cadets and policemen

were killed. It was the first incursion by the so-called “rebel”

force based in the Dominican Republic and headed by Guy

Philippe, another former soldier and police chief whom Andrésol

worked with closely under Bob Manuel.

But the U.S. government

intervened after Andrésol was detained. The Los Angeles Times

wrote a Aug. 24, 2001 piece that decried Andrésol’s arrest,

calling him “a super-cop” and “a rare Haitian hybrid

of Frank Serpico and Eliot Ness.” Soon, Andrésol was freed,

going into exile in Miami.

He would soon be recalled to

service. After Philippe and his “rebels” succeeded, with the

help of U.S. Special Forces, in overthrowing Aristide on Feb.

29, 2004, Washington installed the government of de facto

Prime Minister Gérard Latortue. In mid-2005, Latortue brought

Andrésol back to Haiti as the HNP’s Director General (DG) to

whip into shape the force, which had been ineffective and

faltering in the face of stiff popular resistance to the 2004

coup d’état. WikiLeaked U.S. Embassy cables show that the

appointment delighted Washington.

Andrésol “has proved himself

committed to radical overhaul and reform of the HNP, and we have

no reason to believe he will not continue to fully support

critical aspects of international oversight, especially vetting

and certification of HNP officers,” gushed a Mar. 8, 2006

“Confidential” dispatch from Embassy Chargé d’Affaires Douglas

Griffiths.

Washington was not just the HNP’s overseer, but its paymaster. “Our role in supporting

the HNP... remains central,” explained Chargé d’Affaires

Thomas Tighe in a

Nov. 3, 2006 cable. “[O]ur material support

for the HNP, which ranges from arms and ammunition to the

uniforms on their backs and the food their cadets eat at the

academy, is the critical factor enabling the HNP to assume

greater responsibility for basic security and to even

contemplate utilizing MINUSTAH resources in implementing more

ambitious reform.”

Above all, Tighe concluded, “we

are heartened by the commitment of DG Andrésol... to reform the

HNP, attack corruption, and re-establish law and order

throughout Haiti.”

In a Nov. 3, 2006 meeting with

President Préval, his Prime Minister, his Justice Minister,

Andrésol, and U.S. Embassy officials, Anne W. Patterson, the

Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Bureau of International

Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) “highlighted the

importance of the USG [U.S. government] assistance to the police

and praised the leadership of DG Andrésol,” reported U.S.

Ambassador to Haiti Janet Sanderson in a Nov. 13, 2006 secret

cable.

Andrésol earned this praise by

working closely with the U.S. and the MINUSTAH in organizing the

crackdown on popular resistance cells to the coup and occupation

(called “gangs” by the Embassy) in Cité Soleil, particularly the

deadly joint MINUSTAH/HNP assault of Dec. 22, 2006. In her Dec.

21, 2006 cable about the operation, Sanderson concluded: “Decisive

action against the gangs will also hopefully, three years after

Aristide's departure, allow the international community and the

GoH [Haitian government] to make good on promises to deliver

assistance to the most needy of Haiti's poor.”

Furthermore, “Andrésol

enthusiastically welcomed” among other things “the

possibility of more U.S. police officers coming to MINUSTAH to

assist the HNP” and said “he needed more assistance from

the U.S. for the special HNP units such as the SWAT team,”

Sanderson reported in a Jan. 25, 2007 cable.

Two of Andrésol’s advisors “are

funded by [the Embassy’s] NAS,” noted Tighe in a Jul. 15,

2009 dispatch approving of Andrésol reappointment as police

chief. “Post views the renewal of Andrésol's mandate as the

best possible result,” he concluded. “As DG he has worked

well with the USG on reform of the HNP and no other candidate

was viewed by Post as viable or trustworthy.”

“Andrésol has not only

promoted honesty and integrity within the HNP, but has

undertaken significant initiatives,” Sanderson wrote in

another typical Jun. 16, 2006 cable which reveals Washington’s

control of the HNP. “We look forward to maintaining our own

close bi-lateral cooperation through him and expanding overall

multi-lateral coordination as we intensify our efforts to

rebuild the HNP.”

But even President Préval and

his Prime Minister Jacques Edouard Alexis, who kept a friendly

front with the U.S. Embassy, were worried about how the U.S.

Embassy was working “through” Andrésol. “[P]ost also

learned that the PM [Alexis] privately warned Andrésol... of

‘being too close to the Americans,’” Tighe reported in a

Dec. 26, 2006 cable.

As Martelly has veered from the

control of the U.S. officials who facilitated his rise to power

last year, his relations with Andrésol have deteriorated.

Last year, Martelly asked

Andrésol to appoint one of his partisans, Godson Orélus, as the

HNP’s Inspector General, the force’s number two post, a former

high-ranking police official told Haïti Liberté. This

would have made Orélus “the next in line to act as the HNP’s

chief,” according to the source. Instead, Andrésol appointed

Orélus as head of the DCPJ, the number three post.

In February, according to

another police source, Martelly asked Andrésol to transfer the

heavy weapons of units like the Company for Intervention and

Maintenance of Order (CIMO) and SWAT team to the Palace Guard,

which is under the command of former “rebel” leaders Godwork

Noel and Jacky Nau. Andrésol refused.

“Relations between the HNP’s

Director General and President Martelly are worsening from day

to day,” reported Robenson Geffrard in the daily Le

Nouvelliste. “Mario Andrésol practically does not respond

to phone calls from the National Palace nor to those from the

Ministry of Justice and Security, according to a very

influential member of the government. ‘He doesn’t respond to

anybody.’”

In a slap to Andrésol,

President Martelly has made several visits to various police

units like the CIMO and SWAT team, without informing or

including the police chief, as is customary.

Last week, acting Justice

Minister Michel Brunache reportedly called on Andrésol to make

an “honorable exit” from his post, but Andrésol has vowed

to remain in his post until the end of his mandate on Aug. 18.

According to Geffrard’s

high-placed anonymous government source, Andrésol “thinks

that he has the support of the international community.”

Now Martelly is trying to turn

the tables on Andrésol. Under pressure from Washington, the

president is pretending that he wants the Pink Army’s training

camps closed and is asking Andrésol to do it.

“Paradoxically, the

government knows perfectly well that the police would not be

able to dislodge the ‘former soldiers,’” Geffrard reports. “There

is a disproportionate rapport of force. ‘The HNP cannot do it,’

acknowledged this influential government official.”

But another formerly

high-placed police source told Haïti Liberté that

Andrésol wouldn’t go after the proto-FAdH’s camps even if he

could. “Andrésol sees that Martelly is under pressure from

the so-called international community to shut down the camps and

that he is giving the problem to Andrésol, trying to make him

look ineffective,” the source said. “But Andrésol is

playing smart too, not taking the bait. In effect he’s telling

Martelly: you made this problem, you fix it.”

On Mar. 29, the 25th

anniversary of the ratification of Haiti’s 1987 Constitution,

Guy Philippe will leave his redoubt in the southern town of

Pestel to lead a march of former soldiers in the northern city

of Cap Haïtien demanding reestablishment of the FAdH. This is

the neo-Duvalierist sector flexing its muscle in Andrésol’s

face.

What will be Andrésol’s

reaction to his former comrades-in-arms who are now arrayed

against him? Just three years ago, Andrésol was hunting for Guy

Philippe, according to the U.S. Embassy. “Two separate

deployments of HNP SWAT officers took place to Pestel,

stronghold of wanted drug trafficker and disqualified Senate

candidate Guy Philippe,” wrote Ambassador Sanderson in a May

22, 2009 secret cable. “The initial deployment of 15 HNP on

April 7 was to ensure that the polling place, closed by Philippe

following his disqualification, would open on April 19 for the

Senate election as scheduled. In reality, it was also intended

to establish a stronger HNP presence in Pestel to facilitate

active efforts to arrest Philippe. 18 additional SWAT officers

were deployed on April 18. HNP DG Andrésol has vowed to keep

them there until Philippe is arrested.” Will Andrésol (or

the DEA or MINUSTAH) dare to try to arrest Philippe on Mar. 29?

Interestingly, some of the

Lavalas base groups which might have once been the targets of HNP crackdowns a few years ago are now defending Andrésol since

they see him as a temporary ally in the fight to stop the

establishment of Pink Army. They fear Martelly’s new force could

be as savage and deadly as the Tontons Macoutes. Lavalas base

leaders like Franco Camille and Ronald Fareau have gone on the

radio to champion Andrésol as an honest and well-meaning cop.

The stakes in this struggle are very high, and the

possibility of bloodshed cannot be ruled out. The HNP chief is

as aware of this as anyone. Andrésol was “frank about his

status in Haiti after his term ends,” wrote Sanderson in a

Feb. 22, 2007 secret cable, “saying that he would have to

live in exile to stay alive.” |