|

Last November,

the International Lawyers Bureau (BAI), based in Port-au-Prince,

and the Institute for Justice and Democracy (IJDH), based in

Boston, filed a complaint at the United Nations’ headquarters in

New York demanding reparations from the world body for starting

Haiti’s cholera epidemic, today the worst in the world (see

Haïti Liberté, Vol. 5, No. 17, 11/9/2011).

The

water-borne disease has sickened about 523,000 Haitians and

killed over 7,000. Those numbers will be spiking in the coming

weeks now that the rainy season has arrived.

The

suit requests UN financial compensation for 5,000 Haitians who

are cholera survivors or close family members of someone killed

by the disease. The petitioners also call on the UN to take

constructive action to prevent cholera’s spread and to formally

accept responsibility for importing cholera into Haiti.

Until

now, the UN has not officially replied to the complaint, saying

it is still “being studied,” and continues to deny

responsibility. Just last week, the UN Secretary General’s

spokesman said that “it was not possible to be conclusive

about how cholera was introduced into Haiti.”

But

Dr. Evan Lyon disagrees. “There is no doubt” that UN

Nepalese troops brought cholera into Haiti when they returned

there in October 2010 from Nepal, where the disease is endemic,

he said. “From a micro-biologic and genetic point of view,

epidemiologically,... the strains in Haiti and Nepal are

identical. It’s like matching, in criminal forensics, a

blood sample or some other piece of tissue; you can tell where

it comes from.”

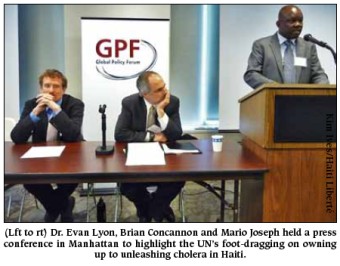

Dr.

Lyon, who fought, as part of Partners in Health, on the

front-lines against the disease when it exploded in Haiti’s

Artibonite River basin, was speaking to a room-full of UN

diplomats and journalists at 777 UN Plaza in Manhattan on Apr. 9

in a conference organized by the Global Policy Forum, an

independent policy watchdog that monitors the UN’s work.

Speaking with him at the event were the BAI’s lead lawyer Mario

Joseph and Brian Concannon, Jr., the head of the IJDH.

They

were also joined by Abby Goldberg of the New Media Advocacy

Project (NMAP), who presented a beautifully crafted six-minute

video entitled “Fight the Outbreak: Cholera in Haiti & the

United Nations”

http://vimeo.com/39599088 .

The

presentations were followed by a question and answer period

where the audience repeatedly asked who in the UN was refusing

to accept responsibility for the outbreak and why.

We

present here the abridged remarks of Dr. Lyon, who now teaches

medicine at the University of Chicago, and Mr. Joseph.

Dr. Evan

Lyon

Cholera is really a 19th century problem. It’s not a

modern medical problem. It’s a solvable problem. Medicine has a

very small role to play actually in the control of the cholera

epidemic. It’s more an infrastructure, water and sanitation

problem than a medical problem.

Cholera was understood to be a water-borne illness before germs

were understand to cause illness. Before germ theory, in 1854, a

man named John Snow made a map of a cluster of cholera outbreaks

along Broad Street in London. He found a pump where most of

these cases were clustered. He took the handle off the pump, and

that’s assumed to be one of the first effective public health

interventions around infectious disease.

Now

unfortunately we’re faced in Haiti with an epidemic which is

rampant, it’s not going anywhere, and it has now infected close

to 5% of the population. There are an estimated 500,000 cases in

a country of 9 million people. If that were the United States,

that would be 12.5 million people sick. That’s the city of New

York.

Everyone in Haiti has been touched by the disease. It’s very

fast and very frightening. And again it’s not going anywhere.

To

prevent the illness with proper water and sanitation is really

the only option. Medicine can save lives, but to stop the

epidemic, there needs to be better infrastructure and better

capacity to provide safe clean water to people, and, of course,

sanitation.

There

is no municipal sewage system in the entire nation. Only half of

people have access to any improved water source in rural places.

That’s probably 25% of all people. So most people are living,

predictably, without any access to clean water...

In

2007, along with a team from NYU here in the city, some

colleagues in Haiti, and other partners in Washington, DC, we

did a study [on water]... in Port-de-Paix, a city of about

100,000 people in the north of Haiti. We spent several months

studying the problem, including a household survey and water

sample testing.

Haiti’s water supply has always had an underlying vulnerability,

and the world community understands this. In Port-de-Paix, in

the summer of 2007, people were living on nine liters of water a

day. International standards say, for survival, one should have

access to 20 liters a day. For health, it’s better to have 50

liters a day. Long term, these are households which are living

on nine liters a day or half of what’s estimated for basic

survival in refugee settings and displacement settings.

Fourteen of the 19 samples we tested were contaminated with

infectious material. People were spending 12% of household

income for water. Accessibility both physically and financially

were very low. There were vulnerabilities for women and others

collecting water. It was a really dramatic situation which has

yet to be remedied.

A

cholera strain, that is frequent in Southeast Asia, had a

documented outbreak in Nepal some months before October 2010.

Peacekeeping troops carrying that germ came to Haiti. There was

a basic breakdown in sanitation, and the germ was introduced

into the water system.

There

is no doubt, from a micro-biologic and genetic point of view,

epidemiologically, that the strains in Haiti and Nepal are

identical. It’s like matching, in criminal forensics, a blood

sample or some other piece of tissue; you can tell where it

comes from. And the germ that is now epidemic in Haiti, that is

causing the largest outbreak in the world, is identical to the

strain that is from Nepal, and we also know that the soldiers

moved from Nepal to Haiti. So that is, without any doubt, the

proximate cause of this outbreak.

With

Haiti’s poor water and sanitation systems, it blew up very

quickly... None of my colleagues or myself , none of us had ever

treated cholera until this outbreak. Very quickly it spread down

the river valley. I work with a group in St. Marc. We went from

no documented cases on Oct. 18, [2010,] to 18 documented cases

of diarrheal disease the next day, to 400 cases on the Oct. 20.

Mortality was around 9% in that first wave of the epidemic. We

didn’t have the means or the knowledge to deal with it on a

medical or community level. There have been major improvements,

and now mortality is closer to 1%. But that still is drastic

considering the size of the epidemic.

If

someone reaches medical care in time, there’s very low

mortality. Interventions are quite simple: hydration with oral

fluids, salt water, and sugar. If that fails or isn’t possible,

intravenous hydration is needed, which is a little harder

logistically, but not rocket science. It’s very doable.

Antibiotics may play a role, but even that’s unclear.

There

is a vaccine available. There is currently not enough vaccine in

the world to treat this epidemic. Should the world decide to

invest in it at the level needed, there are some vaccine trials

that may start soon. They have been hampered by a variety of

logistical concerns.

The

world was really not ready for this epidemic. Certainly, Haiti

was not ready for it.

The

epidemic will be around for at least a decade. Best estimates

are that, even with improvements to water and sanitation, even

with an adequate response for treatment, and what’s available

for prevention, the epidemic will last for some time.

One

of the reasons for that is because there is no immunity. Haiti

has not seen cholera in many generations. Haiti was largely

spared from the global pandemics that were lead killers in the

19th century. But now, with this large, fast moving

epidemic, in a context where there is no immunity, people have

not been exposed to the germ, so noone is protected. The vaccine

would help jumpstart that process and allow people some limited

protection based on exposure.

If

there were investment in water and sanitation, it would change

generations of lives in Haiti. Although there aren’t great

statistics in Haiti, there are 15 to 20 thousand deaths from

diarrheal illness in Haiti each year, most of that among

children. It’s estimated that 16% of under 5 mortality is from

water-borne disease.

If we

could, as a world community, invest in water and sanitation, we

could change the primary dynamic of this epidemic. There would

be side-benefits for generations, literally. We would save,

potentially, tens of thousands of lives per year if there were

meaningful water improvements...

Medical people are not the answer to this problem. Public

health, sanitation and infrastructure are the answer.

Lawyer

Mario Joseph

We

filed a complaint with the UN on behalf of 5,000 victims of

cholera in November, 2011. The cholera victims ask the UN to

provide three things. First, the clean water and sanitation

infrastructure necessary to control the epidemic. Second,

compensation for the victims, many of whom lost everything they

had, or were forced from poverty into starvation by the loss of

the family wage earner. Third, the victims want an apology to

the people of Haiti for the reckless introduction of cholera

into our country.

We

filed the complaint with the MINUSTAH claims commission in Haiti

and the UN General Secretariat in New York. We received a

response acknowledging UN receipt of the complaint in December,

but have not heard anything else from the UN.

The

UN and Haiti signed an agreement called the Status of Forces

Agreement, or SOFA, that regulates the rights and

responsibilities of UN peacekeepers in Haiti. The Haiti SOFAs,

like SOFAs for all UN missions, has a provision giving the UN

protection against the jurisdiction of Haitian courts. But the

SOFA also requires the UN to set up an alternative mechanism,

called the Standing Claims Commission, to settle claims against

it. MINUSTAH has not set up a standing claims commission in

Haiti, or, to our knowledge, anywhere else in the world in over

60 years of peacekeeping.

There

is a developing legal doctrine that "immunity cannot mean

impunity." If an international organization with an immunity

agreement does not provide a fair mechanism for responding to

claims against it, courts will decline to enforce the immunity

provision. Right now we are asking the UN to provide our clients

with their day in court. If the UN does not do so, we will ask a

national court to do so. Currently we are researching avenues

for justice in Haitian, U.S. and European courts.

Haiti's cholera epidemic is a perfect illustration of the

dangers of impunity. Only an organization with no fear of

consequences would have acted so recklessly with a disease as

dangerous as cholera. As you have heard from Evan and seen on

the NMAP video, the introduction of cholera into my country was

not an accident, but the result of a series of decisions made

with no regard for the safety of people in Haiti. The UN made a

decision not to test peacekeepers coming from a cholera zone,

even though it had, itself, warned of Haiti's vulnerability to

cholera. The UN then made a decision not to safely dispose of

the wastes at the Mirebalais base. It is important to note that

the waste disposal problem in Mirebalais was not an isolated

incident, but part of a pattern of poor waste disposal at

MINUSTAH bases throughout Haiti.

The

UN's defense in this case, that "a confluence of factors"

caused the bacteria the UN introduced to turn into an epidemic,

would only be used as a defense for an institution with no fear

of being brought to court. The UN was fully aware of these

factors before it decided to not test its peacekeepers or safely

dispose of their wastes. As a result, that excuse would be

rejected in both the Continental law system and the English law

system. Under both, knowledge of a dangerous condition is a

reason for being more careful, not an excuse for being reckless.

The

UN's impunity problem in Haiti started before cholera. In its

seven years, the mission and its personnel have been involved in

many serious incidents of malfeasance, including widespread

sexual assault, individual murders and large-scale killings.

Each time MINUSTAH resists attempts to hold it accountable, and

so the cycle is repeated.

Right

now we are expecting that the UN will take responsibility and

provide the cholera victims a fair hearing. There are several

encouraging signs since we filed the lawsuit. In January several

UN agencies joined a "call to action" that conceded that

the only way to effectively control the epidemic was

comprehensive water and sanitation. Last month UN Special Envoy

to Haiti Bill Clinton conceded that UN troops were the "proximate

cause" of the cholera epidemic. That is a little like

someone saying that the sky is blue, except in the context of

repeated UN denial, it was an important step forward. Also last

month, the Representatives of Pakistan and France displayed the

leadership needed for a just response to the cholera epidemic,

by urging the UN to take responsibility for cholera.

This

progress has not led, as far as we know, to any concrete plans

for stopping the cholera's killing in Haiti, or a financing plan

for the necessary infrastructure. So it is necessary for more

organization to play a leadership role and stand up for the

people of Haiti.

When

the cholera outbreak started in Haiti, we did not think of

filing a lawsuit, because we assumed that with such clear

liability and such great harm, that the UN would respond in a

responsible manner. But when the UN experts report came out in

May 2011, we knew we had to act. The report conceded the facts

showing the UN responsible, but somehow came to a conclusion

that it had no responsibility for its action. We knew then that

the UN's impunity addiction would keep it from treating cholera

victims fairly, so we acted.

One place that the UN can start looking for money to

save lives in Haiti is the budget of MINUSTAH, currently at over

$800 million per year or $2.4 million every day. MINUSTAH has

had one in ten UN peacekeepers, for seven years, in a country

that has not had a recognized war in my lifetime, and does not

pose a threat to other countries. Shortening MINUSTAH's presence

by just one year would, by some estimates, pay for the entire

water and sanitation infrastructure Haiti needs to control

cholera. That would save over 70,000 lives over a decade. |