|

Throughout 2004 and 2005, Haiti’s unelected de

facto authorities, working alongside foreign officials,

integrated at least 400 ex-army paramilitaries into the

country’s police force, secret U.S. Embassy cables reveal.

For a year and a half

following the ouster of Haiti’s elected government on Feb. 29,

2004, UN, OAS, and U.S. officials, in conjunction with post-coup

Haitian authorities, vetted the country’s police force –

officer by officer – integrating former soldiers with the goal of

both strengthening the force and providing an alternative “career

path” for paramilitaries.

Hundreds of police

considered loyal to President Jean-Bertrand Aristide's deposed

government were purged. Some were jailed and a few killed,

according to numerous sources interviewed.

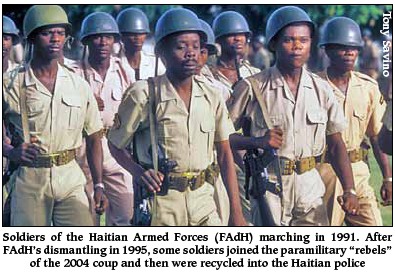

At the same time, former

soldiers from the disbanded Haitian Armed Forces (FAdH), who

were assembled in a paramilitary “rebel” force which

worked with the country’s elite opposition to bring down

Aristide, were stationed – officially and unofficially – in

many towns across the country.

As part of this deployment, an

extrajudicial strike brigade was assembled in Pétion-Ville. It

carried out brutal raids (sometimes alongside police), often

several times a week, in the capital’s coup-resisting

neighborhoods, as documented in a November 2004 University of

Miami human rights study.

The secret U.S. dispatches

detailing the police force’s overhaul were part of 1,918

Haiti-related cables obtained by the media organization

WikiLeaks and provided to Haïti Liberté.

The cables show that UN and

U.S. officials saw the program as a useful way to disarm and

demobilize combatants, but the implications of providing

coup-making paramilitaries with government security jobs have

been hidden or ignored.

The cables also make clear

that the US officials – using “redlines” and “red

flags” – took on a leading role in the “reforms,”

minutely following the process of repopulating Haiti’s police.

Millions of dollars in

funding for the demobilization and integration of the FAdH were gathered — mainly through the UN and the U.S. — but officials

also looked to other governments for funding.

Immediately after the coup,

the integration process was carried out by officials of the

so-called Interim Government of Haiti (IGOH), under U.S., OAS

and UN supervision. Then, starting in November 2004, a

longer-term apparatus, the UN’s DDR (Disarmament,

Demobilization, and Reintegration) program, was set up. Part of

its duties included a continued integration of some of the

paramilitaries into the Haitian National Police (HNP).

The U.S. Embassy cables go

into detail about the integration of paramilitaries into the HNP

and other government agencies. One of the most revealing cables

is entitled “Haiti’s Northern Ex-Military Turn Over Weapons;

Some to Enter National Police.”

The Mar. 15, 2005 cable

provides an overview of a gathering two days earlier in Cap-Haïtien

attended by Haiti’s de facto Prime Minister Gérard

Latortue and the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative

to Haiti, Juan Gabriel Valdès. The officials oversaw a “symbolic

disarmament,” where more than “300 members of Haiti's

demobilized military in Cap-Haïtien” turned in a token seven

weapons and then boarded buses to the capital.

The UN and IGOH officials

parked the paramilitaries at Port-au-Prince’s Magistrates’

School, where many other ex-soldiers were being placed.

The cable describes how

previously high-level IGOH officials had made promises to the

ex-FAdH paramilitaries. Some “of the ex-soldiers in Cap-Haïtien

said they had been told by the PM's nephew and security advisor

Youri Latortue and the PM's political advisor Paul Magloire that

they would be admitted into the HNP,” explained the cable by

U.S. Ambassador James Foley. “This raised a red-flag for us

and the rest of the international community...”

But at the Mar. 13 meeting,

Gérard Latortue “made clear this was not the case,”

telling the paramilitaries “that integration into the HNP

would be a possibility for some, but they had to understand that

not everyone would make it into the police. Ex-soldiers

not qualified for the HNP could be hired into other public

administration positions (e.g., customs, border patrol, etc.),”

Foley wrote.

But the UN and IGOH

authorities wanted to keep some of the ex-military together as a

cohesive unit prepped for integration into the police, the cable

reveals. The officials handed the matter over to UNOPS, a wing

of the UN that focuses on project management and procurement.

Accordingly, “UNOPS has

been working to relocate both the Managing Office [for

Demobilized Military] and the approximately 80 individuals from

the Magistrate's School to a former military camp in the

Carrefour neighborhood outside of Port-au-Prince,” wrote

Foley. (In March 2011, the author visited an ex-FAdH-run

training camp in the Carrefour area.)

UN and U.S. officials

appear to have often focused on achieving symbolic successes

like the “demobilization” of paramilitary forces. “The

symbolism of the ex-military disarming and leaving Haiti's

second-largest city represents a significant breakthrough,”

Foley concluded in his Mar. 15 cable.

At the time, around 800

ex-military men were being housed in Port-au-Prince, with UN

help.

Of the 400 former soldiers

integrated into the police, about 200 came in 2004 from the 15th

graduating class of HNP cadets (called a “promotion” in

Haiti), and 200 from the 17th promotion in 2005, the

cables say.

The number 200 was no

coincidence. The Embassy had told the IGOH that “the USG

[U.S. Government] would not support more than 200 former

military being included in Promotion 17” because “the USG

was concerned that inclusion of ex-FADH in large numbers would

detract from ongoing police reform measures; they therefore had

to be closely scrutinized,” a May 6, 2005 cable explains.

This cable also reveals

Washington’s dominance of the police force’s reconstruction. In

a meeting, the Embassy told the HNP’s chief Léon Charles that “the

practice of allowing a class of people to receive special quotas

for class enrollment (as had happened with the ex-FADH) had to

end,” wrote Foley. Dutifully, “Charles agreed and stated

that the practice would end immediately.”

This did not mean that

ex-soldiers wouldn’t continue to be integrated, only that “future

recruitment drives would make no distinction with regard to the

former military, but would also not discriminate against anyone

for previous duty in the Haitian Armed Forces,” Charles

said, according to the cable.

An Apr. 5, 2005 cable

explains that the 16th promotion of 370 HNP cadets

included “none of [those who] had a history of ex-FADH

activity.”

In another Mar. 15,

2005 cable entitled “DG [Director General] Charles Update on

Ex-FADH in the Haitian National Police,” Foley outlined how

the process of integration was occurring with new HNP cadet

classes.

“OAS officials

charged with vetting police candidates reported approximately

400 ex-FADH candidates at the Police Academy on March 11

undergoing physical fitness testing,” his cable explained.

The men, who had just previously served in paramilitary squads

around the country, were vying for 200 slots in the HNP. The

cable explains that a number of such individuals had been hired

in prior months.

Police chief Charles,

stated “that the ex-FADH from the 15th class who were rushed

on to the streets last fall [of 2004] would return to class.”

It was clear that officials felt somewhat worried about the new

men they were bringing into the police force, so they decided

that the ex-FAdH cadets from the 17th promotion

would, upon graduation, “be deployed throughout Haiti on an

individual basis and not as a group.”

Charles added that,

among the 200 ex-FAdH in the 15th promotion, most “had

been assigned to small stations in Port-au-Prince,” adding

that, “although they were disciplined, they were older and

physically slower.”

OAS officials noted

that Haitian police officials who were now assisting the OAS in

its vetting process feared some of the former soldiers they were

interviewing: “HNP personnel assisting the OAS with the

vetting program were afraid to interview some of the ex-FADH

candidates out of concern they might be targeted if the panel

disqualified an applicant.”

The U.S. embassy

closely supervised how Haitian de facto officials

conducted the integration, worried about the impact of any

failures. Foley was pleased that Charles was holding ex-soldiers

to “the same requirements as civilians for entrance into the

HNP,” a policy resulting from “continuous pressure from

us,” he wrote in the Mar. 15 cable. But Foley worried about

“political pressures and decisions of PM [Gérard] Latortue,

Justice Minister [Bernard] Gousse, and others,” his cable

reported.

“We have raised

this issue with them on countless occasions, pointing out the

real danger the IGOH runs of losing international support for

assistance to the HNP if the process of integrating ex-FADH into

the police does not hew to the redlines we have laid down,”

Foley wrote.

Embassy officials,

along with the OAS mission, would “monitor the recruitment,

testing, and training process, including a review of the written

exam, test scores, and fitness results.”

Ambassador Foley

added that “the pressure to bring ex-FADH into the HNP

remains high.” He was likely referring to the calls made by

some of Haiti’s most powerful right-wing politicians and

businessmen, many having established relationships with the

paramilitaries back when they were soldiers.

Furthermore,

Chief Léon Charles was “worried that others in the IGOH had

made unrealistic promises to the ex-FADH about jobs in the HNP

in order to convince them to demobilize,” the ambassador

wrote.

Charles “fretted

that the Cap-Haïtien group set an example that others may

follow, and indicated the IGOH could have over 1,000 former

soldiers looking for jobs soon, including the 235 from Cap-Haïtien;

300 from Ouanaminthe; 200 from the Central Plateau; 150 from Les

Cayes; 100 from Arcahaie, and 80 from St. Marc.”

The second Mar.

15 cable concludes “that the USG was willing to contribute $3

million to the DDR process but could not release the funds until

the IGOH concluded an agreement with the UN on an acceptable DDR

strategy and program.” The U.S. Embassy, playing a dominant

role, was also clearly seeking to operate in accord with a

transnational policy network — U.S. officials had helped to

oversee other such integration processes in El Salvador and

Iraq, and the DDR program has been deployed in a number of other

countries where UN forces operate, such as Burundi, the Central

African Republic, Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo,

Liberia, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Uganda, Afghanistan,

Nepal, and the Solomon Islands.

After Charles

provided information on the monitoring and processes through

which the ex-FAdH paramilitaries were integrated into the police

force, Ambassador Foley remarked in an Apr. 5, 2005 cable: “The

fleeting reply to requests for updates on human rights

investigations demonstrate the HNP's inability to perform

internal investigations.”

During their

first year in office, IGOH authorities appear to have received

far less oversight in their handling of ex-FADH integration into

the police. “Until now, the Interior Ministry and/or the

Managing Office [for Demobilized Soldiers] have been in charge

of identifying possible ex-FADH candidates for the HNP,”

Foley wrote in one of his Mar. 15 cables. Then he made clear

Washington’s oversight: “This needs to change, so that

ex-FADH candidates for the police come out of the

reintegration/counseling process that the UN (with U.S. support

through the International Organization for Migration) will

manage.”

While former

soldiers were being integrated into the HNP, hundreds of police

who had been loyal to Aristide’s government were fired, their

names and positions documented in a list put together by Guy

Edouard, a former officer with the Special Unit to Guard the

National Palace (USGPN). In a 2006 interview, Edouard explained

that some of these former police and Palace security officers

had been "hunted down" after the coup. Furthermore, with

US support, Youri Latortue, a former USGPN officer and Prime

Minister Latortue’s security and intelligence chief, had led

efforts to "get rid of the people he did not like,"

Edouard said.

Gun battles

continued to occur between the Haitian police and a handful of

gangs in the capital’s poorest slums well into 2005, and on

numerous occasions, police opened fire on peaceful anti-coup

demonstrations. “April 27 was the fourth occasion since

February where the HNP used deadly force,” explained a May

6, 2005 cable. The Embassy was vexed that “despite repeated

requests, we have yet to see any objective written reports from

the HNP that sufficiently articulate the grounds for using

deadly force. Equally disturbing are HNP first-hand reports from

the scene of these events. These are often confusing and

irrational and fail to meet minimum police reporting

requirements.”

The HNP,

however, was working with UN forces in conducting lethal raids.

Léon Charles acknowledged that UN troops had a “standard

practice” of putting more lightly armed HNP forces in front

of its units as they moved into Cité Soleil, and this “often

resulted in the HNP overreacting and prematurely resorting to

the use of deadly force,” the May 6 cable notes.

In a 2001 study

published in the academic journal Small Wars and Insurgencies,

researcher Eirin Mobekk explained how the U.S. worked to

integrate large numbers of former soldiers into the HNP as

Aristide, to thwart future coups, dissolved the FAdH in 1995.

Washington’s strategy was to hedge in Lavalas with the new

police force.

A decade later,

this policy was resurrected. Just as Washington recycled part of

the military force that carried out the 1991 coup, it recycled

part of the paramilitary force that carried out violence leading

up to the 2004 coup.

The WikiLeaked

cables reveal just how closely Washington and the UN oversaw the

formation of Haiti’s new police and signed off on the

integration of ex-FAdH paramilitaries who had for years prior

violently targeted Haiti’s popular classes and democratically

elected governments.

Jeb Sprague will publish a book on paramilitarism later this

year with Monthly Review Press. He has a blog at

jebsprague.blogspot.com and tweets as

Jebsprague. |