|

Haiti might be “poorest country in the

Americas,” but it is also sitting on a gold mine.

New Prime Minister Laurent

Lamothe says he’s banking on the wealth in Haiti’s northern

mountains to lift the country out of poverty, but if history is

any guide, the mining of gold, silver and copper hidden in the

hills will mostly benefit foreign shareholders as it scars and

pollutes an already denuded and fragile landscape.

While a handful of farmers earn

$5 a day building mining roads, and while journalists talk up

one or two drilling sites, quietly and carefully a Canadian

company, Eurasian Minerals, has been buying up licenses – 53, to

be exact – and cutting backroom deals, perhaps with the

assistance of a high-ranking former minister now on the payroll.

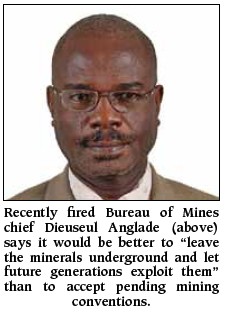

The deals are so good for the

mining companies, and so bad for Haiti, that the head of Haiti’s

state mining agency recently denounced them in an exclusive

interview with Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW), calling on his

government to either right the wrongs or “leave the minerals

underground and let future generations exploit them.”

“Mines are part of the public

property of the state; they are for the population,” said

geologist Dieuseul Anglade, who was then head of the Bureau of

Mines and Energy (BME). “They aren’t the property of the people

in power, or even the landowner.”

Eurasian and Newmont Mining,

its partner and the world’s Number 2 gold producer, are also

drilling illegally in one area – La Miel, in the northeast – in

collusion with certain government officials.

Haitian law differs from many

other countries. It is more bureaucratic, but it also insures a

modicum of protection up front. In order to drill – even for

exploration – companies must get a mining convention signed by

the prime minister and all the ministers. This convention sets

the terms for any eventual mine.

Eurasian and Newmont are

currently waiting for final approval of a new convention that

covers a huge amount of territory – about 1,350 square

kilometers of land. But the convention has not yet been signed,

partly because for most of the past 12 months, Haiti has been

without a prime minister.

“We are ready to drill,” Newmont’s Daven Mashburn said about the La Miel region in late

2011. “Because the government of Haiti doesn’t really care… we

can’t advance our licenses, and that means people can’t get

jobs.”

But the new government does

care. Not long after that interview, the licenses did advance,

although not in a legal manner.

“The government gave them a

kind of ‘waiver’ while they are waiting for the convention to be

signed,” explained Ronald Baudin, Haiti’s former Finance

Minister (2009-2011, prior to that he was Director General of

the ministry), who oversaw negotiations with Eurasian while

serving in the powerful position. “The government is conscious

of what damage they are doing to the company. They have camps

all over the country, with important logistics, and they are

blocked because the convention can’t be signed.”

Baudin, who left office when

the new government of President Michel Martelly took over in

2011, is now a paid consultant to the Eurasian-Newmont

partnership – called “Newmont Ventures.”

But a Memorandum of

Understanding (MOU) cannot trump the law. There’s no such thing

as a “waiver” to legislation.

“There is what is called a

‘hierarchy of law’ and according to the hierarchy, an MOU is

weaker than a law,” Haitian attorney Patrice Florvilus

explained. “An MOU cannot annul a law. It cannot allow something

which a law does not allow.”

The head of the state mining

agency – the BME – did not sign the MOU, nor did his office even

receive a copy, according to a source inside the BME.

“I didn’t agree with it for the

sole and simple reason that if the law says you can’t do

something, you can’t do it!” Anglade explained in an interview

on May 24, 2012.

One of the first official acts

of the new Lamothe government was to remove Anglade from his

post, perhaps in part because he refused to sign the MOU.

Anglade, 62, had worked at the BME for almost 30 years and had

been its director for most of the last 20. He has a reputation

for being honest.

Despite Anglade’s refusal, the

MOU was signed by the then-ministers of Finance and of Public

Works in late March, and Eurasian happily reported to its

shareholders on Apr. 23 that “[t]he joint venture is allowed to

drill on certain selected projects under the MOU, and drilling

is currently underway.”

Eurasian and Newmont know the

law and, according to a May 25 correspondence with HGW, appear

to believe Anglade signed the document. But he didn’t.

Anglade also disagrees with a

mega-mining convention that will likely be signed soon. After

three months of waiting, Haiti finally recently got a new prime

minister, Laurent Lamothe, who has pledged to make the country’s

laws more business-friendly.

According to Anglade, the final

version of the convention – which he rejected in a formal letter

to then-President René Préval and then-Finance Minister Baudin –

is much weaker than Haiti’s two, smaller existing mining

conventions (for 50 square kilometers each) because key

protective clauses have been removed.

Article 26.5 – in previous

conventions – set a cap on the expenses a company can claim at

60% of revenues. Now it is gone, according to the former BME

chief. “That means, the company can claim expenses up to 90% !”

Anglade said.

A second clause was also

removed, he said. Article 26.4 assured profits are split 50-50

between the mining company and the government.

“During two years of

negotiations, my position was clear,” said the 62-year-old, who

has been a public servant his entire life and who also teaches

math at Haiti’s State University. “The BME did not agree to

taking those two things out. That happened at the cabinet level,

at the Finance Ministry… They had meetings and they took them

out, but we didn’t agree. It was a minister who took them out:

Ronald Baudin.”

Asked about the convention, Baudin said he could not speak about the details. But, he

claimed, “today we have a text that has received the consensus

of the company, the BME, and the ministers of Public Works and

Finances.”

Not according to Anglade.

“There is nothing in the world that would make me take those

articles out,” he said.

Public Works Minister Jacques

Rousseau was Anglade’s superior. His ministry oversees the BME

and has the pending convention. Rousseau has refused five

requests for an interview; therefore the absence of the

protective articles in the document cannot be confirmed. Still,

Anglade swears that the measures are missing. Meanwhile, the

illegal MOU is public, and Baudin is openly on Newmont’s

payroll.

“I want the nation to be

clear,” Anglade explained when still in his post. “We here at

the BME are not responsible for all the things that give the

company an advantage.”

When Baudin was asked about the

potential conflict of interest of having served as Finance

Minister and then immediately afterward becoming a consultant to

Newmont, he did not flinch.

“I know that in other countries

when you finish in public service, there is a period of time

during which you do not have the right to work in the private

sector, but in that case, you get compensation,” Baudin said.

“We don’t have that legislation. I have not received one gourde

[about 2 US pennies] since I left, and I have to eat, right? I

have to clothe myself.”

What’s in Haiti’s hills?

Why would Newmont, Eurasian, and others

wait for years to get a convention signed and break Haitian law

with an MOU?

If geologists’ calculations are

correct, Haiti’s northern mountains contain hundreds of millions

of ounces of gold. With gold prices currently topping $1,600 an

ounce, one estimate puts the eventual take at $20 billion.

The Pueblo Viejo mine, just

across the Dominican border in the same “mineralization belt”

that runs across the island, has the largest gold reserve in the

Americas. It has already produced 5.5 million ounces of gold and

contains at least another 23.7 million. It’s also rich in

silver: 25.2 million ounces already mined and another 141.8

million to go.

With Haiti's apparently vast

reserves (and weak government), it is no wonder mining behemoth Newmont partnered with Eurasian, which is headed by a former

Newmont executive. Eurasian, via its local partner Marien

Mining, controls various kinds of licenses for one-tenth of

Haiti's territory, more than any other company.

A small Haitian-American mining

venture – VCS and its local partner Delta Mining – has or until

very recently, controlled, licenses for over 300 square

kilometers in the north; Canadian explorer Majescor and its

Haitian partners are sitting on licenses for another 450 square

kilometers. Taken together, foreign companies are sitting on

research or exploration permits for one-third of Haiti’s three

northern departments, 15% of the country’s territory.

Majescor is ahead of its

rivals, having recently moved to the “exploitation” phase for

one if its licenses. But VCS and Newmont/Eurasian are close on

its heels. All of the companies recognize Haiti’s potential.

“Haiti is the sleeping giant of

the Caribbean!” a Majescor partner said recently, while Eurasian

president David Cole boasted on a radio show: “We control over

1,100 square miles of real estate.”

An investor who calls himself a

“mercenary geologist” wrote: “It is obvious there is substantial

geopolitical risk in Haiti. But the geology is just so damn

good.”

The geology is good. One small

Eurasian site alone – the Grand Bois deposit – appears to

contain at least 339,000 ounces of gold (worth about US$5.4

billion at today’s prices) and 2.3 billion ounces of silver.

But the geology is not cheap.

Pit mines on the horizon

Because in most locations the copper,

silver, and gold deposits are spread out as tiny specks in the

dirt and rock – what is sometimes called “invisible gold” –

expensive and destructive pit mining will often be the only

option, but Eurasian’s partner Newmont knows its pits. The gold

giant opened the world’s first pit mine in Nevada in 1962 and

later dug in Ghana, New Zealand, Indonesia, and other countries.

In Peru, Newmont runs

the 251-square kilometer Yanacocha open pit mine, one of the

world’s largest. Not long ago, Newmont was accused of influence

peddling there when it was linked to former Peruvian spymaster

Vladimiro Montesinos. After allegedly assisting Newmont

negotiate favorable terms, a former U.S. State Department

employee ended up on the Newmont payroll. The company was also

accused of mercury and cyanide spills.

Undaunted, Newmont recently

embarked on an effort to open a second mega-mine nearby – called

the Minas Conga – but so far, farmers, environmentalists, and

local authorities have fought back with massive protests and in

the courts. Last month, a government-hired panel of European

experts, tasked with studying the plans, told Newmont it would

not be allowed to drain two high Andes lakes for the new mine.

As of May 29, Newmont had yet

not decided on its course of action, but an Apr. 27 Associated

Press story quoted Newmontʼs Richard OʼBrien as saying “if the

$4.8 billion project cannot be developed ‘in a safe, socially

and environmentally responsible manner’ while also earning

shareholders ‘an acceptable return’ Newmont will ‘reallocate

that capital to other development projects in our portfolio’.”

Newmont has had problems in

other countries too, more recently Ghana. The “Ahafo South” mine

is located in a farming region known as Ghana’s “breadbasket.”

So far, it has displaced about 9,500 people, 95% of whom were

subsistence farmers, according to the Environmental News

Service.

In addition to forcing farmers

from the land, Newmont poisoned local water supplies at least

once, by its own admission. In 2010, the company agreed to pay

US$5 million compensation to the government for a 2009 cyanide

spill that killed fish and polluted drinking water. Newmont

conceded proper procedures were not followed, and that its staff

also failed to properly notify Ghanaian government authorities.

While welcoming the possible

benefits well-built and -supervised mines might bring to Haiti, Anglade and other Haitian experts are worried that a pit mine,

which would use cyanide to recuperate gold from ore and dirt,

could be dangerous to Haiti’s already fragile environment.

In the neighboring Dominican

Republic, a government-controlled gold mine caused so much

contamination that the region’s rivers still run red as rain

releases metals from the ore left lying exposed.

“Mines can cause big problems

for the environment,” Haiti’s former Environment Minister

Yves-Andre Wainwright noted in a recent interview.

While serving in the

mid-nineties, Wainwright signed both of the existing mining

conventions. An agronomist by training, he noted that, in

addition to his heavy metal worries, some of the areas under

license are “humid mountains,” meaning they play “an important

biodiversity role and need to be protected, starting in the

prospecting phase.” The hills are also home to tens of thousands

of farming families. But no Environment Ministry personnel has

been seen at mine sites, according to Haitian community radio

journalists.

Finally, what concerns

Wainwright, as well as Anglade and other observers, is the

likely incapacity of Haiti’s “weak state” to control the mining

companies and the potential environmental damage.

“We have competent staff at the

Mining Bureau, but they don’t have the means to carry out their

jobs,” Wainwright said. “All the money that comes in from the

sand mines, and other mines, goes straight to the Finance

Ministry. Therefore, even though it is a sector that makes

money, the BME is impoverished.”

Wainwright’s assessment appears

correct. An audit of BME vehicles shared in January showed that

of 17 vehicles, only five were in working condition. Twelve were

out of service. With a budget of about $1 million, the BME is

also strapped for human resources. Only one-quarter of the 100

employees have university degrees. Another 13% are

“technicians.” The rest are secretarial and “support” staff.

“The government doesn’t give us

the means we need to be able to supervise the companies,” Anglade confirmed in an interview while still head of the BME.

“Most of our budget goes to salaries. We don’t really have an

operating budget.”

The World Bank’s private sector

investment arm – the International Finance Corporation – has

invested $5 million in Eurasian’s Haiti explorations. The bank

says Eurasian and Newmont have good track records, but it also

knows about mining’s potential negative impacts. Bank

representatives said they recognize the challenges facing

Haiti’s government and other “weak states.”

“Often the host country

government doesn’t have a lot of capacity, especially on the

environmental and social aspects,” Tom Butler, IFC’s global head

for mining, explained. “[But] one thing we don’t do is get into

telling the government what to do with the money it receives.”

Haiti coming in last in the “royalties

race”

How much money will come in, and when?

Recent articles have cited all kinds of promising figures, but

they leave out the fine print regarding the existing

conventions, and do not even mention the pending convention.

Also, no matter how good

the convention, aside from the up-front fees, any eventual mine

would likely not start paying revenues – taxes and royalties –

until five or even ten years down the road, because that’s how

long it takes to build a pit mine, and because companies are

allowed to depreciate their equipment first, delaying the move

from being “in the red” to “in the black.”

Newmont’s Daven Mashburn

confirmed that “it could easily be a decade. It usually takes a

decade to get these things going.”

“It’s likely that a big mining

company may declare losses year on year, even for ten years, if

cost deductions are too generous and there is little control,”

mining tax and royalties expert Claire Kumar confirmed in a

recent interview with HGW. “We see this happen all the time.”

A Christian Aid researcher who

authored the 38-page report Undermining the Poor – Mineral

Taxation Reforms in Latin America in 2009, Kumar said

Haiti’s two small existing (and about to be supplanted)

conventions sound good, since they promise a 50-50 split of

profits and put a cap on expenses.

What’s not so good, Kumar

noted, is Haiti’s royalty rate – 2.5%. According to Kumar and to

a recent news reports, the rate is one of the hemisphere’s

lowest.

“A 2.5% royalty share is really

low,” Kumar confirmed. “Anything under 5% is just really

ludicrous for a country like Haiti. You shouldn’t even consider

it. For a country with a weak state, the royalty is the safest

place to get your money. There is room for manipulation by the

company, but it’s not as big as you would think.”

Haiti’s royalty rate has yet to

catch up with what mining investors lament as a “royalties race”

and “resource nationalism.” In its annual Business Risks

Facing Mining and Metals report released last August,

accounting and investing firm Ernst & Young put “resource

nationalism” at the “top of the business risk list.” The agency

said that in late 2010 and in 2011, it counted 25 countries that

had or were threatening to hike royalty rates.

Many of those raising gold

rates recently are in Latin America. Ecuador now charges between

5 and 8%, Peru can get up to 12%, and Brazil is threatening to

raise its rate also. Last August, Venezuela went a step further

and nationalized its gold mining industry.

Writing about “resource

nationalism” in March, Reuters concluded “[it] has left mining

companies few options other than to venture into ever more

politically risky territory, including restive parts of

Africa”... or Haiti.

But with a royalty rate of

2.5%, a 10,000-soldier strong UN blue helmet force stationed

throughout the country, and indications that new mining

conventions will be more advantageous to foreign companies, the

risks there are likely lower than in recent decades.

Indeed, Majescor CEO Dan Hachey

applauded the 2011 election of President Martelly, saying,

“Martelly has stated that [Haiti] is open for business. We’ve

seen a lot of change since he’s been elected.”

The revolving door that landed

ex-Finance Minister Ronald Baudin on the Newmont team might be

one reason for the change. While still in power, he agreed to

deals like a cost-free, 50-year lease of land to a French

company in the north.

“We didn’t rent it – we made it

available to them,” Baudin said. “Because, when there is

something that is good for the economy, the government has the

obligation to encourage it.”

Haiti’s new prime minister –

Laurent Lamothe – is also very pro-business. A

telecommunications and real estate entrepreneur with companies

in Africa and Latin America, he has pledged to push through

business-friendly legislation in all sectors, including mining.

“Information on our national

reserves indicate that our land is rich in minerals and that now

is the right time to exploit them,” Lamothe said in his policy

speech before the Senate on May 8.

Lamothe also promised to change

mining law. In a recent interview with the Associated Press,

Lamothe pledged the new law would assure “the right portion

comes to the state” and that it also protects the environment

and local communities. But, he hedged, the new legislation would

do so "[a]s much as possible without hampering also the revenue

of the party, allowing them to do business."

Even before Lamothe took

office, Anglade told HGW he is aware of the move to change the

existing law. “I should tell you that the companies are doing

all kinds of lobbying to get the law changed so that it gives

them more advantages,” he said. “But they have too many

advantages already!”

Can a government whose motto is

“Haiti is open for business” and which is staking its bets on

assembly factories and a $5-a-day minimum wage (the lowest in

the hemisphere) be trusted to protect the country’s interests?

Mining giants have consistently

managed to negotiate highly profitable contracts even when going

up against much stronger states. What guarantee do Haitians have

that pro-business Lamothe will negotiate a better deal than

governments in Peru, Ghana, or other poor countries?

The potential for mining

revenue and even some low-paying jobs sounds good to many in

Haiti, where most people have to survive on less than $2 a day

and where un- and under-employment tops 66%. But is mining the

answer to Haiti’s woes?

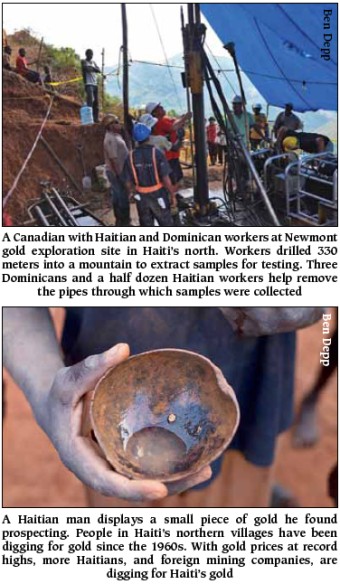

For Laurent Bonsant, a Canadian

mining contractor working for Newmont Ventures in the north, the

answer is “yes.”

“The one thing this country

needs is something to export,” he said as he supervised a site

where a team was drilling 24 hours a day for core samples 330

meters down. “They got nothing. If mining can do any good, it

will do good here.”

But Haiti has several exports,

and more importantly, in the past, mining has not done much

“good.”

In recent decades, foreign

companies mined bauxite and copper. Tens of thousands of

families lost their land, thousands of hectares were deforested,

and in some cases, land was poisoned. [See sidebar: Haiti’s

Grim History of Being “Open for Business”.]

Professor Alex Dupuy, Chair of

African American Studies and John E. Andrus Professor of

Sociology at Wesleyan University, is highly skeptical that the

new ventures will produce results much different than their

predecessors. Even though Haiti is no longer controlled by a

dictatorship as ruthless and corrupt as that of the Duvaliers,

there is little transparency, and no apparent means of auditing

or controlling local and foreign investors.

“I think the same thing is

going to happen,” said Dupuy, author of Haiti in the World

Economy – Class, Race and Underdevelopment, in a telephone

interview with HGW. “The mining industry doesn’t employ a lot of

people, and the local ones it will employ will be unskilled

labor. The cadres will come from overseas because usually these

companies come with their own technology.”

“As in the past, they will

expropriate peasants’ land. So, it will be the same thing, all

over again. The contracts being signed will be what the foreign

company wants, not necessarily what is in the best interests of

the country, even if they present it to the public as something

that is good for the country.”

Guatemala – a country socially,

economically and politically similar to Haiti – thought mining

could “do good” there, too, and let Goldcorp open the Marlin

Mine. But in 2010, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

called on the government to shut it down temporarily due to

health, environment, and human rights risks. A 2011 report by

mining experts associated with Tufts University recommended that

Guatemala significantly change the rules of the game: demand

higher royalties and other revenues, assure better environmental

protection and cleanup, and guarantee some monies reached host

communities.

“Without good governance and

productive investment, the local legacy of the Marlin mine could

well be ecological devastation and impoverishment,” the authors

wrote.

Anglade is worried something

similar could happen in Haiti, where government control is

virtually nil. For example, although it is illegal to cut down

trees, freshly sawn wood is stacked for sale in marketplaces all

over the country. Today Haiti’s tree cover is just 1.5%.

Up north, many of the farmers

who might have benefitted by leasing their land to mining

companies sold out long ago to savvy land sharks and businessmen

associated with previous mining ventures in Grand Bois, a

Eurasian site. Over a dozen families now farm land they no

longer own.

Anglade remembers well. “When I

heard that was happening, I went up there myself, to tell people

not to sell, because there was gold in the land,” he said. “But

they sold.”

Today, the poor families who

still farm those lands as tenants, and hundreds of their

neighbors, are worried about pollution and about being kicked

off their plots. Last year, over 200 families were ousted from a

nearby fertile plain to make way for a new free trade zone which

the Martelly government inaugurated.

In one region, Newmont has done

some “social works,” according to Anglade. The company built a

small bridge, a road for its all-terrain vehicles, and paid some

school tuitions. Farmers are still nervous.

“They say the company will need

to use the river water for 20 years, and that all the water will

be polluted,” worried farmer and peasant organizer Elsie Florestan, who lives near the Grand Bois site. “They say we

won’t be able to stay here.”

“The small group of people

who’ve gotten jobs are in favor of mining, but that’s 50

people!” added the 41-year-old, a member of Haiti’s Tèt Kole

Ti Peyizan (“Small Peasants Working Together”) peasant

movement. “If we don’t organize and make some noise, we’ll be

completely pushed aside,” she warned.

Florestan and other farmers

have been watching mining crews take tens of thousands of

samples from every hill and dale for years, all across the

north.

“They don’t even ask you who

owns what land,” noted peasant organizer Arnolt Jean, who lives

in Lakwèv, near the Dominican border. “They come, they take big

chunks and put them in their knapsacks, and they leave. All of

us are just watching. We need a government that controls what is

going on, because we don’t have the capacity to do that.”

In his community, people have

been panning for gold and digging their own tunnels for

generations. A day’s or week’s work might result in nothing, but

it might also bring up to $50 worth of gold, although Dominican

buyers usually pay only about half market price. Still, with

most families too poor to even send all their children to

school, many take to the hillsides with picks and shovels and to

the rivers with pans once they have planted their crops. The

landscape is pitted with holes. The rivers run brown with mud.

“Our country is poor, but what

is underground could make us not poor any more,” Arnolt said.

“But since our wealth remains underground, it’s the rich who

come with their fancy equipment to dig it out. The people who

live on top the land stay poor, while the rich get even richer.”

Produced in partnership with Haïti

Liberté.

This investigation was made possible in

part by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Haiti Grassroots Watch –

http://www.haitigrassrootswatch.org

– is a partnership of AlterPresse, the Society of the Animation

of Social Communication (SAKS), the Network of Women Community

Radio Broadcasters (REFRAKA), community radio stations from the

Association of Haitian Community Media and students from the

Journalism Laboratory at the State University of Haiti. |