|

by Bill Quigley and Amber Ramanauskas

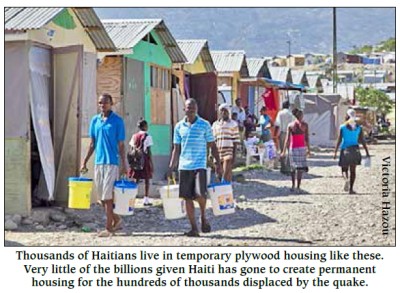

Despite billions in aid which were

supposed to go to the Haitian people, hundreds of thousands are

still homeless, living in shanty tent camps as the effects from

the Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake remain.

According to Oxfam

International, the earthquake killed 250,000 people and injured

another 300,000. Some 360,000 Haitians are still displaced and

living hand to mouth in 496 tent camps across the country

according to the International Organization of Migration. Most

eat only one meal a day.

Cholera followed the

earthquake. Now widely blamed on poor sanitation by UN troops,

it has claimed 7,750 lives and sickened over a half a million.

The Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti and their

Haitian partner Bureau des Avocats Internationaux have

filed legal claims against the UN on behalf of thousands of

cholera victims. Recently the Haitian government likewise

demanded over $2 billion from the international community to

address the scourge of cholera.

Haiti was already the poorest

country in the Western Hemisphere with 55% of its population

living below the poverty line of $1.25 a day. About 60% of the

population is engaged in agriculture, the primary source of

income in rural areas. Haiti imports more than 55% of its food.

The average Haitian eats only 73% of the daily minimum

recommended by the World Health Organization. Even before the

earthquake, 40% of households (3.8 million people) were

undernourished, and three out of 10 children suffered from

chronic malnutrition.

In November 2012, Hurricane

Sandy leveled yet another severe blow to the hemisphere’s

poorest country. Wind and 20 inches of rain from Hurricane Sandy

killed over 50 people, damaged dozens of cholera centers, and

badly hurt already struggling farming communities.

Despite an outpouring of global

compassion, some estimate as high as $3 billion in individual

donations and another $6 billion in governmental assistance, too

little has changed. Part of the problem is that the

international community and non-government organizations (Haiti

has sometimes been called the Republic of NGOs) have bypassed

Haitian non-governmental agencies and the Haitian government

itself. The Center for Global Development’s analysis of where

the money went concluded that overall less than 10% went to the

Haitian government and less than 1% went to Haitian

organizations and businesses. A full one-third of the

humanitarian funding for Haiti was actually returned to donor

countries to reimburse them for their own civil and military

work in the country, and the majority of the rest went to

international NGOs and private contractors.

With hundreds of thousands of

people still displaced, the international community has built

less than 5000 new homes. Despite the fact that crime and murder

are low in Haiti (Haiti had a murder rate of 6.9 of every

hundred thousand, while New Orleans has a rate of 58), huge

amounts of money are spent on a UN force which many Haitians do

not want. The annual budget of the United Nations “peacekeeping”

mission (MINUSTAH) for 2012-2013 is $644 million and would pay

for the construction of more than 58,000 homes at $11,000 per

home.

There are many stories of

projects hatched by big names in the international community

into which millions of donated dollars were poured only to be

abandoned because the result was of no use to the Haitian

people. For example, internationals created a model housing

community in Zoranje. A $2 million project built 60 houses which

now sit abandoned according to Haiti Grassroots Watch.

Deborah Sontag in the New

York Times tells the stories of many other bungles in a

critical article which reported only a very small percentage of

the funds have been focused on creating permanent housing for

the hundreds of thousands displaced. Many expect 200,000 will be

still in displacement camps a year from now.

The majority of the hundreds of

thousands of people still displaced by the earthquake have no

other housing options. Those who were renters cannot find places

to stay because there is a dramatic shortage of rental housing.

Many of those who owned homes before the earthquake have been

forced to move back into them despite the fact that these homes

are unsafe. A survey by USAID found that housing options are so

few that people have moved back into over 50,000 “red” buildings

which engineers said should be demolished.

One program, 16/6 (moving six

big camps back into 16 neighborhoods), promises to pay a

one-time $500 maximum rental subsidy for a family to relocate

from tent camps but this program will only benefit a tiny

percentage of the displaced population because it is currently

available only for about 5% of the people displaced. It is

limited to those living in the six most visible public camps in

Port au Prince. With the housing shortage in Port-au-Prince,

there are few places available to rent even with a subsidy.

Most of the people living under

tents are on private property and are subjected to official and

private violence in forced evictions, according to Oxfam. Over

60,000 have been forcibly evicted from over 150 tent camps with

little legal protection. Oxfam reports that many fear leaving

their camps to seek work or food because they worry that their

tents and belongings will be destroyed in their absence.

Dozens of Haitian human rights

organizations and international allies are organizing against

forced evictions in a campaign called Under Tents Haiti.

The fact that these problems

remain despite billions in aid is mostly the result of the

failure of the international community to connect with Haitian

civil society and to work with the Haitian government. Certainly

the Haitian government has demonstrated problems, but how can a

nation be expected to grow unless it leads its own

reconstruction? Likewise, Haitian civil society, its churches,

its human rights, and community organizations can be real

partners in rebuilding the country. But the international

community has to take the time to work in a respectful

relationship with Haiti. Otherwise, the disasters, like the

earthquake and hurricanes, will keep hammering our sisters and

brothers in Haiti, the people in our hemisphere who have already

been victimized far too frequently.

Bill Quigley is a human rights lawyer and teaches at Loyola

University New Orleans. Amber Ramanauskas is a lawyer and human

rights researcher. Thanks to Sophia Mire and Vladimir Laguerre

for their help. A copy of this article with full sources is

available. Bill can be reached at

quigley77@gmail.com, Amber

at

gintarerama@gmail.com

|