|

by Haiti Grassroots Watch

For more than two years, teams of U.S.

and Haitian businesspeople have been working on massive

public-private business deal: a factory that would transform

garbage from the capital into electricity, a resource so rare in

Haiti, only 30% of the population has access.

But the Phoenix Project

involves a technology potentially so dangerous that it has been

outlawed in some cities and countries. It would also commit

Haiti to a 30-year contract.

The project emerged following

the Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake. U.S. businesspeople said they came

up with the idea because they wanted to take part in the

reconstruction but “do more than make a profit.”

“We want Haiti to be energy

independent,” explained a Haitian representative of the U.S.

firm, International Electric Power (IEP) of Pittsburgh, PA. The

representative, a well-known businessman, agreed to speak with

Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW) only if his name was withheld,

saying he had critical words for some actors who he says are

trying to block the project. “We invested millions of dollars,”

he said. “It will be a shame if we have to abandon it.”

Ashes to Ashes

Phoenix and its 30 megawatt (MW) plant is

the brainchild of IEP and a “Waste to Energy” or WtE project. At

first, IEP was planning a 50 MW installation, which would also

use locally excavated “lignite” or “soft coal.” In many

countries where garbage is too “organic” or has too much liquid

content, coal or another fuel has to be added in order to raise

the caloric level of the burn. However, because coal-burning is

going out of vogue due to its contribution to global warming,

the lignite option was dropped, and IEP scaled back to a 30 MW

plant.*

Presented as a project that

will create “2,000 direct jobs and 8,000 indirect jobs in Haiti”

and that will “bring efficient solutions to various key problems

facing Haitian society today,” Phoenix is not a non-profit

enterprise. It is a business, a public-private partnership,

where the state will own 10% and the private entities will own

90%. In addition, the state – through the publicly-owned

Electricity of Haiti (EDH) – will promise for 30 years to pay

for the upkeep and operation of the factory and to buy

electricity “on demand,” according to IEP. Finally, the

government will donate 400 hectares north of the capital for the

factory site.

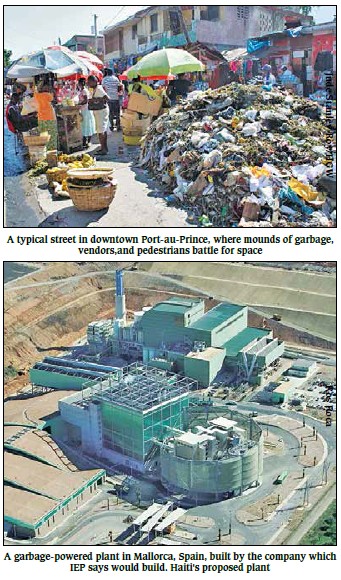

Founded in 2005, IEP has never

built an incineration plant. However, according to its website,

it is involved in one bio-digestion project and two wind

projects, one of them in Haiti. IEP says it will sub-contract

the factory construction to the Spanish firm Ros Roca, which

built a similar plant on Mallorca in that country.

IEP needs at least US$250

million to build the plant, according to Edward Rawson, vice

president of the company. In an email interview with HGW in

December 2012, Rawson said IEP is on the point of getting that

financing from the U.S. government’s Overseas Private Investment

Corporation (OPIC), which guarantees low-interest loans to U.S.

companies working in foreign countries. According to Rawson,

OPIC has “expressed interest in investing as a senior lender.”

However, he added, the agency is waiting for the results of an

IEP-sponsored study on the environmental impacts of Phoenix,

being carried out by the British firm Atkins.

The Pennsylvania business added

that the UN Environment Program (UNEP) is also doing a study,

this one for the Haitian government.

Asked for details, the UNEP’s

Andrew Morton responded, on Jan. 9, 2013: “Yes, UNEP is

conducting an independent review on behalf of the Government of

Haiti and in cooperation with International Electric Power. The

review is ongoing and the process is confidential.” Morton added

that the study could take another three to six months, but that

once completed, “a public report” will be published.

Haitian officials support Project

Phoenix

Project Phoenix falls right into the

government’s vision for energy, according to the Minister

Delegate for Energy Security, René Jean Jumeau.

“The project is part of our

Action Plan for the Development of Electricity,” he told HGW in

an interview on Oct. 10, 2012. “We aim to build factories that

will turn trash into energy all over the country. The

transformation of garbage into electricity will allow us to

achieve two objectives. The first is increase our energy output

and the second, linked to the first, is to better handle our

waste situation.”

The director of the capitol

region’s trash agency agreed. “Once this project is going, we

will have a much cleaner metropolitan region,” said Donald

Paraison, head of the Metropolitan Service for the Collection of

Solid Waste.

With the two major agencies on

board, IEP and the Haitian government signed two agreements in

May 2012, and they have already prepared the legal documents for

the eventual public-private business, known as a “Société mixte

anonyme” or “Anonymous Mixed Company,” in Haitian law. But the

project is blocked.

Rejections and Objections

IEP officials note that it appears the

Haitian government can’t move forward on the project, even

though it will be almost entirely privately financed.

“We are waiting on approval

from the multinational donor community,” Rawson said, because of

the project’s “size and complexity.”

IEP’s representative in Haiti

was more direct. “Certain ‘friends of Haiti’ are against the

project,” he sniped. “And the Haitian government is like a

child. It is afraid of moving forward because there were certain

objections to the project. Until those issues are addressed, it

won’t move ahead, because it is afraid it might lose its foreign

aid... But we are not giving up.”

In fact, the project was

rejected twice by the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC),

formerly responsible for approving and coordinating all

reconstruction projects. It never approved Project Phoenix.

Shut down since October 2011,

there was nobody from the IHRC available to discuss the dossier.

However, a staffer at one of the International Financial

Institutions (IFIs) who was a consultant to the commission at

the time (in other words, a staffer from the World Bank [WB] or

the Inter-American Development Bank [IDB]) agreed to speak with

HGW on the condition that his or her name not be revealed, since

staffers are not allowed to speak with journalists without

express permission.

A second IFI employee who was

also aware of the dossier told HGW: “both the WB and the IDB

studied the project and both of them rejected it because it

would be terrible for Haiti.”

More recently, the IDB’s Gilles

Damais told HGW that since the Bank is not part of the project,

it “will issue neither an approval nor a disapproval.”

However, in his emails to HGW,

IEP’s Rawson repeatedly gave the impression that the IDB, the

WB, and other institutions will be involved, saying they have

been “engaged.”

Risks and doubts

In the telephone interview, the first IFI

staffer outlined the principle objections to the project: a lack

of transparency and the potential commitment of the state in an

activity where it is already losing millions of dollars.

In fact, the Phoenix Project

was presented without any open bidding process. IEP chose its

partners without any government supervision. For example, the

Spanish company Ros Roca will build the factory, Boucard Pest

Control will be one of the firms collecting garbage, and the

Atkins company is carrying out the environmental impact study.

“We haven’t been able to move

forward yet because there are international partners who want to

make sure the project is carried out in a manner that is

transparent, competitive and unbiased,” Minister Delegate for

Energy Security, René Jean Jumeau, confirmed.

More worrying for critics is

the financial commitment EDH and the government would make for

the next 30 years. Phoenix is a “Build, Operate, Transfer” or

“BOT” project, where the investors get paid to run the factory

during a period of time. They will “make money on their

investment and then leave,” the IFI employee told HGW.

“The project is a big liability

for the government,” he added, noting that the Haitian

government doesn’t have the capacity to manage the existing

electricity system. Indeed, a recent IDB report claims that

“[t]otal electricity losses are close to 70% of electricity

production with commercial losses representing estimated revenue

loss of US$161 million/year for EDH.”

IEP recognizes the challenge.

“After 1986, there was a popular movement that became populism

and then turned into demagogic governments. All of that cost the

country dearly,” the IEP’s local representative said, adding

that the “bad governments” allowed the population to make

illegal connections to the grid in order to maintain their

popularity.

By signing an accord with the

IEP, the state and EDH will promise to pay a private (and mostly

foreign) company for 30 years. Port-au-Prince has already

experienced what happens when the state misses a payment. The

lights go out.

Environmental questions

The Phoenix Project also has two main

challenges at the environmental level.

The first concerns Haiti’s

trash. According to many studies and sources, Haiti’s garbage is

too “organic” and moist, EDH’s Ronald Romain recognized. "Our

garbage doesn’t have the necessary calorie level” for an

incineration-power plant, he said.

To assuage doubts, IEP did a

two-month study that it claims proved “we have the calorie level

we need,” the local representative said. But, like the

environmental impact study being done by Atkins, it was paid for

and supervised by IEP. Thus, its results are not reliable. HGW

did not receive a copy of the report.

But another 2010 study – “Haiti

Waste-to-Energy Opportunity Analysis,” done by a private firm

for a U.S. government agency – raises many questions about IEP’s

claims. Looking at three technologies for turning garbage into

energy – combustion or incineration, gasification and

biodigestion – the report took a clear position.

“The waste stream in Haiti is

estimated to contain between 65% and 75% organics,” the report

notes. “Food waste typically does not make a good fuel or

feedstock for combustion or gasification systems. This is

because the waste has high moisture content.”

The last challenge for

Phoenix’s proponents concerns the health and environmental

risks. Because they are so great, there is a global

anti-incineration movement that has even reached cities like

Washington, DC. The reasons? Incinerators can emit a cocktail of

hundreds of poisonous chemicals and heavy metals like mercury,

arsenic and lead.

According to GAIA, the Global

Alliance for Incineration Alternatives, “in some countries, like

Mexico, Brazil, Chile, and Argentina, there are state or

provincial laws, or municipal ordinances, which prohibit the

burning of trash.”

Nevertheless, the local

representative of IEP said the Phoenix installation would not

have any negative effect on the environment or on health. “After

the trash is burned, the emissions will be treated using a

sophisticated filtering system,” he said. “This will allow us to

remove the dangerous and sometimes valuable heavy metals. Our

emissions will be less toxic than those coming from the existing

electricity plants… and less toxic than the smoke that comes

from the open-air burning of trash, also.”

But anti-incineration groups

like GAIA say “even the most technologically advanced

incinerators release thousands of pollutants that contaminate

our air, soil, and water,” citing numerous studies to prove

their point.

Will the bird emerge from the ashes

again?

The future of the Phoenix Project is not

certain.

EDH operates at a loss, and two

studies remain unfinished. OPIC has not yet given the green

light. In addition, many wonder if a government that cannot

prevent the illegal felling of trees and use of Styrofoam dishes

(banned since last year) can adequately supervise an

incineration plan.

IEP claims it has the interest

and even the support of many actors inside and outside of Haiti.

But HGW discovered many reserves. And many risks.

The IFI employee thinks that

all the criticism means that perhaps “the project will die on

its own.” Perhaps.

Or perhaps, if Haitian and

international authorities continue to meet behind closed doors,

to carry out projects without transparency, and to insist on

speaking anonymously, this Phoenix, like its namesake, will be

reborn from its ashes.

* Note: IEP notes that lignite is not

definitely off the table, according to executive Edward Rawson

in an email addressed to HGW on Dec. 10, 2012: “[T]he creation

of a [lignite] mine and exploitation in partnership with the

Government of Haiti remains part of the current agreement

between IEP and GOH. This may eventually lead to the development

of a power plant near Maïssade.” The local IEP representative

added: “The foreigners refuse to let us use lignite because it

pollutes too much. However, in their countries, they use coal…

In fact, coal is what made Pittsburgh rich, for example!”

Haiti

Grassroots Watch is a partnership of AlterPresse, the Society of

the Animation of Social Communication (SAKS), the Network of

Women Community Radio Broadcasters (REFRAKA), community radio

stations from the Association of Haitian Community Media and

students from the Journalism Laboratory at the State University

of Haiti. |