|

by the Haiti Support Group

On May 26, 2011, just 12 days after

his investiture as President, Michel Martelly made his first

major policy pronouncement: the launch of the National Fund for

Education (FNE). Its aim was simple: get 1.5 million of the

Haitian children not regularly in school into the classroom by

the end of his five-year mandate. As a basic UN Millennium

Development Goal, the ambition was widely applauded by Haitians

and foreign donors alike.

The $360 million in funding needed for this ambitious project

was to come from levies on incoming telephone calls [$.05 per

minute-HL] and money transfers [$1.50 per transfer-HL], thus

tapping into the relative wealth of the several-million strong

Haitian Diaspora. As an added bonus, no new taxes would have to

be raised or old taxes actually collected at home in a country

where non-payment of tax by those rich enough to owe, is not

just the norm but is viewed as a basic right.

The fanfare that greeted the

Fund’s launch subsumed many of the vital questions being asked

at the time about the legitimacy of the electoral process that

had brought Martelly to power, his past as supporter of brutal

military rule and very serious doubts about his nationality and

thus whether he was actually eligible to be President.

Also ignored were voices

pointing out that unilaterally instituting such a tax without

Parliament’s consent was unconstitutional, or that the tax would

disproportionally affect the poorest, with the $1.50 levy on a

remittance of $20 dollars to a family struggling to feed itself

being the same as that on a transfer of hundreds of thousands of

dollars for a business or property purchase.

Equally unclear was who would

be the main beneficiaries: would the Fund be paying the private

school fees of better-off Haitians, thus using the remittances

of the poorest to subsidize the education of the relatively

well-off? And in a country where up to three-quarters of primary

school pupils are in private schools, would the Fund simply be

subsidizing the expansion of private schools rather than

reinforcing the woefully inadequate and underfunded state

sector?

Although the Central Bank – BUH

– was to be in charge of collecting the money on transfers, no

one knew who would be contracted to manage the levies on

international calls, or, indeed under what terms. Despite this,

the new President was adamant that the Fund would be managed in

an independent and transparent manner, citing the IMF and

auditors Price Waterhouse Cooper as guarantors.

As it turned out, Martelly

appeared to have a ready-made candidate for this in the form of

his former business partner and the director of his election

campaign, Laurent Salvador Lamothe. As head of his own company

Global Voice, Lamothe had extensive experience of how profitable

such levy systems could be in various African countries.

Profitable for him as well as his client states, that is.

Renowned as a tough negotiator, Lamothe’s company had reportedly

been getting up to 50% of the value of all levies collected in

such schemes.

Almost nothing was heard of the

Fund until September 2011, when the President’s Education

minister-designate, Gaston Merisier, stated that the FNE had

amassed $28 million. However, it soon emerged that only $2

million of this, the share from money transfers, was with the

BUH. The remaining $26 million was credited to an account in the

name of CONATEL, the national telecoms regulator, and as such

closed to even the most elemental external scrutiny.

The lack of any basic

accountability or transparency meant that serious discrepancies

in consequent figures as to the value of the Fund cited by

Diaspora news organisations, members of the Haitian Senate,

civil society organisations, and even the head of Digicel,

Haiti’s largest telecoms operator, tax payer and employer, could

not be reconciled.

In January 2012, mounting

concern forced Martelly to address the issue of the FNE,

declaring: “Not one cent of the money has been touched... the

people around me are not thieves... the money is so secure I

can’t tell you anything about it.” To ensure nothing was

revealed “about it,” government lawyers began threatening the

news outlets asking questions.

Meanwhile, Digicel’s concern

rapidly evaporated, perhaps their energies were focused on their

imminent takeover of their only sizeable rival in Haiti, Voilà –

a transaction that attracted minimal regulatory interference

from CONATEL, despite it granting them an effective cellphone

monopoly.

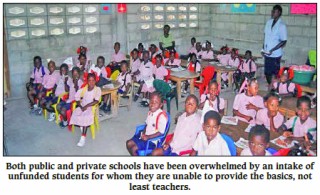

Sadly, one thing does confirm

Martelly’s assertion that none of the Fund has actually been

disbursed: there has been no discernable boost to the Haitian

education system. While a number of pupils who had not

previously attended school are now getting ‘free education’

(albeit far fewer than the government claims, as its figures

include pupils already in free education), both public and

private schools have been overwhelmed by an intake of unfunded

students for whom they are unable to provide the basics, not

least teachers.

Nothing has changed in the year

since Martelly’s only comment on the Fund. The start of the

2012-2013 school year was again delayed by a full month due to

lack of funding. Teachers continue to demonstrate in pursuit of

months of unpaid wages. The original lack of a legal framework

in setting up the FNE means its proceeds cannot be handed to the

Ministry of Education. That state of affairs has now become

institutionalized, the failure to hold elections for a number of

Senate seats means it remains inquorate and thus

constitutionally unable to ratify any retroactive legal

framework.

But what of the actual value of

the Fund? While in Florida in December 2012, where he had

somewhat bizarrely decided to make his ‘State of the Nation’

(Haiti, not the United States) address, Martelly told the Miami

Herald that the FNE was worth $16 million. That was dramatically

at odds with the estimated revenue at its launch, which after 16

months would have been $136 million, not to mention a statement

by CONATEL on 31 December, which put the Fund’s value at $81

million.

Is the discrepancy explained by

the level of Global Voice’s percentage take for collecting the

levies? If so, either of the figures above would mean, that

percentage is well above the generous 50% Global Voice has

pocketed elsewhere in the world. Someone who would know has,

since the inception of the Fund, been promoted to Prime Minister

of Haiti, namely Laurent Lamothe.

Worse still, perhaps, is the

fund being used for other purposes, governmental or

non-governmental? Presidential slush funds are hardly unknown in

Haiti, in fact historically they have been the norm. It was just

this sort of transparency vacuum that allowed the national

Treasury to become the personal purse of the Duvaliers. And as

Haitians are now asking: if this level of opacity and poor

governance surrounds such a flagship as the FNE, what else is

going on in even less scrutinized parts of this administration?

First published in Haiti Briefing, Number 73, February

2013,

www.haitisupportgroup.org

|