|

by Yves Pierre-Louis

& Kim Ives by Yves Pierre-Louis

& Kim Ives

On Feb. 28, 2013, former Haitian

dictator Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier had to show up at the

Port-au-Prince Appeals Court to hear various charges against him

for crimes against humanity. After not responding to three

previous summonses in February, the former "President for Life"

had to bow to the court’s authority or risk arrest for contempt.

Duvalier is due to report to court again on

Mar. 7, but his lawyer claims that he has been admitted into an

unspecified hospital with an unspecified sickness.

Nonetheless, many suspect that the hearings summoning

Duvalier are nothing more than "show business" aimed at

eventually rubber-stamping the Jan. 30, 2012 finding of

examining magistrate Jean Carvès. He ruled that the statue of

limitations has expired for prosecuting Duvalier for his human

rights crimes. These hearings are for an appeal to overturn that

ruling.

Duvalier ruled Haiti with an iron fist from 1971 to 1986,

during which time tens of thousands were extrajudicially killed,

imprisoned, exiled, or disappeared.

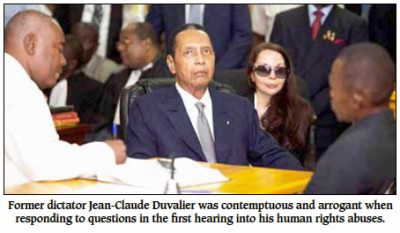

With many of his victims in the audience, Duvalier responded

to questions from members of the Court, the prosecution, the

plaintiffs, and defense counsel.

When the court asked about "repression, torture, beatings,

crimes against humanity, political killings, and human rights

violations" under his regime, Duvalier dead panned that "every

time an anomaly was reported to me, I intervened so that justice

could be done. I want to stress that I sent a letter to all

department commanders, to all section chiefs, asking them to

strictly apply the law around the country, and these directives

also applied to the Corps of the Volunteers for National

Security," better known as the infamous Tontons Macoutes, a

paramilitary militia which acted as the eyes, ears, and fists of

the Duvalier regime.

Asked again later about "murders, political imprisonment,

summary execution under your government, and forcing people into

exile," Duvalier replied: "Murders exist in all countries. I did

not intervene in police activities... As for imprisonment,

whenever such cases occurred, I intervened to stop abuses being

committed."

Duvalier never betrayed a trace of remorse or regret, arguing

that "I did everything to ensure a better life for my

countrymen... I'm not saying that life was rosy, but at least

people could live decently."

Returning to Haiti in January 2011, "I found a ruined

country, with boundless corruption that hinders the development

of this country," Duvalier said. "And on my return, it’s my turn

to ask: what have you done to my country?"

He suggested that he was close to journalist Jean Léopold

Dominique (assassinated in 2000), "who accompanied me often in

my inspections in the provinces" and that he helped Dominique

obtain his radio station, Radio Haïti.

Former soccer star Robert "Bobby" Duval, the founder of the

Haitian League of Former Political Prisoners (LAPPH), was also

in the courtroom as one of the plaintiffs appealing Judge Carvès

Jean’s ruling. Duval spent 17 months imprisoned in the infamous

Fort Dimanche prison without charges. But Duvalier claimed that

Duval "was arrested for subversive activities," saying that

"during a search at the François Duvalier airport, we found

weapons in his possession and he was released a few years later

by an act of clemency by the Head of State." Duvalier claimed

that Duval’s suit against him "is a real joke" and that Duval

"was treated well" and that "a family member brought him food

three times a day." Duval almost died from starvation and

disease in Fort Dimanche.

Asked what he thought about the charges against him, Duvalier

said "it makes me laugh" because people are just "inventing

fantasies."

The hearing lasted more than three hours, after which

Duvalier’s victims and representatives of human rights

organizations said they were satisfied and encouraged that the

Appeals Court judges were not intimidated by pressure from the

government of neo-Duvalierist president Michel Martelly. They

said they felt more determined than ever to talk about the

suffering and torment caused by the murder, imprisonment,

disappearances, and other crimes committed under Duvalier’s

dictatorship. They were also galled by Baby Doc’s contemptuous

attitude during the hearing.

After the hearing, Bobby Duval scoffed at Duvalier’s

assertion that he had been arrested for illegal possession of

firearms. Of the 13 Haitian political prisoners whom Amnesty

International championed at that time in the late 1970s, Duval

is one of the three survivors. "Their goal was to kill me," he

said, adding that he would not have survived much longer in

prison.

Henry Faustin was another former political prisoner who

attended the trial. Arrested on Jun. 15, 1976, Faustin spent two

months in a dungeon in the Dessalines Barracks (another

political prison under Duvalier, located behind the National

Palace). Only 20 years old, Faustin was then transferred for

another 16 months (until December 1977) to Fort Dimanche. "Fort

Dimanche was not child's play," he said. "You arrived there as a

prisoner, with clothes, but then they stripped you naked as a

worm."

International human rights organizations are following the

Duvalier hearings closely. "If someone like Duvalier is not

judged, how can one judge someone who has stolen a chicken to

feed his family?" asked Reed Brody of Human Rights Watch. "How

do you establish the rule of law when he who is accused of the

worst crimes gets away with it? But Haiti has always been

considered an exception. Moreover it is interesting to see that

the big countries like France and the United States have never

requested that Duvalier be tried, because they have disdain for

Haiti. Haiti is not entitled to justice. It's good enough if

Haiti just gets a little to eat, or if the population has a

little shelter. They don’t make the link between the lack of

justice for the vast majority and the lack of social justice as

well." |