|

by Isabeau Doucet

I

contracted cholera two years ago by the breezy beaches of Port

Salut, while attempting to escape burnout, a broken heart, and

the lingering pangs of Dengue fever in Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s

capital. I

contracted cholera two years ago by the breezy beaches of Port

Salut, while attempting to escape burnout, a broken heart, and

the lingering pangs of Dengue fever in Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s

capital.

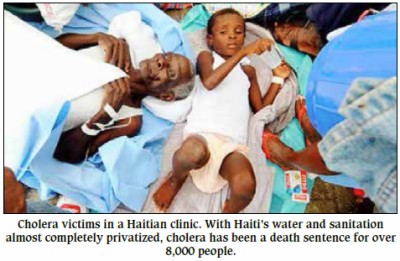

Cholera’s not a whole lot different from food poisoning and is

no big deal if you have a clean toilet, potable water, know how

to treat it, and aren’t malnourished.

But in

hunger-wracked Haiti, where there is no sewage system and where

water and sanitation are almost completely privatized, cholera

has been a death sentence for over 8,000 people. According to a

host of scientific studies (including the UN’s own

investigators), the South Asian strain of the disease was likely

imported by UN troops from Nepal in October 2010. Having

sickened over 640,000, it is now the worst cholera epidemic in

modern history.

A week before the

long-delayed release of an international $2.2 billion 10-year

eliminate-cholera plan at the end of February, the UN rejected

outright a legal claim filed by over 5,000 cholera victims

seeking financial compensation, an apology for the UN’s gross

negligence, and a commitment that the world body rebuild Haiti’s

water and sanitation infrastructure.

Invoking immunity

under its1946 convention, the UN snubbed the suit as “not

receivable.” It has not apologized and has committed only 1%

($23.5 million) to the plan, recommending Haiti get the rest

from the “private sector” or from “major venture philanthropist

individuals,” according to Nigel Fisher, the new head of the UN

military occupation force in Haiti known as MINUSTAH.

"Combating water

born diseases, cholera, is actually a good investment if you

want to attract investors," Fisher added.

With some 9,000

armed soldiers and police officers, MINUSTAH had an annual

budget of over $800 million last year. Its current one-year

mandate ends on Oct. 15, 2013.

In a country

where nearly 80% of people live on less that $2 a day, the

water-and-sanitation-access-for-profit model has left over 80%

without adequate sanitation and nearly a third without potable

water.

"When

you look at the price of a bag of water, supposedly treated, it

costs more to buy a gallon of water when you're poor than a

gallon of diesel fuel," said veteran political activist Patrick Elie, looking at water vendors weave through traffic and crowds

to sell as many 300ml 5 cent bags of iced water as possible

before they turned hot under Haiti’s blistering sun.

Those in tent

camps and shanties who can’t pay for a toilet, defecate into

plastic bags that end up in the nearest canal or ravine.

While

the poorest of the poor get their water and get rid of their

waste in plastic bags, the rest are subject to the pay-as-you-go

free-market chaos of water and waste tanker-trucks, run almost

entirely by the local and international NGO private sector. A

sharp rise in petrol’s price, if some event, say, changes Hugo

Chavez's PetroCaribe deal under which Haiti gets cheap oil

largely on credit, could quickly deepen Haiti's water and

sanitation crisis.

DINEPA, Haiti’s National Water and Sanitation Agency founded in

2008, says around a dozen private companies collect and dispose

of sewage along with an unregistered number of manual merchant

toilet cleaners, know as “bayakou.” DINEPA could not

answer how many private water provision companies operate in

Haiti and directed the query to the Ministry of Commerce and

Industry, which sent the question back to DINEPA. There is

evidently no registration of water companies and no state

regulation of water quality.

Haiti is one of

the few countries in the world where water security has

deteriorated since the implementation in 2000 of the Millennium

Development Goals, while, since 2004, the UN has maintained a

multi-billion dollar military occupation in a country with no

war and one of the lowest homicide rates in the region.

Jon

Andrus, Deputy Director of the Pan American Health Organization

(PAHO), concedes that the privatization of Haiti’s water and

sanitation has threatened Haiti’s most vulnerable people and

that PAHO and partners "have failed for decades to reverse that

situation."

Andrus is

optimistic about the new plan having seen first hand the

eradication of polio, rubella, and measles in some of the

poorest parts of the world, despite “naysayers” even at high

levels of government.

The challenge of

raising $2.2 billion in the face of international donor fatigue

is not small, even though only 1% of post-earthquake funds

actually went to the Haitian government, and international

donors still owe Haiti $2.5 billion in unfulfilled pledges. The

U.S. alone has yet to come through on $650 million pledged in

post-earthquake “build back better” funds, which could neatly

cover the next two years of the cholera eradication plan.

“I

can’t think of another country where they built the

infrastructure from the ground up in an emergency context” said

Dr. Daniele Lantagne, a U.S. cholera expert specializing in

emergency water and sanitation interventions in developing

countries. Lantagne is one of the leading scientists who

concluded the UN’s camp of Nepalese soldiers in Mirebalais on

Haiti’s Central Plateau was “the most likely source of the

introduction of cholera into Haiti.”

On

Feb. 27, 2013, the UN billed the 10-year cholera eradication

plan as its own (the Haitian and Dominican governments had

originally proposed it in January 2012). Yann Libessart, the

communication officer of Doctors Without Borders (MSF), was not

impressed by the lofty rhetoric of UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon

and others that day. Only $238 million, barely half of the

plan’s funding for the next two years, has been scraped

together, most of that ($215 million) coming from money already

pledged during the Mar. 31, 2010 post-earthquake UN conference.

Meanwhile cholera treatment centers which MSF passed on to the

government are currently “degenerating” into “contamination

zones,” he says. When asked who should fund the plan, Libessart

is blunt: “the people who are responsible for the introduction

of the disease into the country, for example.”

The

same sentiment was expressed by Dr. Ralph Ternier, Partners In

Health Director of Community Care and Support in the Central

Plateau, where cholera originated and persists today at a rate

double the national average.

“What’s important for this kind of institution is their image,”

said Ternier, not surprised by the UN’s parsimony on cholera

relief. “The fact that they’d give more money would mean they

are guilty.”

Emergency funds for cholera - only 2.5% of which ever went to

the Haitian government - dried up in January. Most NGOs have

left and the funding vacuum is squeezing DINEPA, putting the

water and sanitation jobs of two dozen qualified Haitians on the

firing line.

In

January, white UN sewage trucks could be seen offloading their

contents into the tailing ponds of Haiti’s first sewage

treatment plant in Morne à Cabrit. Now, that plant has been

closed for maintenance due to lack of operational funds. It

opened only 18 months ago.

Since

sewage treatment is central to stopping cholera, why aren’t

international funds forthcoming? “It beats me,” says Wilson

Etienne, a DINEPA official who oversaw the the building of the

treatment site.

DINEPA still aims to open two dozen treatment sites, one in each

urban center, but the only business model Etienne foresees

making this possible is one that charges $4 per cubic meter of

human waste.

For

now, the Morne à Cabrit plant remains closed. “This site should

have been something Haitians could be really proud of,” laments

Etienne, shaking his head.

An earlier version of this article was published in The Nation. |