|

by Kim Ives

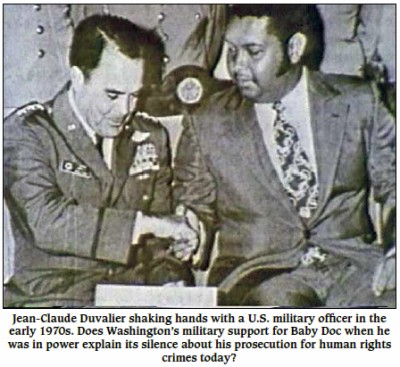

A chorus of outrage is building against

former Haitian president Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier as he

sits in the dock of a Haitian court, charged with crimes against

humanity during his 15-year rule. However, the U.S. government

remains strangely and completely silent. A 40-year-old trove of

diplomatic cables, newly unearthed by WikiLeaks, helps explain

why.

Around midnight in the early morning hours

of Jul. 23, 1973, a fire broke out in the packed armory of

Haitian dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier’s National Palace.

Almost immediately,

“President-for-Life” Duvalier and his Army Chief of Staff,

General Claude Raymond, telephoned the U.S. Embassy’s Deputy

Chief of Mission, Thomas J. Corcoran, to tell him about the fire

and ask for U.S. assistance in putting it out.

The destruction of Haiti’s

large weapons cache became, in the following days, the perfect

excuse to resume the sale of military weapons as well as

military aid and training to the Duvalier dictatorship, after it

had been halted during the 1960s under the notorious regime of

François “Papa Doc” Duvalier.

Haïti Liberté has been

able to reconstruct a clear picture of this pivotal historical

moment thanks to a new website constructed by WikiLeaks called

the Public Library of U.S. Diplomacy or PlusD. The site

enables searching of over 1.7 million State Department cables

from 1973 to 1976 which had been declassified and stored in the

U.S. National Archives, but which were all but inaccessible due

to the form in which they were kept.

Haïti Liberté is one of

18 media partners worldwide to which WikiLeaks provided

exclusive access to the PlusD search engine in early March,

prior to its unveiling for public use on Apr. 8. This article is

one of several which Haïti Liberté is planning based on

the cables from the 1970s.

“General Raymond and President

Duvalier telephoned me at 0245 [2:45 a.m.] to report fire in

National Palace and to request fire extinguishers which we

dispatched,” Corcoran explained in a

Jul. 23, 1973 Confidential

cable. “At about 0325 Foreign Minister [Adrien] Raymond informed

me fire was spreading throughout ammunition storage including

small arms and artillery ammo and beyond control of local

firefighting facilities.”

The U.S. immediately deployed a

team of nine military fire-fighters from its naval base at

Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. They “acted without regard for their

personal safety in fighting the fire in an area in which a large

variety of explosive ordnance had been stored and exposed to

intense heat over a period of hours,” Corcoran wrote in a

Jul.

27, 1973 cable commending their valor.

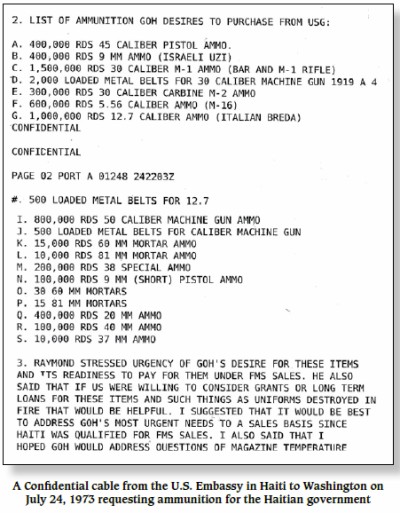

On Jul. 24, 1973, the day

immediately after the fire, Foreign Minister Raymond “summoned”

Corcoran and “presented [him] a list of ammunition and mortars

which GOH [the Government of Haiti] urgently desires to purchase

for the ‘maintenance of public peace, the tranquillity of

families and protection of property.’”

Adrien

Raymond, “on instructions of

President Jean-Claude Duvalier,”

urgently requested millions of

rounds of ammunition for Haiti’s Army. Among the largest items

on the long list were 1.5 million 30 caliber rounds for M-1

rifles, 800,000 rounds for 50 caliber machine guns, 600,000 5.56

mm rounds for M-16 automatic rifles, and 400,000 9mm rounds for

Uzi submachine guns. Duvalier also wanted dozens of mortars and

tens of thousands of mortar shells.

The Haitian Army had never

waged war against any enemy other than the Haitian people.

Nonetheless, Corcoran and the U.S. Embassy’s military attaché

called the list “reasonable” and “strongly recommend[ed]

approval of sale,” the cable said.

In the following weeks,

Haiti’s

military laundry list would grow in length and breadth, asking

not just for more ammunition but also for weapons and supplies,

including 38 and 45 caliber handguns, M-1 rifles, M-2 carbines,

30 and 50 mm machine guns, 60 and 81 mm mortars, grenade

launchers, cartridge belts, and high-capacity ammo clips.

On Jul. 25, 1973, Corcoran sent

another Confidential cable where he encouraged the State and

Defense Departments “to take quickest possible action” and make

an “extraordinary effort to expedite paper work” to reply

favorably to Duvalier’s request because, among other reasons,

“the Haitian Government is prepared to pay for its requirements,

and there is no reason why the US should not get the sale.” (Not

long before, Haiti had bought weapons from Israel and Jordan, as

well as “from ‘fast-buck’ private arms dealers,” according to

Corcoran.)

Furthermore, Duvalier’s

“request seems an excellent opportunity to strengthen U.S.

influence even more with the GOH... and to win the goodwill of

individual Haitian military officers,” Corcoran wrote in the

cable.

The U.S. had curtailed military

aid and sales to Haiti after François Duvalier expelled a U.S.

Marine Mission from the country in 1963. But following Papa

Doc’s death in April 1971, his son “Baby Doc” inherited the

“Presidency for Life” and began to repair and improve relations

with the U.S., from which he wanted aid and investment.

Indeed, the sale was approved

and the “GOH delivered to [the U.S.] Embassy Sept. 19, 1973

check no. 163211 drawn on National Bank of Republic of Haiti

same date payable to USAFSA [United States Army Forces in South

America] in amount of dollars $273,411.40,” Corcoran wrote in a

Sep. 19, 1973 cable. The sale was equivalent to over $1.4

million in 2013 dollars.

Nonetheless, the U.S. was

worried about appearances, and Corcoran wrote in an

Aug. 17,

1973 cable that “no, repeat no, USG [U.S. Government] aircraft

delivery [is] contemplated.” Instead the guns and ammo arrived

on two Pan Am charter flights on Sep. 26 and Oct. 1, 1973, the

cables show.

Around the same time, the U.S.

Embassy was also negotiating with the regime for the sale of six

“Cadillac-Gage commando armored cars,” two of which would be

used for the Leopards, an elite counter-insurgency unit of the

Haitian army.

The U.S. wanted to proceed with

the sale of just four cars, the request for which had been made

in June, before the armory fire. The Embassy wanted to finish

with the pending ammunition and weapons sale “before addressing

[the] problem of [the] other two cars,” but Duvalier had

threatened to take his business elsewhere, namely to the French,

Corcoran explained in an

Aug. 31, 1973 cable. He recommended

that “that State/Defense [Departments] reply gently to implied

threat to transfer order to French firm that financial outlay of

that sort to French company at time U.S. giving economic

assistance to Haiti might raise all sorts of questions.”

Military aid was also being

resumed in this period. The “Embassy can understand Haiti's

exclusion from the list of countries eligible for grant military

training in the 1960s, owing to political conditions prevailing

at that time,” Corcoran argued in a

Nov. 23, 1973 cable.

“However, times in Haiti have changed. The country has a new,

young president moving in some positive new directions.” He

claimed that “in the past few years, repression has been

markedly and genuinely eased in Haiti” and that the government

was showing “political restraint” and “a clear desire to do more

for the economic development of the country.”

Most importantly, “in

international organizations, the new government in Haiti has

been a dependable, good friend of the U.S., for whatever that is

worth,” Corcoran wrote. “All these are positive tendencies which

it seems to us should be encouraged.”

This was “why we believe some

grant military training for Haiti is very much in our

interests,” because, among other things, it provided “the

opportunity to establish some influence with the whole

generation of younger Haitian military officers who know nothing

of the U.S..”

“In sum,” Corcoran concluded,

“it seems illogical that Haiti... should still be singled out

for total exclusion from grant training programs enjoyed by

nearly every other nation of the hemisphere for many years --

training which will contribute substantially to advancing a

number of our important interests in the region.”

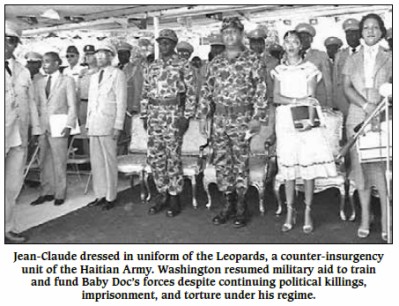

Indeed, U.S. military aid was

resumed, specifically to train units like the Leopards, which

was described by the National Coalition for Haitian Rights in a

1986 report as“particularly brutal in dealing with civilians.”

Researcher Jeb Sprague explains

in his new book “Paramilitarism and the Assault on Democracy in

Haiti” that the Leopards were trained and equipped “by former

U.S. marine instructors who were working through a company (Aerotrade

International and Aerotrade Inc) under contract with the CIA and

signed off by the U.S. Department of State. Baby Doc himself

trained with the Leopards, forming particularly close bonds with

some in the force. A U.S. military attaché bragged that the

creation of the force had been his idea. Aerotrade’s CEO, James

Byers, interviewed on camera, explained that he had ‘no trouble

exporting massive quantities of arms. The State Department

signed off on the licenses, and the CIA had copies of all the

contracts. M-16 fully automatic weapons, thousands and thousands

of rounds of ammunition, patrol boats, T-28 aircraft, Sikorsky

helicopters. Thirty-caliber machine guns. Fifty-caliber machine

guns. Mortars. Twenty-millimeter rapid-fire cannons. Armored

troop carriers.’ A handful of veterans from this force would

later serve, off and on, as key figures in various paramilitary

forces” which the U.S. used to carry out and maintain coups

against the governments of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in

1991 and 2004.

Jean-Claude Duvalier, who

returned to Haiti in January 2011 from a 25 year golden exile in

France, is now technically under house arrest in Haiti. An

appeals court is receiving testimony and evidence from witnesses

charging that Duvalier must be tried for crimes against

humanity. Haitian and international human rights groups

have

documented hundreds of cases of torture and extrajudicial

killings and imprisonments under Baby Doc’s 15 year rule from

1971 to 1986. In January 2012, investigating judge Carves Jean

dismissed the human rights charges against Duvalier, arguing

that the statute of limitations had expired. The appeals court

may overrule that decision.

About 7,000 of the 1.7 million

secret diplomatic cables from 1973 to 1976 deal with Haiti. The

cables “were reviewed by the United States Department of State's

systematic 25-year declassification process,” WikiLeaks explains

on its PlusD website. The cables were then “either declassified

or kept classified with some or all of the metadata records

declassified” and then “subject to an additional review by the

National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).” Those

cables released then “ were placed as individual PDFs at the

National Archives as part of their Central Foreign Policy Files

collection.”

However, the cables in their

PDF form “are actually quite difficult to get to for the general

public,” explained Kristinn Hrafnsson, a spokesperson for

WikiLeaks and a former Icelandic investigative journalist, to

Democracy Now on Apr. 8. “It’s very hard to access them. So, in

our view, the inaccessibility and the difficulty of accessing

them is a form of secrecy... so we found it important to get it

to the general public in a good searchable database.”

Twenty-five year old U.S.

classified documents are supposed to be reviewed and

declassified every year. The public should therefore be able to

view classified documents as late as 1988. However, the

declassification process has only been done until 1976, meaning

it is 12 years behind schedule.

Another reason that WikiLeaks

established the PlusD database is because “there has been a

trend in the last decade and a half to reverse previously

declassified policy,” Hrafnsson explained. “A policy set out,

for example, by Clinton in the mid-'90s was, a few years later

under Bush, is reversed. It was revealed in 2006, for example,

that over 55,000 documents that were previously available had

been reclassified by the demand of the CIA and other agencies.

And it is known that this program continued at least until 2009.

So, it is very worrying when the government actually starts

taking back behind the veil of secrecy what was previously

available.” The PlusD database cannot be snatched back behind

the veil.

The 1973 to 1976 cables cover

the period that infamous Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was

in office under both Presidents Richard Nixon and then Gerald

Ford. WikiLeaks has therefore dubbed the trove the “Kissinger

Cables.” (After he left his post, Kissinger and his wife visited

Duvalier in Haiti.)

In 2011, WikiLeaks provided

Haïti Liberté exclusively with about 2,000 secret U.S.

cables related to Haiti dating from 2003 to 2010. They came from

a larger 250,000-cable trove, known as “Cablegate,” which was

anonymously provided to WikiLeaks by U.S. Corp. Bradley Manning.

He has been imprisoned in “pre-trial detention” some 1,050 days

under torture-like conditions. He is being court-martialed and

may be charged with treason, which can carry the death penalty.

There is a world-wide movement denouncing the U.S. government’s

treatment of Manning, who also gave to WikiLeaks

a video showing

a U.S. Apache helicopter gunning down 12 people in Iraq in

2007, including two Reuters journalists.

With the release of PlusD and the “Kissinger

Cables,” WikiLeaks has once again provided journalists and

people around the world a glimpse into the shrouded world of

U.S. foreign policy. While Top Secret cables are not available,

the thousands of formerly Secret and Confidential cables from

the 1970s provide a clear look into how the State Department

fashioned its rationales for many outrageous policies during

that period, like the resumption of military aid to an

unelected, corrupt, and repressive dictator like Jean-Claude

Duvalier. |