|

by Jeb Sprague

President

Michel Martelly now stands poised to institutionalize as a

standing army the very paramilitary forces which helped

overthrow Haiti’s elected government in 1991 and 2004. President

Michel Martelly now stands poised to institutionalize as a

standing army the very paramilitary forces which helped

overthrow Haiti’s elected government in 1991 and 2004.

Jeb Sprague’s

new book, Paramilitarism and the Assault on Democracy in

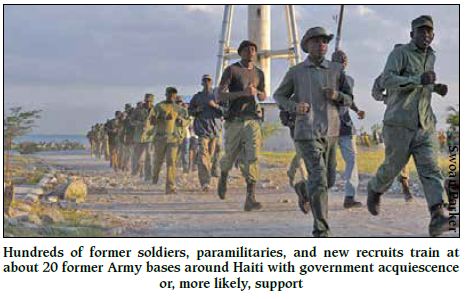

Haiti, is just out and not a moment too soon. Paramilitaries

are being trained and housed on close to 20 former Haitian Army

bases around Haiti, with a wink and a nod (if not more) from

Martelly’s government.

“Former soldiers and

death-squad members were set up on 23 bases around Haiti,”

explained Sen. Moïse Jean-Charles in a July interview with

Haïti Liberté. “In the face of international criticism, the

government made a big production of closing down four of those

bases earlier this year. But what about the other 19 de facto

bases? They are still functioning, and Martelly knows it.

Martelly is behind it.”

This week we present the

introduction of Sprague’s important new book which professor and

author Robert Fatton called a “must-read not only for

Haitianists, but also for anyone interested in the processes of

political destabilization and popular disempowerment.”

This autumn, Sprague will make

a speaking tour for the book’s release throughout Canada and the

U.S.. We publish the schedule for that tour alongside the

article.

His

right eye blinked furiously, swollen and red; he continued to

rub it. In Kreyòl, he demanded to know how I had found him: “Kote w ou jwenn nimewo telefòn mwen?”

(Where did you get my phone number?); “Pou kiyès wap travay?”

(Who are you working for?), he said as he stared at me with

suspicion.

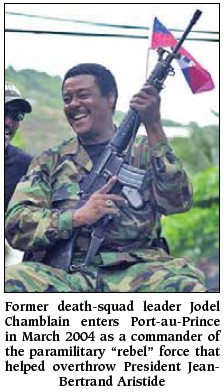

Louis-Jodel Chamblain, the man

sitting across from me, had been a commander of the paramilitary

force (paramilitaries are irregular armed organizations backed

by sectors of the upper class) known as the Revolutionary Front

for the Liberation of Haiti (also known as the Front for the

National Liberation and Reconstruction of Haiti, or FLRN). He

explained to me that he had taken up his position during an

“uprising” in early 2004 against Haiti’s government. He was also

a cofounder in the mid–1990s of the Front for the Advancement

and Progress of Haiti (FRAPH) death squads. According to Human

Rights Watch, the FRAPH took part in the killing of at least

4,000 people as well as in thousands of rapes and other acts of

torture. Before cofounding the FRAPH, Chamblain had served with

the Tonton Macoutes, the infamous paramilitary arm of the

Duvalier dictatorship, which according to human rights

organizations was responsible for killing tens of thousands of

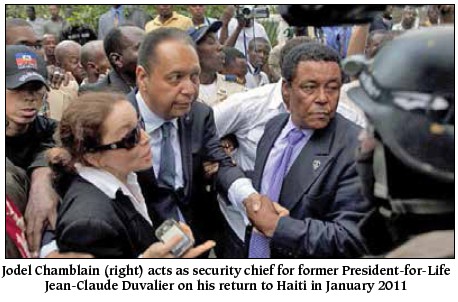

people and victimizing many more. In early 2011, Chamblain would

head up security for Jean-Claude Duvalier when the former

dictator made a surprise return to Haiti.

Having interviewed and met some

of the victims and victims’ family members that Chamblain and

his fellow paramilitaries had brutalized, I knew what he was

capable of doing. I was afraid of him, but I thought speaking

with him could potentially reveal important information. Might

he let something slip? Who had supported the paramilitaries in

Haiti? What would he reveal about the involvement of my

government, that of the United States, or of local wealthy

business leaders? We sat on a veranda at the luxurious Hotel Ibo

Lele, on a steep Pétion-Ville hillside overlooking

Port-au-Prince. It was apparent that the hotel staff knew

Chamblain well; they brought us lemonade as we talked. Sweat

poured from my forehead as I tape-recorded an interview that

lasted for two long hours. It was clear that Chamblain had been

staying at the hotel for some time, even befriending UN

officials staying at the sunny resort.

When the interview was done, I

and a Haitian friend who had accompanied me for the interview

sought to exit quickly. We picked up our things. But Chamblain,

refusing to take no for an answer, drove us down the hill into

the city; he wanted to know where we were staying. Soon, making

up some excuse to get out of the car, we waved to two

moto-taxis. Zooming down a lively boulevard filled with

colorfully decorated bus and pickup truck transports known as

tap-taps, weaving around jammed traffic, we looked back over our

shoulders making sure that Chamblain was not following us in his

white jeep. Ironically, I was staying for a few nights at the

Izméry house (better known as the Matthew 25 house) in the

neighborhood of Delmas 33. With an adjacent park where the local

children play, it was the former home of the progressive Haitian

businessman Antoine Izméry, who had been assassinated by

paramilitaries years prior. Chamblain had formerly been

convicted of organizing the killing. Adding greatly to our

fears, just two days prior, a human rights leader and dear

friend, Lovinsky Pierre Antoine, had disappeared. Because

Lovinsky was one of the major figures of Haiti’s grassroots

human rights movement and one of the longtime opponents of the

ex-military and paramilitary criminals such as Chamblain, some

believed that a rightist hit squad was responsible.

This article for Haïti

Liberté, which is an abridged version of the introduction to

Paramilitarism and the Assault on Democracy in Haiti,

seeks to introduce the reader to the historical and sociological

context through which paramilitaries, led by people such as

Chamblain, struck a major blow against democracy and the Haitian

people at the beginning of the 21st century.

A Brief Overview of

Paramilitarism in Haiti

The poor living on the island dubbed

Hispañola (where today sit Haiti and the Dominican Republic)

have long been the targets of political violence. With the

Spanish conquest of the Caribbean, begun by Columbus in 1492,

the indigenous inhabitants — the Arawak — were subjected to

genocide, slavery, and infectious disease. The Arawak included

different groups, such as Taínos who populated much of the

Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. At least one million Taínos

are believed to have been living on the island where Columbus

arrived. Anthropologist and medical doctor Paul Farmer explains

that the entire Arawak population in the region diminished in

number from as many as 8 million when Columbus arrived to an

estimated 50,000 by 1510 and could be counted in the hundreds by

1540. By the late 1600s, the indigenous inhabitants of Hispañola

were completely gone.

With the conquistadors came

sugarcane, brought originally to the island by Christopher

Columbus on his second voyage. The production of sugarcane was

taken to new heights in Saint Domingue on the western side of

the island, which was handed over in a treaty to France in 1697.

To harvest the sugarcane, African slaves were brought to the

colony, imprisoned in the cargo holds of sea vessels.

Less than a century later, by

1789, the colony was supplying three-quarters of the world’s

sugar. It generated more wealth for France than all of the 13

North American colonies produced for Great Britain. At this

time, two-thirds of Saint Domingue’s half-million slaves had

been born in Africa; the majority could remember a time when

they were not slaves at all, or at least not slaves to whites.

Brutal conditions caused the deaths of one out of every three

slaves every three years.

Over the following years, a

historic slave revolution took place, after which a

post-colonial social order congealed. But toward the end of the

19th century, ramped up foreign military intervention

occurred. With the formation of Haiti’s modern army under the

U.S. occupation of the country between 1915-1934, the U.S. made

sure to leave only after ensuring the new military force could

be relied on to continue the occupation by proxy. In the early

1960s, U.S. Marines trained the Tonton Macoutes, the dreaded

paramilitary force of then dictator Francois “Papa Doc”

Duvalier. The institutionalization of this paramilitary force

took place at a time in which the cold war (and events in the

Caribbean) were increasingly present in the minds of U.S. policy

makers and dominant social groups active in the region. As

Duvalier’s son, Jean-Claude, took over in 1971, former U.S.

marine instructors trained and equipped an elite military force

(the Leopards). They worked through a Miami company under CIA

contract and with U.S. State Department oversight. The brutal

role of paramilitaries in Haiti throughout the late 1950s and

continuing on throughout the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s (as well as

their historical antecedents) is documented in Chapter 1 of my

book.

The phenomenon of

paramilitarism in crushing the Haitian people’s experiment in

popular democracy begins in the last quarter of the 20th

century, when democratic struggles for social justice and

inclusion were taking place around the world. Although fierce

opposition crushed most of these, the Haitian struggle was one

that endured, albeit at a tremendous cost. Many leftist or

left-leaning movements and their political parties in the

Caribbean and Central America had been attacked, divided,

neutralized, or subdued: the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, the

People’s National Party (PNP) in Jamaica, the People’s

Revolutionary Government (PRG) in Grenada, and the Farabundo

Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) in El Salvador. But

following decades of kleptocratic dictators and struggles

against them by movements from below in Haiti, in early 1991,

for the first time in the country’s history, organizers of a

mass-based, pro-democracy political movement (that would become

known as Lavalas, or “the flood”) were propelled to state power

through elections, with a young priest, Jean-Bertrand Aristide,

becoming the country’s first democratically elected president.

In the post-Cold War era, after

the fall of the Soviet Union and its support for liberation

struggles, and as the world underwent capitalist globalization

and neoliberal regimes came to power across the hemisphere, in

Haiti some of the poorest people bucked the trend and struggled

for an alternative path. Their attempts at democracy provoked

two bloody coups: the first in 1991 and then another in 2004.

Both coups were backed by an array of elites and armed groups.

Haiti’s popular movement and

its leadership were still recovering from the impact of the 1991

coup and the three years of brutal military rule that followed

when, in late 2000, a campaign that would eventually drive Fanmi

Lavalas (FL) and its leader Jean-Bertrand Aristide from power in

2004, began to gather momentum. A variety of coercive strategies

were used by various upper-class sectors to neutralize the

potential for (often slow, but steady) popular democratic

reforms in Haiti. These strategies were refined in response to

on-the-ground developments but can also be seen in light of

major shifts occurring through the era of global capitalism.

Paramilitary violence has been used as a tool for repressing the

popular classes (workers, peasants, slum dwellers, street

vendors, the unemployed, and others who formed the bulk of

support for Fanmi Lavalas classes and social groups not among

Haiti’s elite of large landholders and big business owners), and

has, in its most contemporary form, been utilized to benefit, at

different times, dominant local and transnational social

groups and classes.

One may ask why some dominant

groups (and officials from governments such as those of the

United States, France, and Canada) care — as they obviously have

— about stifling a pro-democracy movement in so small and poor a

country. The simplest — and bluntest — answer has been provided

by Noam Chomsky. He likens the elite networks that undergird

global capitalism to a mafia that does not allow even the

smallest and most inconsequential shopkeeper to show open

defiance. Defiance can inspire others and must be crushed one

way or another, one such way being paramilitary violence. From

this point of view, like intelligent mafia dons, many elites

will not necessarily deploy violence as a first resort. But when

paramilitary violence is deployed, what are the processes

through which this occurs? Furthermore, how do elites differ in

such tactics and motivations — sometimes creating contradictions

that pose difficulties for them?

Over time, some have become

aware of the atrocities perpetrated by paramilitaries and

various “security” forces, but it has been extremely difficult

for information on paramilitary violence to make its way into

the mainstream media and reach larger audiences. Media coverage

of political violence against the poor is often slim to nil. The

struggle against paramilitary violence has occurred mostly

through the struggle of Haiti’s pro-democracy movement itself.

In addition to this, the prying eyes of dedicated grassroots

media and documentarians, as well as the campaigns of some human

rights activists and lawyers, have made it more difficult for

paramilitaries (and other armed groups) to operate so openly in

confined urban spaces without word getting out about their

crimes. To prevent the embarrassing circumstances that these

kinds of situations create for dominant groups (who have often

allied with anti-democratic regimes and at times allowed,

sponsored, or done nothing to stop paramilitary violence),

transnationally oriented elites have promoted what has been

called “polyarchy.”

Sociologist William I. Robinson

explains that polyarchy is a tactic in which democracy is

formally promoted by dominant social groups but limited by them

to narrow institutional boundaries to a system in which a small

sliver of society rules. When the tactic of polyarchy fails,

paramilitarism and other overt forms of coercion serve as a

backup option for dominant groups.

My book on this topic first

looks at the historical context of right-wing political violence

and the institutionalization of paramilitarism in Haiti.

However, the main part of the book, the case study, documents

the role of paramilitaries and their backers in the most recent

coup (in 2004) and what occurred afterward. I have sought to

provide what philosopher Peter Hallward found was still needed

regarding the coup, a “detailed reconstruction of the early

development of the FLRN insurgency.”

The second Aristide

administration was subjected to a relentless vilification

campaign in both the local and global press. It was often

depicted as being little different from the infamous

dictatorships that have plagued Haiti so often during its modern

history.

Hallward observes that the best

available data show that political violence during Aristide’s

time in office paled in comparison to the Duvalier dictatorship

and the unelected regimes installed after Aristide was twice

overthrown. The Duvalier dictatorships (1957–86) and the brief

dictatorships that immediately followed these carried out the

killings of somewhere between 30,000 and 50,000 people in total,

and after the coup of 1991, at least 4,000 — likely more

according to many sources — died under the subsequent three

years of dictatorship. After the 2004 coup, human rights

investigators carrying out a study of the greater Port-au-Prince

area found again that at least 4,000 Lavalas or similarly

politically oriented people had been killed in political

violence under the U.S./UN-backed post-coup regime. Even though

the study, based on a random sampling published in The Lancet,

was criticized by some, a number of other human rights studies

also reveal a high number of casualties resulting from the 2004

coup and the repression that followed.

By comparison, during

Aristide’s second tenure in office from 2001 to 2004 somewhere

between 10 and 30 persons were killed by members or supporters

of his government (in the context of clashes), and a larger

number of civilians and government supporters were killed by

elite-backed anti-government paramilitaries. There are no

reasonable grounds for concluding, despite the actions of a

small number of Aristide’s supporters and police, that the

policy of his government was to silence dissent through

violence. Thanks to the machinations of his foreign and domestic

enemies, Aristide, upon his 2001 inauguration, was already

saddled with a police force he would struggle to control. Though

individuals from both sides of the conflict are guilty of

violent acts, it is important to understand that the

preponderance of these acts (and often, the initiating acts)

originated from illegal armed organizations (working in league

with dominant groups) that opposed Haiti’s elected populist-left

government. The popular classes — and those organizing in their

interests — have been and continue to be the

primary targets of political violence.

The campaign against Fanmi

Lavalas was a broad and long-term destabilization project. The

campaign included mass media manipulation and an aid embargo on

the Haitian state that was backed by many of the powerful

embassies and larger NGOs active in the country. It involved key

U.S. allies — officials from Canada and France — often thought

of as being more autonomous, and distinct from U.S. elites. The campaign against Fanmi

Lavalas was a broad and long-term destabilization project. The

campaign included mass media manipulation and an aid embargo on

the Haitian state that was backed by many of the powerful

embassies and larger NGOs active in the country. It involved key

U.S. allies — officials from Canada and France — often thought

of as being more autonomous, and distinct from U.S. elites.

Writer and founder of the

organization TransAfrica, Randall Robinson recalls how

“no one could remember an occasion where the United States and

its allies had mounted a more comprehensive campaign to cripple

a small, poor country than they had in the case of democratic

Haiti.” But we must also note that through globalization many

state elites and capitalists from the U.S. (and from around the

world) have become more interested in promoting conditions for

global capital than national capital, becoming more and more

transnationally oriented in their outlook. Furthermore, numerous

studies by political economists and sociologists have documented

the objective integration through which so many dominant groups

have prospered in global capitalism (integrated to different

degrees through transnational circuits of production and

finance, or through various institutional processes). Local

dominant groups in Haiti have undergone important

transformations through capitalist globalization as well — yet

also face drastically different historic conditions than their

counterparts in more economically developed regions. Both

evolving and long-lasting differences in elite priorities are

revealed when examining the paramilitary campaign against

Aristide and Haiti’s popular movement. Early on, a hard-line

sector of Haiti’s bourgeoisie, old-school Duvalierists, a clique

within the Dominican Republic’s foreign ministry and army, and a

handful of disloyal power hungry individuals within Haiti’s

government provided the most direct support to the

paramilitaries. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) documents I

obtained show that the U.S. maintained channels of communication

with the paramilitaries and their backers for years, and also

suggest that France provided the paramilitaries financial

support. A wing of the transnationally oriented locally based

industrialists in Haiti also covertly backed the paramilitaries,

and many powerful foreign officials were content to ignore the

paramilitaries or, crucially, instigate an environment that

allowed the paramilitaries to thrive, and then, following the

2004 coup, sought to bring the paramilitaries under control.

Whereas these transnationally oriented supporters (or enablers)

of the paramilitaries have often hidden well their role in the

atrocities, some from the hard-line sectors of the country’s

bourgeoisie have been clumsier in covering their tracks.

The weakening of Haiti’s

police, in part through the machinations of the U.S. and the UN,

as well as through the corrupting influence of the narco-trade

and the local conflict over limited state resources, has allowed

the phenomenon of paramilitarism to reemerge. For example,

Washington pushed for the recycling of a small but influential

pro-U.S. group from the country’s disbanded brutal military

force into Haiti’s new police force during the latter half of

the 1990s, and then to a much larger degree in 2004–5 the

U.S. and the UN oversaw the recycling of 400 ex-army

paramilitaries into a revamped police force. By helping to

facilitate the continued influential role of such individuals,

dominant groups for many years have directly and indirectly

facilitated the phenomenon of paramilitarism — and the avoidance

of justice.

To understand the contemporary

development of paramilitarism in Haiti and the shifts it has

undertaken in recent years, we must look at its recent history

in four waves.

• The first wave: the Tonton

Macoutes were institutionalized under the Duvalier dynasty and

its successors throughout the late 1950s, ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s.

The brutal macoute power structure became pervasive in Haitian

society, leaching off the poor and displacing state resources.

Macoute stations (of different sizes) even in the same

neighborhood often had poor communication with one another and

instead communicated up through a hierarchal web of command.

Members also spied on one another through Duvalier's secret

police (the service detective), which was heavily

infiltrated into the macoutes to protect the regime from

internal plots (the secret police were sworn to secrecy about

their membership in the group).

Whereas repressive militias

existed in the past, the Macoute paramilitaries became a

permanent and institutionalized strata under the Duvalier

dynasty. Macoute paramilitaries also often served in Haiti's

army - forming a symbiotic relationship with the Fad’H (the

Armed Forces of Haiti). As political scientist Jean-Germain Gros

has explained, in some cases, “the sons of high-ranking Tontons

Macoutes, who were not qualified to enter the military academy,

or did not wish to submit to rigorous exercises, became officers

anyway, after taking crash courses at camp d’application.”

In an ethnographic study of

one Port-au-Prince neighborhood (Bel Air), Anthropologist Michel

Laguerre found that initially macoutes had been gathered from a

secret society, a literary association, and a group of civil

servants. Laguerre observed that: “The salaries of the Tontons

macoutes vary depending on there positions in the hierarchy and

their connection with officials in the government.” Some Tonton

Macoutes worked for city officials or were higher paid if they

worked directly for the national palace. Volunteers, without a

salary, benefitted from being able to wear a gun. Secret police

were remunerated behind closed doors, and according to one

individual interviewed by Laguerre, they were expected to use

their secret intelligence identification as a way to pressure

legislative cabinet members to regularly pay them off. With the

fall of Jean Claude Duvalier in 1986, the Tonton Macoute

paramilitary force was officially disbanded but many from their

ranks were carried over into new non-uniformed attachés.

Surface-level changes were made to deal with shifting political

dynamics occurring both within and outside the country.

• The

second wave: the attachés, as they were dubbed under

the regimes of Henri Namphy and Prosper Avril following the fall

of Jean-Claude Duvalier, were basically the continuation of the

Tonton Macoutes. They continued to work closely with the

country’s military but without the uniform and regalia the

Duvalier dynasty had bestowed upon them. Following the mass

mobilization against a January 1991 coup attempt launched by

attaché paramilitaries and then the inauguration of Haiti’s

first elected government on Feb. 7, 1991, the attachés went

briefly into the shadows as the military (at least publicly)

distanced itself from them. The new government also began to

disband the country’s rural enforcers (the section chiefs).

• The

third wave: following the coup d’état of September 1991, a

military regime seized power, and over time it increasingly

relied on paramilitaries, many formerly of the Tonton Macoutes

and attachés, to crush resistance. The main death squad, which

would come to be known as the FRAPH, coordinated with the CIA

station chief in Port-au-Prince while working closely with

Haiti’s military and some of the country’s wealthiest families.

It was used across the country to carry out brutal killings and

attacks, targeting activists from the popular movement. The

illegality of the coup, the extreme violence and corruption of

its enforcers, and the pro-democracy organizing of many Haitians

(and solidarity supporters) resulted in the de facto

regime being widely and accurately recognized as a pariah narco-state,

that ultimately in late 1994 the U.S. and UN intervened to

remove. Once democracy (with clipped wings) was restored in 1994

the paramilitaries went underground once again, with much of its

top leadership going into exile or hiding. Haiti’s democracy

instituted a truth-and-justice process, which, though facing

many difficulties, began for the first time to hold paramilitary

and military forces accountable for their crimes. The returned

democracy was also able to disband the country’s brutal military

and rural section chiefs. Yet the U.S. was successful in pushing

into Haiti’s new police force dozens of ex-FAd’H who remained in

close contact with the U.S. embassy. Haiti’s reconstituted

government also made the mistake of allowing in around 100 ex-FAd’H

that it believed had left their old ways (which turned out,

among some, not to be the case), although the government likely

had no choice but to give some concessions to the U.S. and seek

its own protection.

• The fourth wave: FLRN

paramilitaries emerged in late 2000, led by renegade police

officials who were from among the same ex-FAd’H, pushed into the

country’s new security force by the U.S. in the late 1990s. Over

the years these paramilitaries had become involved in narco-trafficking,

and by the turn of the century they had begun plotting with

their natural allies among the neo-Duvalierists, some sweatshop

owners, and some of the ex-FAd’H who remained in the government,

feigning loyalty. Over time, these relations appear to have

deepened and they worked with sectors of the country’s

bourgeoisie and even some leading transnationally oriented

capitalists in Haiti and the Haitian diaspora. This fourth wave

often presented itself as the “new army,” but once Aristide had

been driven from power in 2004 and the pro-Aristide slum

communities of Port-au-Prince were thoroughly repressed, the

FLRN leaders (increasingly divided among themselves) were

sidelined while at least 400 of their men were integrated (in a

process overseen by the United States, UN, and OAS) into a

post-coup police force.

Following the 2004 coup an

unelected and brutal interim government held office for over two

years, buttressed by a UN force, after which the popularly

elected administration of René Préval (a former prime minister

under Aristide’s first administration) took office. Though this

brought a partial reprieve from the extreme violence of the

interim government, Préval also governed widely in accord with

the policies of the transnational elite and with a heavy UN

presence in the country. Meanwhile, Fanmi Lavalas has been

denied participation in elections since the 2004 coup.

Since the 2010 earthquake,

taking advantage of the upheaval and social disarray it caused,

calls have heightened among the ex-military and right-wing

politicians within the country to reconstruct Haiti’s brutal

army. In March 2011, Michel Martelly, a popular musician

connected to Haiti’s bourgeoisie and longtime opponent of

Lavalas, was elected as president in a controversial vote. In

the presidential election, in which voters were allowed to

choose between two right-wing candidates, an extremely low

turnout occurred, with Martelly receiving the votes of only

16.7% of registered voters. Rather than focus on infrastructure

for the country’s poor, tragically harmed in the earthquake, or

turning attention to the country’s rural heartland (which is in

drastic need of attention), one of Martelly’s main goals has

been to rebuild Haiti’s army. With the FAd’H having been

disbanded for over 15 years (and a good deal of the ex-FAd’H’s

contemporary role in paramilitary violence never properly

exposed), it is an important historical juncture in Haiti.

The same month that Martelly

was elected, just a 40-minute drive from the center of

Port-au-Prince, I and two others visited a hilltop camp where

around 100 young self-proclaimed neo-Duvalierists and old-timers

from the FAd’H are active. I was told that in the late 2000s a

network of training camps had been developed around the country

by some of the ex-FAd’H that had also been in the FLRN. Under

the Duvalierist banner they train and vet new recruits for

private security companies while promoting calls for the return

of Haiti’s disbanded military.

Today in Haiti, neo-Duvalierist,

ex-army, and paramilitary networks remain active, although often

behind closed doors. Backed by a collection of wealthy elites

and hundreds of allies in Haiti’s police and government, and

buttressed by the shocking return of Jean-Claude Duvalier in

early 2011 and the poorly attended election of Michel Martelly

that same year, right-wing forces within the country are

emboldened, achieving their strongest position in decades.

Martelly’s government has declared that it will remake the army,

renaming it the Composante Militaire de la Force Publique,

by the end of his term. Whereas a top French official suggested

his government would finance the new force, the U.S. appears to

have ended its long-term arms embargo on the country’s

government. In July 2012, it was revealed that Brazil and

Ecuador (members of the UN force occupying Haiti) have offered

to help reform the army. There have been allegations that

Martelly’s brother-in-law was involved in a shady arms deal

purchasing thousands of automatic handguns supposedly meant for

the country’s security forces. The Martelly government’s key

constituency are top business leaders (as well as local sectors

of the bourgeoisie) and transnational policy elites whose

central goal is to stabilize the country for global capital. The

long-term strategy for development rests on the investment of

transnational corporations through cheap mining concessions and

textile industries through which they can leverage Haiti’s pool

of low-wage workers.

Opposition to these plans is

growing, however, and a campaign to halt the re-creation of the

army and hold Duvalier accountable for his crimes is bringing

together a cross section of Haiti’s civil society organizations

and grassroots popular movement. Groups such as the Boston-based

Institute for Democracy and Justice in Haiti (IJDH) and

Haiti’s Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI) have

spearheaded some such efforts. Others, such as the Center for

Constitutional Rights, Just Foreign Policy, and

SOA Watch have led human rights campaigns to hold U.S.

officials accountable for their policies overseas.

Following the rollback of

Haiti’s sovereignty with the 2004 coup d’état, the devastation

of the 2010 earthquake, and the heightened foreign political

intervention that occurred after the earthquake, it appears

unlikely that paramilitary criminals and their backers will face

justice any time soon. Even so, as Haitian political activist

Patrick Elie explains: “Today as Martelly talks about forming a

new army, this story must be told.” The more people understand

why criminals like Louis-Jodel Chamblain live in comfort, poised

to victimize more people if Haiti’s destitute majority dare to

raise their heads, the sooner the day will arrive when justice

and democracy prevail.

Citations for this article are available in the version

published in the September 2012 issue of Monthly Review Magazine

(Volume 64, Number 4). To order “Paramilitarism and the Assault

on Democracy in Haiti,”

visit the

Monthly Review website. |