|

A

“test” food voucher program in the Grande Anse département

(province) on Haiti’s southern peninsula promoted

consumption of imported rather than local food for almost 18,000

families, despite claims to the contrary.

In addition, the program – run by CARE with funding from the

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and supposedly

meant for victims of the Hurricane Tomas who had lost their

crops – did not begin until 11 months after the storm hit on

November 5, 2010.

The

program launched in October 2011, when food security was

improving. The “Food Security Outlook” report for that period –

July-December 2011 – noted that parts of Grande Anse were

“stressed,” but went on to say that “with the promise of more or

less satisfactory harvests in Grand’ Anse [sic], the upper

Artibonite, and the Southeast, food security conditions in these

areas are expected to improve between October and December.” The

report is one put out every three months the Famine Early

Warning Systems Network (FEWSNET), a U.S. government-run office

that predicts hunger and famine in conjunction with the Haitian

government and USAID.

Despite the improved forecast, CARE launched “Tikè Manje”

(“Food Voucher”) program, which later changed its name to “Kore

Lavni Nou” (“Supporting Your Future”). Funded by USAID, it

also had the endorsement of the government’s “Aba Grangou”

(“Down with Hunger”) leadership. After a timid beginning in

October 2011, the program got into full swing in the spring of

2012 – 16 months after Hurricane Tomas – a year-long

Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW) investigation determined.

HGW

asked the head of the government's Aba Grangou program

why CARE’s program was allowed to start so late.

“The project was meant to

help people affected by Hurricane Tomas,” Director Jean Robert

Brutus admitted. “By the time the project started, Grande Anse

had probably already started to recuperate. But since it had

already been set up, the U.S. government decided to implement

it.”

When

CARE was asked why Grande Anse was selected, rather than other

areas of the country – notably the Northwest, which habitually

suffers from extreme hunger – the program’s coordinator, Tamara

Shukakidze, said that CARE and another USAID contractor chose

Grande Anse to carry out “a test” after the hurricane caused

damage. In interviews with HGW, Brutus also used the word

“experiment.”

The

program “is simply a test in certain regions to see if we can

implement the program everywhere in the country,” explained

Shukakidze in a March 2013 interview, while the program was

still ongoing. At the time, CARE was hoping to be a contractor

for a future USAID-funded US$20 million “social security net”

program that will include food vouchers, CARE spokesman Pierre

Seneq told HGW.

People

get imported food, government gets a 10% cut

Some 12,000

families were chosen by CARE and community leaders for the

Kore Lavni Nou program, reportedly according to the

following criteria: families with no or little land, with two or

less animals, and/or with a child head-of-household or family

members who were disabled, extremely elderly, HIV positive, or

had other challenges.

Each

beneficiary received a monthly voucher worth 2,000 gourdes

(about $US46.51) that could be redeemed at specific merchants

for specific quantities of rice, vegetable oil, beans, imported

dried herring, corn meal, pasta, and bouillon cubes. HGW

research in several Grande Anse communes revealed that almost

all the products came from U.S. producers. (HGW was not able to

visit every single Kore Lavni Nou store.)

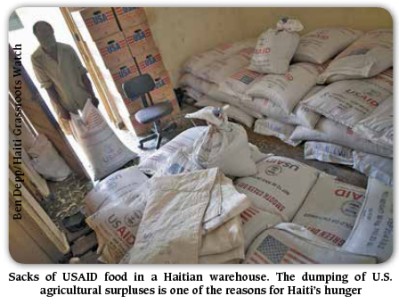

U.S.

law stipulates that almost all U.S. food aid must be U.S. grown

and processed food.

Like

many other food voucher and cash transfer programs in the

country, CARE signed a contract with the mobile telephone

company Digicel to assure the cash transfers. In addition to

paying Digicel for those services, the CARE program – and all

others – have to pay the Haitian government 10% on all “mobile

money transactions, including transfer to beneficiaries, vendor

payment, and cash out,” according to a 2013 USAID report.

After Hurricane Sandy caused damage to some Grande Anse farms in

October 2012, CARE extended the program with a “Phase 2,” adding

5,708 people to the roll, meaning that a total of 17,708

beneficiaries in Grande Anse received food coupons up through

the end of August 2013, according to CARE spokesman Seneq.

(Another 8,000 families in the Artibonite and Northwest

provinces were also added to the rolls for the period April

2013-end of October 2013.)

“A

total of over US$5 million will be directly distributed to

families facing food insecurity,” Seneq explained in a Jun. 18,

2013 email.

According to the USAID 2013 BEST report, CARE received US$7.4

million for the Grande Anse program.

Program

criticized by farmers, agronomists, others

Dejoie

Dadignac, coordinator of Rezo Pwodiktè ak Pwodiktris Agrikòl

Dam Mari (ROPADAM – Network of Dame Marie Agricultural

Producers), told HGW that the food voucher program represents “a

terrible threat” to Grande Anse farmers.

ROPADAM was one of seven organizations that signed a four-page

document denouncing the program in July 2012. The organizations

said they were shocked that their communities had been targeted

since, according to Haitian government documents, “not one of

the communes is classified as having ‘extreme hunger.’”

“As

everyone knows, Grande Anse is a breadbasket for vegetables and

fruit,” the organizations noted in their press release. “And we

see that this food aid program is taking place during our

harvest months, when a lot of vegetables and fruits go to

waste.”

More

shocking to Dadignac and the organizations was the almost

exclusive promotion of foreign food.

“At

every little store we visit, even ones that used to sell cement

or tin sheeting, we see a sign: ‘USAID,’” Dadignac told HGW in

September 2012. “In their radio advertising, they say they are

giving people plantains and breadfruit, but that’s not what we

see. We see rice, spaghetti, oil, while our products are left

out.”

“We

thought other departments would be coming to get our products to

take care of the hunger problem," Dadignac added. "We didn’t

think we’d end up seeing all this imported food here!”

A

CARE press release from 2012 claims that the “program supports

consumption of locally produced, traditionally appropriate,

products which are readily available in all communities.”

However, visits by HGW journalists to stores in two communes

during Phase 1 and two communes during Phase 2 did not find any

“locally produced” food aside from Haitian spaghetti, made with

imported wheat, and – in some, but not all locations – beans.

Asked if CARE used or was planning to use local food, spokesman

Pierre Seneq confirmed that mostly imported food was utilized in

the current programs, but that CARE was planning to source some

local food in future programs.

Jean

Robert Brutus, head of Aba Grangou, also admitted that

the Grande Anse programs mostly used foreign food.

“Everyone wanted [the program] to use local food, but the market

could not always provide it,” Brutus told HGW. He also said that

people cannot be forced to buy one thing over another.

“We

don’t force people who have vouchers to buy local products, but

we encourage them, and we encourage the distributors to make

local products available,” Brutus said. “We need to make an

effort to guarantee producers that their products will be

competitive with imported products and will be purchased, so

that they start to produce again.”

Brutus did not give details on how Haitian rice and other local

products would be able to compete with the highly subsidized

and/or cheaply produced foreign food.

In

the meantime, the agronomists in Grande Anse are as despondent

as Dadignac and other farmers. “It’s true, there are places in

Grande Anse where people are hungry,” agronomist Vériel Auguste

admitted.

Veriél is a member of a farmers cooperative. Like every farmer

and agronomist contacted by HGW, he bemoaned the use of foreign

food to help hungry people, since it undercuts local production,

makes people dependent, and, in the long run, contributes to

even more hunger.

“They call the program ‘Down with Hunger,’ but to me, it’s a

‘Long Live Hunger’ program,” he said.

Auguste also pointed out that the province has a lot of

cultivable land sitting empty, in part because cheap imported

food undercuts Haitian production, and in part because Haitian

farmers get no technical support from the government.

“A

long time ago, every week we would see four boats loaded with

food leave [Jérémie] every week, and there would still be food

left on the wharf!” he said. “Not any longer… but the land is

there. It can still be farmed.”

Agronomist Jean Wilda Fanor, who has worked in Grande Anse for

over 25 years, said much the same thing.

“Instead of an Aba Grangou program that promotes imported

food, the government should help develop the internal market so

producers can sell their products,” said Fanor, who currently

works for Entraide Protestante Suisse (Swiss Protestant

Aid).

Questioned by HGW in June 2013, the head of the government’s

Coordination Nationale de Securité Alimentaire agency (CNSA

or National Coordination for Food Security) also expressed

reserves about voucher programs that favor U.S. food.

“The

objective is to allow people to buy local food,” CNSA director

Pierre Gary Mathieu said. “If it is poorly targeted and people

buy imported rather than local food, then it penalizes local

production.”

Mathieu said he was aware of the “deviation” in Grande Anse,

which was a “very bad” experience, but added that thought it had

been corrected. However, as noted above, Phase 1 and 2 of CARE’s

program were identical.

Beneficiaries

and Vendors Happy

But

the program does have its cheerleaders. In publicity materials,

CARE lauds its program, which undoubtedly did feed families. And

of course, store owners were very pleased.

Silvain Julien said his store became part of the program in

March 2012 – 16 months after Hurricane Tomas.

“The

program is going very well, and people are asking me if it will

continue,” Julien said. His store was packed with bags of Tchako

rice from the U.S.-based cooperative Riceland, one of the

world’s largest rice exporters and the largest recipient of U.S.

government farm subsidies. According to Oxfam Senior Research

Marc Cohen, between 1995 and 2010, Riceland collected over

US$500 million from Washington.

Julien said Kore Lavni Nou “really helps people… not only

the beneficiaries, but also me, as a businessman. I used to sell

50 sacks [of rice], but now I sell 100 sacks. So business has

really improved.” Program beneficiaries were also pleased.

HGW

wanted to investigate whether all beneficiaries were indeed

victims of hurricanes Tomas or Sandy, and/or if they fit the

CARE criteria. Due to lack of time and human resources, a survey

with a representative sample was not possible.

However, HGW did note that Catholic Relief Services (CRS), which

also carried out a USAID-funded food voucher program in the

region, said there were signs of some corruption in a report

given at a September 2012 food voucher workshop sponsored by

USAID. A CRS PowerPoint obtained by HGW noted that “partisan

infiltration of beneficiary” lists was one of several

challenges.

Not

all Kore Lavni Nou beneficiaries were willing to speak

openly. But at one household in Chambellan – where at least two

voucher beneficiaries lived together – Marie Edith Dubrevil was

happy to talk. She represented herself as someone living in

“misery,” and told HGW that her region was “miserable.” She said

that she started getting coupons in June or July 2012, about 18

months after Hurricane Tomas, thanks to a church worker.

“Every now and then one of the supervisors would check to see if

my name got onto the list,” Dubrevil said. “Two months ago my

name came up... Now, thanks to the program, I get rice, and it’s

good rice… I wasn't able to eat that kind of thing because I am

poor, but now, thanks to CARE and USAID, I applaud them, because

my life has changed!”

Dubrevil and her aunt, 89-year-old Louima Leon, who is also a

beneficiary, said that before the program, they mainly ate

breadfruit, plantains, sweet potatoes, yam, and taro. “Now we

eat rice, beans, and cornmeal,” Leon said. [See Aid or Trade?

for more on diet changes]

Imported

supplants local

Since the

earthquake, the U.S. alone has provided US$22.5 million worth of

food vouchers to 179,000 people, according to the 2013 version

of the USAID-BEST Analysis, a report on USAID-funded food aid

produced every year.

While the CARE program focused on imported food, some programs

have utilized – at least in part – locally produced food. The

CRS food voucher program in Grande Anse allowed beneficiaries to

buy yams and potatoes, according to the agency’s report, made

public at the September 2012 workshop. (HGW was not able to look

into the CRS program.)

Another report, from Action Contre la Faim (ACF),

described a post-earthquake program for 15,000 families who

received “fresh food” vouchers. Merchants included street

vendors (most of whom are women) as well as shops.

Other food aid programs in Haiti use locally procured food. In

2012, the World Food Program (WFP) bought over 27% of its food

locally, according the BEST report. The WFP is also piloting the

purchase and distribution of local milk as part of the national

school meal program.

In

their written report on the workshop, Aba Grangou

representatives Frisnel Désir and Rédjino Mompremier expressed

their concerns, noting that the programs reviewed were all

short-term, “with no integration of regional production and with

no exit strategies. In other words, once the project is over,

the beneficiary will return to his or her original situation.”

Désir et Mompremier also called for more focus on local products

and on outreach to promote the use of local rather than imported

goods.

“People who are hungry clearly give imported products more

social value," they wrote. "The integration of local products

needs to be accompanied by other measures related to production

and to transportation all the way to the point of sale in the

future.”

Jean

Robert Brutus, director of Aba Grangou, told HGW that

everyone “learned lessons” from the Grande Anse program. Brutus

promised that the new food voucher program will promote local

food as much as possible, and will be “structured in a way that

encourages food producers in the region to produce food.”

“If

[a farmer] knows there is a guarantee that people will buy, he

will produce,” Brutus said.

So

far, details of new program have not been announced, but as of

this writing, it appears the current U.S. Farm Bill will be

extended again, meaning that most U.S. food aid programs will

need to use U.S. products.

Agronomists Auguste and Fanor both told HGW that Grande Anse

farmers will need more than a “guarantee” to improve their

output. Both said the government must intervene to deal with the

structural issues. But neither the government nor foreign

agencies have yet announced any major agricultural projects

aimed at increasing production in Grande Anse.

As

he walked around his demonstration plot, Auguste talked

excitedly about the potential of the peninsula. But he was also

very worried, because every year he sees more people leaving

their fields, nailing shut their fences, boarding up their

homes, and leaving for the capital.

“If

we don’t root out the structural causes and try to solve them,

we are going to become like Savane Desolée,” said Auguste,

referring to an arid region near Gonaïves whose name in English

means “Desolate Savannah.”

Fanor called on the government to build roads, help with

irrigation systems, and create seed banks. “The state has a

major role to play,” he told HGW.

In

the meantime, the farmers in the ROPADAM network continue to

farm and to promote their products, like “verichips” –

similar to potato chips but made with breadfruit (called “lanm

veritab” in Kreyòl).

“We

are the breadbasket for Haiti,” Dadignac told HGW. “We have a

government that has given up. We need agronomists, technicians,

who can help us produce more. We need agricultural stores where

we can find seeds and things. That’s what should be in the

government’s program.”

On

Sep. 27, USAID announced the launch of a new program, “Kore

Lavi” (“Support Life”). CARE will work with the Ministry of

Social Affairs to, among other actions, “reach approximately

250,000 households by providing food vouchers,” USAID said in

news release.

HGW asked CARE if the new program would be like the

“test” program in Grande Anse, with an emphasis on mostly

imported food. CARE promised a response via email by Oct. 5, but

then never followed through. |