|

Lack of financing for a ten-year

cholera eradication plan means that the disease will likely be

endemic to Haiti for years to come.

Cholera bacteria

are spread by contaminated food, water, and fecal matter. One of

the essential parts of the US$2.2 billion

National Plan for the

Elimination of Cholera in Haiti is the financing for sanitation

systems nationwide.

The majority of Haitians –

about eight million people – do not have access to a hygienic

sanitation system. They defecate in the open, in fields, in

ravines, and on riverbanks. The capital region produces over 900

tons of human excreta every day, according to the United Nations

Office for Project Services (UNOPS).

“Haiti is the only country in

the entire world whose sanitation coverage decreased in the last

decade,” said Dr. Rishi Rattan, a member of Physicians for

Haiti, an association of doctors and health professionals based

in Boston that works with Partners in Health and other Haitian

groups.

“Before the cholera outbreak or

the earthquake, diarrhea was the number one killer of children

under five and the second leading cause of all death in Haiti.

Given that cholera is a water-borne illness that relies upon

lack of access to clean water, it is highly likely that cholera

will become endemic in Haiti without full funding of Haiti's

cholera elimination plan by entities such as the United Nations

(UN),” Rattan told Haiti Grassroots Watch (HGW) in an email.

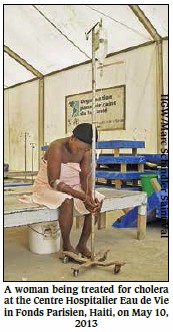

Cholera,

brought to Haiti in

October 2010 by soldiers from the United Nations Stabilization

Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), quickly spread throughout the

country. To date, over 600,000 people have been infected and at

least 8,160 have died, according to a government report dated

Jun. 30, 2013. Almost 3,000 people are infected each month.

The death rate is on the rise

in the countryside. Today, more than 4% of those infected die

due to the lack of cholera treatment centers. At the epidemic’s

peak, there were 285. Today, there are only 28. Once their

financing ran out, most humanitarian agencies abandoned the

country.

Worse, one of the two large

waste treatment facilities built following the earthquake

recently went out of service. [DINEPA just opened a third waste

treatment plant in Limonade on Jul. 24.]

The cholera-excrement connection

Written by the Pan-American Health

Organization (PAHO), the U.S. and Haitian governments, and

UNICEF, and published in November 2012, the cholera elimination

plan has as one of its main targets human excrement. The plan

sets as its objective that by 2022, “90% of the population has

access [to] and uses a functional sanitary facility” and that

“100% of drained excreta are treated before being discharged

into the natural environment.”

The sanitation budget will cost

more than US$467 million.

“According to our figures, less

than 30% of the population has access to what we might call

basic sanitation,” according to Edwige Petit, head of sanitation

for the government’s National Agency of Water and Sanitation (in

French, Direction nationale de l’eau potable et de

l’assainissement - DINEPA). “In neighboring countries, 92%

to 98% have basic sanitation.”

By DINEPA’s count, about one

half of households in the countryside, and 10% to 20% in the

cities, does not have access to a proper toilet or latrine. They

must use rivers, ravines, or almost any open space to take care of

their needs.

In Cité Soleil, a slum that is

part of the metropolitan area, some people are forced to use any

open patch of ground they can find.

“As far as latrines are

concerned, we ‘go’ wherever we can, do you understand?”

explained resident Wisly Bellevue, without a blink. “In other

words, we go in the wild, nearby.”

“When our children have to take

a poop, we put them on a little bowl,” he said. “We put a little

water in there. Once they are done, we throw it into an empty

lot.”

Big institutions with septic

systems are serviced by excreta trucks managed by the state,

UNICEF, or other agencies, or by private companies. In 2010 and

2011, for example, humanitarian agencies emptied the thousands

of portable toilets (“Johnny-on-the-spot” or “Porta Potty”) in

the refugee camps for the 1.3 million people made homeless by

the 2010 earthquake.

Those who cannot pay for the

luxury provided by the trucks have to hire a more economical

service: the men called “bayakou” in Haiti, who empty

latrines and septic systems by hand.

The bayakou work at

night. Most of them do not take their excreta to the DINEPA’s

new waste treatment centers, and instead dump their cargos in

rivers, canals, and ravines. The workers sometimes even dump

their human output on the ground nearby if the rising sun

catches them at work, because, at all costs, they try to avoid

being identified by the population.

Before the cholera epidemic,

even the trucks used to dump their “black water” (feces mixed

with urine) into the ravines that drain into the Caribbean Sea.

Since the cholera outbreak, the government and other authorities

have been trying to convince all the sanitation actors to empty

their loads at locations that do not put people’s health in

danger.

In late 2010, DINEPA and UNICEF

opened a giant temporary site in Truitier, north of the capital,

to receive all of the material collected from the refugee camp

portable toilets as well as from other locations. At the time, a

DINEPA representative told HGW that the giant pool of excreta

was “the start of at least some form of excreta management” for

Haiti.

Advances and Challenges

Since then, DINEPA and its partners have

made considerable advances in sanitation. With assistance from

the Spanish government, UNICEF and others, DINEPA build two

treatment centers for the capital region’s black water, and

hopes to build 22 others for a total budget of US$159 million.

To date however, only one has been started.

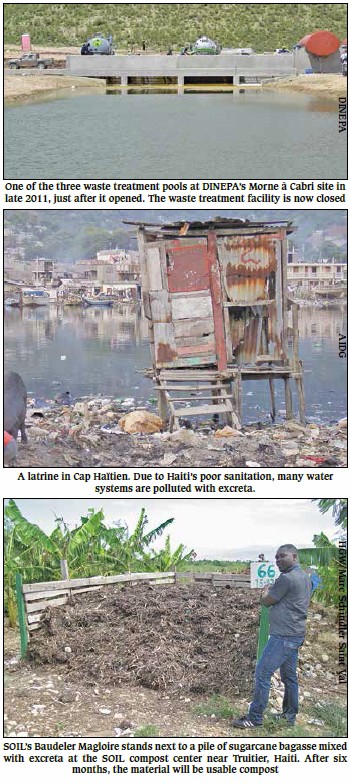

The impressive Morne à Cabri

waste treatment center, costing about US$2.5 million and

inaugurated in September 2011, “has the capacity to treat 500

cubic meters of excreta per day, which is the equivalent of what

500,000 produce,” according to DINEPA. But there is already a

problem.

Today, the center is closed

down. The excreta are not being delivered. The gates are locked.

Lack of financing is one reason. The fees paid by excreta

trucking companies don’t generate enough revenue.

Also, after the humanitarian

agencies stopped managing the refugee camps, because they said

they had no more financing, deliveries from the portable toilets

became problematic.

“We went from having latrine

matter being made up of 10% to 20% trash, to 70% to 80%,” Petit

explained. “The treatment center was not built to handle trash.

It was built to handle water and fecal matter. The pools

collapsed, blocked with trash.”

Even though it is struggling

financially, DINEPA is determined to get things working again.

“We are going to use government equipment. If we can get

US$40,000 or US$50,000 we will be able to clean it,” she said.

Of course, the other treatment

center is working, but one key challenge remains: how to

convince everyone to deliver his or her loads?

And even if the excreta are

delivered, financing will remain problematic. The excreta

trucking companies can pay, but the same is not guaranteed for

the bayakou. Perhaps this is why observers say the

journeymen continue to dump their loads wherever they can.

Frantz François is responsible

for sanitation and the gardens at a Cité Soleil community

center. “The bayakou do a bad job,” he said. “Right now,

at this moment, if you walk up and down the canal you will see

it is clean. But tomorrow, it will stink. They throw their

latrine loads wherever they want to.”

Another part of the national

cholera plan is national education campaigns aimed at combatting

“poor defecation and hygiene practices.” According to Petit,

many rural families don’t bother building latrines any longer;

they merely concentrate on building homes.

“Over the past 30 years, a

certain mentality has developed, where people know that it’s

quite possible somebody else [like a foreign agency] will give

them toilets,” Petit explained.

Rather than giving out free

toilets and latrines, DINEPA hopes to set up a US$120 million

fund that will allow families to borrow the money necessary to

do their own building.

An Alternative

DINEPA is not the only organization working

on the sanitation issue in Haiti. The U.S.-based

Sustainable

Organic Integrated Livelihoods (SOIL) treats and transforms

human excrement into compost that can be used as fertilizer.

SOIL supplies people and institutions who pay a small monthly

fee with special latrines. At least once a week, the

“Poopmobile” collects the excreta. So far, SOIL says there are

276 “Eco-san” toilets in operation around the country, serving

about 10,000 people.

SOIL’s compost installation is

located at Trutier, north of the capital, not far from one of

the two DINEPA waste treatment centers. Three people work there.

One empties the Poopmobile drums into the piles that become

usable compost after six months, while the others clean and

disinfect the drums so they can be reused.

“A lot of countries use this

system,” said Baudeler Magloire, project manager at SOIL. “Many

in West Africa. It is a new approach, a kind of ecological

sanitation.”

The approach is not completely

“new.” Human fecal matter has been used as fertilizer since the

ancient Chinese and Roman civilizations. The Aztec and Inca

peoples also used human excreta in their fields.

SOIL is not opposed to the

waste treatment “lakes” being used by DINEPA, but the objectives

are different, Magloire noted.

“Our mission is to allow for

the material to be recycled, transformed and then sent to places

in the country where it is needed,” he said. “People can buy it,

sell it, and use it in agriculture.”

Anti-cholera plan “in deep shit?”

While the Poopmobile collect fecal matter

from 24,000 latrines in a country of 10 million, three-quarters

of the population is still using non-hygienic practices and

systems.

The National Plan for the

Elimination of Cholera in Haiti requires US$2.2 billion, and a

plan for the neighboring Dominican Republic needs US$77 million

more. For the years 2013 and 2014 alone, the two countries are

seeking a total of US$521 million: US$443.7 for Haiti and US$33

for her neighbor.

The World Bank, PAHO, and

UNICEF recently promised US$29 million, and UN agencies have

offered another US$2.5 million. But, as of May 31 2013, the

pledges had not topped more than US$210 million, less than half

of what is needed.

“Investments in water and

sanitation are absolutely essential to eliminate cholera

transmission,” said PAHO Deputy Director Jon K. Andrus at a

Washington meeting where the grant was announced.

Andrus’ supervisor pleaded for

all donors to make commitments. “We must challenge governments

and partners to come up with the funds that are needed to get

the job done,” said PAHO Director Carissa F. Etienne. “The goal

is not just eliminating cholera. It is to ensure that every man,

woman, and child has access to safe water and sanitation. This

is basic to the dignity of every human being.”

Dr. Rattan of Physicians for

Haiti believes the UN should give the majority of the funding

needed, as soon as possible. “They have decreased the amount of

money they initially pledged and it has yet to actually be

disbursed,” Rattan wrote in a Jul. 17, 2013 email to HGW. “This

is crippling the Haitian government's ability to implement their

lifesaving cholera elimination plan.”

In Cité Soleil, Michelène

Milfort knows very well that there will be no plan implemented

any time soon. She lives in a tent with nine others. Her camp

has 38 deteriorating temporary shelters, tents, and shacks.

These earthquake victims only have three SOIL latrines to take

care of their needs. Before SOIL’s assistance, they used a

nearby empty lot.

John Abniel Poliné is a

neighbor. “Some people have no regular place to take care of

their needs,” he admitted. “Sometimes a person has to use a

little plastic bag, that he then throws into a canal. It is not

always the fault of the individual. You need to understand that

if the person had a place to go, he would not be forced to that

extreme.”

Poliné said he wonders about

the priorities of the Haitian government and of international

actors, especially MINUSTAH. “They just keep giving MINUSTAH

thousands of dollars, while the people of Cité Soleil live in

subhuman conditions,” he said.

MINUSTAH’s

2012-2013 budget is

US$638 million, over US$200 more than what is needed by the

Haiti and the Dominican Republic for the first two years of

their cholera elimination plans.

Haiti

Grassroots Watch

is a partnership of

AlterPresse,

the

Society of

the Animation of Social Communication (SAKS),

the Network of Women Community Radio Broadcasters (REFRAKA),

community radio stations from the Association of Haitian

Community Media and students from the Journalism Laboratory at

the State University of Haiti. |