|

Last week, for the first

time in its history, the Fanmi Lavalas (Lavalas Family) party

publicly cast out two of its leading members. It hadn’t done

this for other prominent members, such as Dany Toussaint in

2003, Leslie Voltaire in 2004, or Mario Dupuy in 2011, all of

whom, in one way or another, betrayed the party by allying with

right-wing political enemies. Last week, for the first

time in its history, the Fanmi Lavalas (Lavalas Family) party

publicly cast out two of its leading members. It hadn’t done

this for other prominent members, such as Dany Toussaint in

2003, Leslie Voltaire in 2004, or Mario Dupuy in 2011, all of

whom, in one way or another, betrayed the party by allying with

right-wing political enemies.

Instead, the two

parliamentarians singled out in a Dec. 2 press statement have

been spearheading the growing nationwide uprising demanding the

resignation of President Michel Martelly and Prime Minister

Laurent Lamothe.

“The Fanmi Lavalas Political

Organization protests with all its might against any public

declaration which comes from some people who present themselves

as Fanmi Lavalas members, Senator Moïse Jean-Charles and Deputy

Arnel Bélizaire,” read the note signed by FL coordinator Dr. Maryse Narcisse and other Executive Committee members including

former deputy Lionel Etienne, businessman Joel Edouard “Pasha”

Vorbe, and former right-wing politician Claude Roumain.

Finally, a great schism, which

has been growing in the party for months, burst into the open.

The leaders of two currents – one accommodating, the other

confrontational – stood glaring at each other.

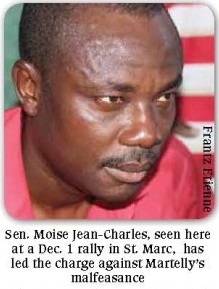

Sen. Moïse Jean-Charles

responded immediately to the note. The Fanmi Lavalas, he told

radio stations, has been taken over by a “macouto-bourgeois

group.” (The Tonton Macoutes were the Duvalier’s repressive

paramilitary force.)

“I have spoken with [former]

President [Jean-Bertrand] Aristide about it,” he said. “I told

him it is destroying the party. I told him that unless he made a

public declaration about it, I regret to say that the Fanmi

Lavalas will cease being a party which defends the masses’

demands. The bourgeoisie will simply take it over completely and

finish with it.”

Aristide’s response, according to Moïse: “I

am no longer involved in politics.”

A Little History

Haiti’s Lavalas movement was born in the

1980s during the struggle against the Duvalier dictatorship and

the neo-Duvalierist juntas which followed Jean-Claude “Baby Doc”

Duvalier’s flight from the country on Feb. 7, 1986. The goal of

the movement was a national democratic revolution to break the

chains of dictatorship and of foreign domination which had

hobbled Haiti for decades.

Meaning “flood” in Kreyòl,

Lavalas was an apt term for the movement which brought out

rivers and seas of humanity in demonstrations which often ended

with the chant “Yon sèl nou fèb, ansanm nou fò, ansanm,

ansanm, nou se Lavalas.” (Alone we are weak, together we are

strong, together, together, we are the flood.) It also connoted

a movement that was cleansing, penetrating, and unstoppable.

The movement, which had been

largely guided by relatively untouchable Catholic priests (most

of them liberation theologians) under the Duvalier regime,

coalesced around then Father Aristide in his Salesian parish of

St. Jean Bosco in the Port-au-Prince slum of La Saline.

The popular wave finally

carried Aristide to the presidency in a Dec. 16, 1990 election,

with Washington-backed former World Bank economist Marc Bazin as

his principal rival.

Aristide spent most of his

first presidency in exile after a 1991-1994 U.S.-backed coup

d’état, but then founded the Fanmi Lavalas Political

Organization (he doesn’t like to call it a party) in November

1996, winning the presidency again under its banner in 2000.

Washington, with the help of

Canada and France, again helped remove Aristide through a coup

on Feb. 29, 2004, driving him ultimately into exile in South

Africa, from which he didn’t return until Mar. 18, 2011, two

days before a presidential election drew a record low 24% voter

participation in large part because the Fanmi Lavalas was

excluded. On his arrival, Aristide called for “inclusive

elections.” Former ribald konpa singer Michel Martelly

won the Mar. 20, 2011 polling, although Haiti’s Electoral

Council never ratified the vote, hence rendering it illegal.

Martelly Government Corruption

Although at first grudgingly tolerated by

the Haitian masses (“Let’s see what they can do” was the phrase

often heard at the time), Martelly’s regime over the past two

and a half years has become deeply unpopular after carrying out

a long list of illegal and provocative acts including: the

arrest of peaceful protesters, of Arnel Bélizaire (an

immunity-protected sitting deputy), and of plaintiffs in a suit

against government corruption; the unilateral taxing of

international money transfers and phone calls, the millions of

dollars in proceeds from which go into an opaque

presidential-controlled account; the formation of several

private right-wing militias; the release or protection of known

criminals who are close to the President; and the ramming

through of Constitutional changes and a bizarre, unlawful

electoral council.

But the most salient feature of

the regime is its unprecedented and unabashed corruption.

Highlights include: a $20,000 per diem for the President on his

frequent trips abroad, on which he takes his family and large

entourages who are given equally obscene per diems; 12

documented kick-back payments totaling $2.6 million from

Dominican Sen. Felix Bautista for post-earthquake construction

contracts; and the disappearance into thin air of another $100

million in post-earthquake international funds for rebuilding of

a devastated Port-au-Prince neighborhood, which still lies in

shambles.

The corruption centerpiece,

however, is the regime’s siphoning off of about $1 billion from a

fund filled by revenues from Venezuela’s provision of all

Haiti’s petroleum needs. Under the 2007 PetroCaribe agreement,

Haiti only has to pay from 40% to 70% of its oil bill up-front,

with the remainder going into a fund which has to be repaid over

the next 25 years at 1% interest. The Martelly government

“borrows” from that fund for an assortment of supposed poverty

alleviation programs with catchy names like Ede Pèp (Help

the People), Ti Manman Cheri (Dear Little Mother), Aba

Grangou (Down with Hunger), and Banm Limyè, Banm Lavi

(Give Me Light, Give Me Life). But the true beneficiaries, it

turns out, are Martelly cronies and family members, like his

wife Sofia and son Olivier, who pull down millions in salaries

for supposedly running these programs.

Enter Moïse

Leading the charge to denounce this

corruption, repression, and lawlessness has been Senator Moïse

Jean-Charles, who represents the North Department after having

served as the Lavalas mayor of Milot, the town beneath Henri

Christophe’s famed mountain-top Citadelle, a nationalist symbol.

Starting in late 2011, he began to take to Haiti’s airwaves

weekly to

bare the details of Martelly’s

malfeasance. Government officials and fellow

lawmakers would bring him juicy details of the Martelly regime’s

dirty dealings, and in Senate hearings, he would often grill squirming

government ministers on the patent disappearance of funds from

this or that project.

Moïse has also led the fight to

end the almost 10-year-old Washington-backed foreign military

occupation known as the UN Mission to Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH).

He stewarded two unanimous Senate resolutions setting deadlines

for withdrawal of the UN’s 9,000 troops (now set for May 28,

2014) and has traveled to Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay to

lobby government officials and lawmakers, winning a 90-day

pull-out promise from the latter country’s president last month.

With an almost photographic

memory, a knack for numbers, and a charismatic presence even

over the radio, Moïse quickly became the people’s champion.

Deputy Arnel Bélizaire, who

comes from and represents some of the capital’s most rebellious

neighborhoods in Delmas, was also embraced by Haiti’s popular

organizations, not only because of his arrest, but because of

the progressive programming on his radio station RCH 2000 and

his single-handed disruption of several unpopular votes in

Haiti’s largely-bought-off House of Deputies.

Meanwhile, the Executive

Committee of the Fanmi Lavalas (FL) has remained completely mute

on the crimes and excesses of the Martelly government and

the continuing UN military occupation. “Inclusive elections”

became its one and only call.

Already the popular

organizations which make up FL’s base were not too enamored with

Dr. Maryse Narcisse, who had been Aristide’s and the party’s

spokesperson since 2007. (In May, at his first press conference

since returning to Haiti, Aristide announced that Narcisse would

be the FL’s new coordinator, making her likely the party’s next

presidential candidate.)

Dr. Narcisse, who was born into

Haiti’s bourgeoisie, had never militated in any popular

organization and was considered something of a outsider who had

been parachuted into her position of influence.

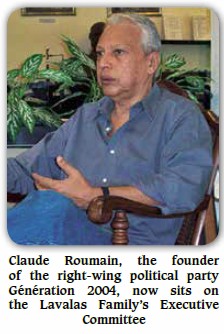

Furthermore, the FL’s Executive

Committee now included Claude Roumain, the former head of

Generation 2004, a right-wing party which had been allied in

1990 with Marc Bazin’s Movement for the Installation of

Democracy in Haiti (MIDH) in an electoral front known as the

National Alliance for Democracy and Progress (ANDP). When Bazin

became de facto Prime Minister in 1992 during the first

coup against Aristide, Roumain acted as his Secretary of State

for Youth and Sports. According to the pro-Lavalas website

ToutHaiti.com, Roumain was also a supporter of the 2004 coup

against Aristide.

Despite popular grumbling about

Narcisse, Roumain, and others on the Executive Committee and the

growing gulf between the leadership and its base, the party kept

up a brave face of unity.

Two Currents Emerge

As Moïse continued his crusade,

increasingly calls emerged from the Haitian masses through radio

programs and demonstrations for Martelly’s resignation.

The tipping point came in July.

In early 2013, a Haitian citizen, Enold Floréstal (now jailed),

initiated a lawsuit against Martelly’s wife and son for

corruption. The case was given to Investigating Judge Jean Serge

Joseph, who issued subpoenas for Lamothe and other high

government officials. Martelly was reportedly enraged by the

inquiry, and on Jul. 11, he ordered the judge to back off,

literally spitting curse-filled threats in his face. The secret

meeting, with Lamothe and Justice Minister Jean Renel Sanon also

in attendance, was held at the law offices of Martelly’s legal

counselor Garry Lissade, who had been the lawyer for 1991 coup

leader General Raoul Cédras at the 1993 Governor’s Island

negotiations in New York.

On Jul. 13, two days after

being chewed out by Martelly, the completely panicked Judge

Joseph died from a cerebral hemorrhage brought on either by

stress or poison. Both Martelly and Lamothe publicly and

repeatedly denied having ever met the judge or attended the

meeting at Lissade’s office. But both the Senate and House of

Deputies have

issued reports based on the

testimony of dozens of witnesses – co-workers, judges, security

agents, family members, etc. – detailing the meeting and the

regime’s threats, lies, and attempted cover-up.

Both reports, as well as a

resolution by 13 deputies and the entire Senate, called for

Martelly’s impeachment, and the firing of Lamothe and Justice

Minister Sanon. But any impeachment proceeding must be brought

by the House of Deputies, where the majority block – the

Parliamentarians for Stability and Progress (PSP) – is firmly in

Martelly’s pocket.

With the legal road blocked,

the masses have increasingly resorted to the streets to demand

Martelly’s resignation. At about the same time, Narcisse issued

a statement saying the FL was opposed to Martelly stepping down

before the end of his term. She called only for elections, and

during the summer, the party began to organize electoral

campaign rallies in towns around Haiti.

But tensions have grown when –

in towns like Mirebalais, Miragoâne, Port-de-Paix, St. Marc, and Aux Cayes

– Moïse has arrived and converted FL electoral rallies into

anti-Martelly mobilizations. His message was simple: no free,

fair, and sovereign elections are possible under Martelly and

foreign military occupation. The rallies usually end with the

crowds carrying Moïse away on their shoulders to shouts of

“Martelly out, MINUSTAH out,” leaving Narcisse and the Executive

Committee fuming.

The Last Straw

Huge anti-Martelly demonstrations were held

on Sep. 30, Oct. 17, and Nov. 7 in Port-au-Prince, Cap Haïtien,

and other provincial cities. At another giant anti-Martelly

demonstration on Nov. 18, Moïse announced a march on the U.S.

Embassy in the Port-au-Prince suburb of Tabarre for Nov. 29, the

anniversary of a 1987 election massacre.

Rumors spread on radios and

websites (but were never confirmed) that U.S. Ambassador Pamela

White had met with Aristide’s wife, Mildred, after the march was

announced.

Two days later, the FL

announced that on Nov. 29 that it would hold a march to lay

flowers at the Argentine School at Ruelle Vaillant, the site of

the worst bloodshed 26 years ago.

The two currents now stood

face-to-face. Whose call would the Lavalas popular organizations

and the masses heed?

On the morning of Nov. 29,

Venel Remarais of the FL-aligned Radio Solidarité and Haitian

Press Agency (AHP) issued a bitter editorial against the march

on the embassy, in which he accused Moïse (without naming him)

of being a “Rambo,” an “individual, a revolutionary with great

political ambition,” of suffering from “vertigo from having a

swollen head,” and of thinking “he is the center of everything.”

“It is in respecting the rules

of the game that all victory is possible, not in rebellion,

hot-headedness, and charging ahead,” Remarais said.

He even suggested that a

“rarely seen personality,” an apparent reference to Aristide,

might be at the Ruelle Vaillant

flower-laying.

In the end, only a few hundred

people turned out to the Executive Committee’s Ruelle Vaillant

demonstration, while many thousands marched on the embassy,

although Haitian police dispersed the demonstration with teargas

and gunshots in the air before demonstrators reached the

building. The people’s inclinations and allegiance were

clear.

The coup de grace came two days

later during a Dec. 1 FL rally in St. Marc. Moïse again

electrified the event, with a passionate speech calling on the

people to beware of “traitors who are in the National Palace,

who are in this crowd, who are everywhere... Veye yo, veye yo,

veye yo!” Keep an eye on them!

“We demonstrated and marched on

the National Palace [Sep. 30 & Oct. 17]. Then we went to see

Pétion in Pétionville [Nov. 7]. Then we decided to go visit

Uncle Sam, but a few of them didn’t want to come with us... For

their personal interests, they’re afraid of Uncle Sam. But since

we are the children of [Haiti’s independence war leader and

founding father Jean-Jacques] Dessalines, we are not afraid to

look [the Americans] in the eye. [The Americans] bombarded us

with their gunshots. But we’re going back there.”

Warned by other FL officials at

the St. Marc event about Moïse’s fiery speech, Narcisse and

other Executive Committee members decided not to even show up.

The next day they issued their note.

What Lies Ahead?

In his spirited response to the FL

Executive Committee, Moïse removed the gloves he’s worn for

months.

“Maryse Narcisse used to work

for USAID alongside Pamela White and Sofia Martelly,” Moïse told

Haïti Liberté. “It is no wonder she today adopts the

positions she does.”

“I have been twice elected

mayor of Milot under the Fanmi Lavalas banner,” he continued.

“People like Claude Roumain cannot put me out of a party which

they have never even belonged to.”

Meanwhile, Aristide has

maintained his silence, making no public statements in support

of either side.

The FL leadership appears ready to go into

municipal and partial Senate elections at some point in early 2014, as the

Martelly regime’s Electoral Council has promised and as the U.S.

would like. Washington has already kicked in $10 million and the

European Union 5 million euros for the election. The Deputies,

in extraordinary session, finally passed the long delayed

Electoral Law on Nov. 28. On Dec. 10, the National Palace

announced that the new law had been sent for promulgation in the

official journal, Le Moniteur.

Will the prospect of elections

break the mobilization to uproot Martelly? Will the FL

leadership enter into an agreement with the Martelly regime to

take part in elections, from which the party has been excluded

for the past decade?

“Anybody thinking of going into

Haitian elections with Martelly should look at the

blatant electoral fraud

just committed in Honduras,” said Henriot Dorcent, a leader of

the Dessalines Coordination (KOD), a political grouping which

organized a Sep. 29 Popular Forum

to come up with a formula for a post-Martelly provisional

government that could hold elections. The solution about 150

popular organization delegates came up with was very similar to

the transitional government which held Haiti’s highly successful

1990 elections which brought Aristide to power for the first

time.

“Martelly cannot even hold an honest Carnaval,”

quipped Moïse, referring to how the president illegitimately

intervened in the picking of bands for Haiti’s yearly

celebration. “How can he be expected to organize a fair

election, especially after all that we have seen he is capable

of doing?” |