|

January 12, 2014 marks the

fourth anniversary of the massive quake in Haiti that left over

200,000 people dead and several million people homeless. The

response from rich countries was overwhelming—over $9 billion

was disbursed towards relief and reconstruction efforts ($3

billion from the United States, an estimated $3 billion in

private contributions, and another $3 billion from foreign

governments).

Four years later, the

earthquake in Haiti is mostly forgotten. The UN Office of the

Special Envoy for Haiti and charitable organizations such as the

Bush Clinton Haiti Fund have quietly closed their doors. Many

non-governmental organizations in Port-au-Prince have scaled

down their operations. Other disasters, such as Typhoon Haiyan,

dominate the news.

I can think of at least two

reasons why we should still care about what happened in Haiti.

The first reason is that despite the fact that a sum of money

almost equivalent to the GDP of Haiti was disbursed to

non-governmental organizations, for-profit contractors and other

agencies, most Haitians live without a reliable supply of

electricity, clean water, or paved roads. Several thousand

Haitians still live in (now tattered) tents provided as part of

the relief effort.

The second reason is that

understanding what happened in Haiti is critical if we want to

do a better job with relief and reconstruction efforts in the

aftermath of future natural disasters. Despite commitments made

by rich country governments and non-governmental organizations

towards greater aid transparency, and the availability of

easy-to-use tools such as the International Aid Transparency

Initiative (IATI) and UN OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service, it

is impossible to trace how the money was spent, how many

Haitians were served, and what kinds of projects succeeded or

failed.

The United States is the single

largest donor to Haiti. To be fair, USAID has released some data

from its files. And it has committed to reporting its data in

the standard IATI format. The USAID Transactions database does

have data on obligations and disbursements for FY2013

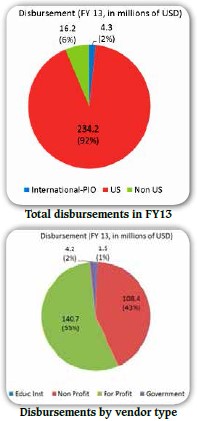

(disbursements are shown in Figure 1). We know that 92% of funds

disbursed in FY2013 went to organizations that are based in the

US. Figure 2 shows that the majority of disbursements in FY13

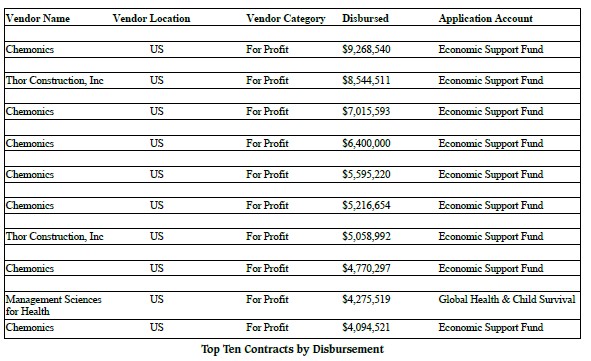

were to for-profit companies; Figure 3 shows that Chemonics — a

for-profit provider — received 7 of the largest 10 contracts,

totaling $42 million. Separately, USAID has also released data

on local procurement through its USAID Forward initiative.

This is where the trail goes cold. Typically,

USAID’s primary contractors use subcontractors to implement

their projects; these are the actors who actually get the work

done in Haiti (and elsewhere). USAID’s primary contractors are

obligated to report data on the activities of their

subcontractors, which in turn should be made public in

accordance with the Federal Funding Accountability and

Transparency Act of 2010. But this information is nowhere to be

found.

There are other challenges. The labels used

to categorize USAID’s spending (for example “ Economic Growth”,

“Governing Justly and Democratically”) are not easy to

interpret. They do not correspond to the categories and sectors

used in USAID’s Foreign Assistance Dashboard, but rather to

USAID’s strategic goals.

Also, almost half of the

transactions data have missing values for the Data Universal

Numbering System (DUNS), which serves as a unique identifier for

vendors and transactions. Data on local procurement contracts in

Haiti, released through the USAID Forward initiative also lack

this information, making them impossible to compare with the

transactions data, despite being released by the same

organization. In addition to the missing DUNS data, 35% of

vendor names (corresponding to $16 million in disbursements) and

34% of award numbers ($18.4 million) are not reported.

Members of the United States

Congress have recognized that data transparency is necessary for

continued progress in Haiti; as well as for effective foreign

assistance writ large. Led by Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA), the House

recently passed HR 3509, Assessing Progress in Haiti Act of

2013. The bill requires a GAO report reviewing US assistance

efforts, which is an important first step.

It is an outrage that four

years after the quake in Haiti, we have almost no idea of where

all the money has gone. Without data on procurement,

expenditures, and outcomes, we cannot know what works and what

does not. USAID’s subcontractors routinely provide data on their

activities to the prime contractors — these data can and should

be made public by USAID. The International Aid Transparency

Initiative is the ideal platform to report data in real time,

but simply publishing to USAID’s existing data portals is a

relatively simple process that USAID should move forward with

this year.

First published by the Center for Global Development |