|

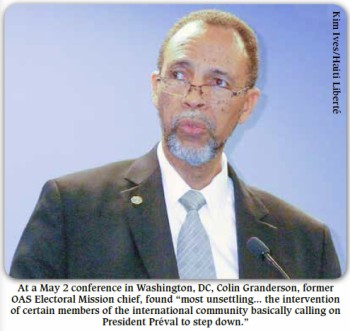

Speaking in early May at

the

“Who ‘Owns’ Haiti?”

symposium at George Washington’s Elliot School

of International Affairs, Colin Granderson, the

head of the CARICOM-OAS Electoral Mission in

Haiti in 2010-2011 confirmed previous accounts

that the international community tried to force

then-president René Préval from power on

election day.

That the

international community had “offered” President

Préval a plane out of the country during Haiti’s

chaotic first-round election in November 2010

was first

revealed by Ricardo

Seitenfus, the former OAS Special

Representative to Haiti. Seitenfus subsequently

lost his position with the OAS, but Préval

himself soon confirmed the story,

telling author Amy

Wilentz: “‘At around noon, they

called me,’ he said in an interview at the

palace recently. ‘It’s no longer an election,’

they told me. ‘It’s a political problem. Do you

want a plane to leave?’ I don’t know how they

were going to explain my departure, but I got

rid of that problem for them by refusing to go.

I want to serve out my mandate and give the

presidency over to an elected president.”

Despite

accounts of the story from three different

high-level sources who were there, the story has

gained little international traction in the

media.

In filmmaker

Raoul Peck’s documentary “Fatal Assistance,”

Préval

revealed

that it was the head of the UN mission in Haiti

at the time, Edmond Mulet, who made the threat.

(Seitenfus recently offered his recollection of

discussions with Mulet and other high-level

officials that day in an

exclusive interview

with CEPR and freelance Georgianne Nienaber.)

For his part, Mulet categorically denied the

event,

telling Catherine

Porter of the Toronto Star: “I never

said that, he never answered that,” Mulet told

the Star when asked about Préval’s allegation.

“I was worried if he didn’t stop the fraud and

rioting, a revolution would force him to leave.

I didn’t have the capability, the power or the

interest of putting him on a plane.”

The election,

plagued by record-low turnout, problems with

voter registration and

massive irregularities,

was in doubt on election day when, around noon,

12 of 18 presidential candidates held a press

conference calling for the election to be

cancelled. Speaking at last month’s symposium,

Granderson discussed what happened next:

“The

international community intervened, working with

representatives of the private sector, and

managed to get two of the candidates to reverse

themselves, to renege on their commitment, and

this rescued the electoral process. But what I

think was most unsettling, was that following

this attempt to have these elections cancelled,

was the intervention of certain members of the

international community basically calling on

President Préval to step down.”

This wouldn’t

be the end of the international community’s

intervention in the electoral process. After

first-round results were announced showing

Mirlande Manigat and Préval’s successor Jude

Célestin moving on to the second round, a team

from the OAS was brought in to analyze the

results. Despite having

no statistical evidence,

and instead of cancelling the elections, the OAS

team overturned the first round results,

replacing Célestin in the second round with

Michel Martelly. Seitenfus has described in

detail how this intervention was carried out, in

his

recent interview

with CEPR and in his forthcoming book,

International Crossroads and Failures in Haiti.

|