|

A large-scale tourism project planned for the

Haitian island of Île-à-Vache targets “the

well-heeled tourist from traditional

markets…creating a place of exquisite peace and

well-being,” as described in the government of

Haiti’s

executive plan.

The project aims to attract four character

types: “the Explorers, the Lovers, the

Rejuvenators and the Homecomers.” The

corporations behind the project intend to build

1,500 hotels and bungalows along the island’s

beaches, an international airport, a golf

course, island farms, and tourist “villages”

with cafes, shops, and night clubs.

The government

touts the project as “community hand-in-hand”,

with “equitable distribution of benefits for

all.” It says the tourism will be “mothering

[to] nature” and is for the “general good.”

The community

sees it very differently. A grassroots group,

Collective for Île-à-Vache (KOPI) [Konbit

Oganizasyon Peyizan Ilavach], was formed in

December 2013 and immediately began organizing

multiple peaceful protests, strengthening the

voices of the local community, and connecting

with allies.

Community

members have been mobilizing because they

understand the multiple challenges ahead if the

project continues as planned. Problems will

likely include displacement of people from their

land, forced migration to the overcrowded

capital in search of work, loss of food

production in a hungry nation, further economic

impoverishment, and environmental and cultural

degradation.

The

administration has been making empty promises

and telling lies to the inhabitants of the

island, while systematically violating their

rights and using violence to repress and

intimidate those who have been peacefully

protesting.

Special police

forces, such as the Motorized Intervention

Brigade (BIM) and the Intervention and Order

Maintenance Corps (CIMO), have a permanent

presence on the island now. Preceding the

inception of the tourism project, there were

only three police officers. In the last two

weeks, a SWAT team has been introduced to the

island. [The team was described in one account

as more than 50 special police forces dressed in

black with masks.]

The

vice-president of KOPI, Police officer Jean

Mathelnus Lamy, was arrested on Feb. 21.

He was moved to the National Penitentiary

in Port-au-Prince on Feb. 25, where he remains

without official charges.

The “peace and

well-being” envisioned for the tourists have not

extended to the local population. On the

contrary, there is a sense of fear around what

is impending. It began when the government

issued an official decree on May 10, 2013 making

all of the offshore islands zones of tourism

development and public utility. The proposed

plans for the project were created by three

Canadian companies: Resonance, 360 VOX, and

IBI/DAA. They have little understanding or

attachment to community needs.

Since then, the

situation has gotten much worse. In August 2013,

groundbreaking for the international airport

flattened an old-growth forest, which was

considered community land. Truxton began

dredging a pristine bay known as Madam Bernard

without an assessment of the environmental

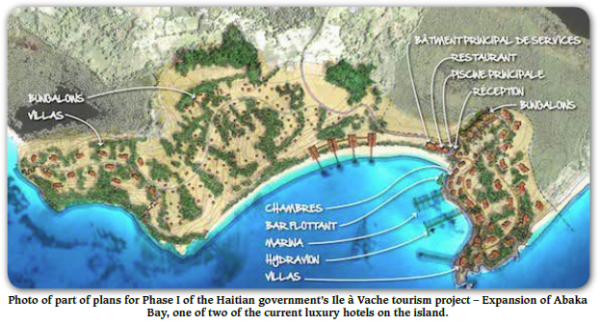

impact on marine ecosystems. Abaka Bay, which is

one of the two luxury hotels on the island,

illuminated the issue of waste management when a

recent human rights delegation spotted the

resort’s current method of waste disposal behind

the resort. Garbage – cans, plastic bags,

cardboard boxes, food – were just strewn

willy-nilly in the bushes (see photo). The

expansion of Abaka Bay is part of phase I of the

project.

Construction on

a new road began in late 2013, without any

notice, damaging a number of homes and taking

out up to 18 coconut trees, which were a

critical part of one household’s livelihood. No

compensation was offered for the losses, though

that is required by the Haitian Constitution.

The company working on the road and airport is

the Dominican Company Ingeneria Estrella.

We spoke to one elderly woman whose home is near

the airport and has been marked for demolition,

as she understands, by the Office of Land

Registry (DGI). She stated about the Estrella

workers, “They come in and out of my yard

without notice and they enter without even a

greeting.”

The collective

KOPI has been organizing with other grassroots

and human right organizations from

Port-au-Prince. The group’s demands are (1)

transparency and communication about the

project, (2) retraction of the May 10, 2013

decree stating that the island is for tourism

development and public utility, and (3) release

of KOPI’s vice-president, Jean Mathelnus Lamy,

who remains in the National Penitentiary, and

(4) removal of the special police forces from

the island. KOPI consists of 11 steering members

and seven additional members in each of the 26

localities on the island.

Largely, the

island community is not opposed to tourism. They

are in favor of development which is respectful

of their needs, which does not exploit nor

threaten to take away their land; a project in

which their participation is central and

integral. However, they strongly oppose the

current iteration of the project which is

systematically violating their rights.

Last week,

Prime Minister Lamothe visited the island again

with a government delegation consisting of the

Minister of Justice and a delegate from the

Ministry of the Promotion of the Peasantry.

Multiple communications were issued during this

visit from the

Ministry of

Communication and

Martelly-friendly outlets, including

Haiti Libre, show what appears to be the prime

minister talking to a supportive population

about social programs and distributing food.

The untold

story in these communications by Prime Minister

Lamothe and Minister of Tourism Stephanie Balmir

Villedrouin is that the population was told each

household would receive 10,000 gourdes, or about

US$220, during the visit to help boost

microenterprise. When the delegation arrived, no

money was distributed, but rather sacks of rice

and crackers. Close inspection of the picture of

Lamothe speaking, which was circulated by Haiti

Libre and the Minister of Communications, shows

the audience actually standing in a line for

this hand out.

While the

population protested the visit with burning

tires and blockades, there were few people

taking to the streets because of the SWAT

presence which accompanied the delegation.

Warrants were issued for the arrest of KOPI

leaders. Many of them have left their homes and

gone into hiding, unable to continue with their

daily livelihood activities.

Villedrouin continues to say publicly the

tourism development project is for the

community, while the lies, intimidation, and

repression continue. The population’s claims

were verified in a report issued on Apr. 2, 2014

[by eight Haitian human rights groups which

visited the area] to investigate the tensions.

Similar recent

foreign investment schemes in Haiti, like new

free trade zones, have not brought the

much-touted government line of better incomes.

Residents of Île-à-Vache are concerned that they

will have no power to enforce even the daily

minimum wage of $5.11, as has happened with new

sweatshops. Further, Haiti’s tourism industry -

when it was flourishing in the 80s – created a

collision of wealth and extreme poverty which

promoted other informal economies, such as the

sex industry which was illuminated in the film

“Heading South.”

Under the

platform “Haiti is Open for Business”, the

Martelly/Lamothe Administration continues to

entice foreign investments with images of

stability and security, building of

infrastructure financed by PetroCaribe, and

incentive policies such as a 15-year exemption

from local taxes and duties exonerations on the

import of equipment, goods and materials.

Tourism is one

of the development pillars of the government in

reconstruction/rebuilding following the 2010

earthquake. Tourism is supported by the Bill

Clinton, UN Special Envoy to Haiti, who speaks

of “Building Back Better.” The other economic

pillars include mining, free-trade zones, and

monocropping for export, all of which are direct

affronts to the livelihoods of the rural

peasantry and to food and land sovereignty.

The situation

on Île-à-Vache is indicative of all the woes of

Caribbean tourism and the model for what is to

occur across Haiti. The government continues on

its path to implement development to shape what

it is calling “an emerging country by 2030.” In

reality, these modes of development are further

displacing and increasing urban migration;

detaching and alienating the peasantry from the

land with few alternatives.

Villedrouin

does not speak about displacements, but rather

“relocation,” when addressing residents of the

island, while reporting to Reuters that only 5%

of the population will be displaced. Lamothe

promises there will be no displacements.

Simultaneously,

there are still displacement camps in

Port-au-Prince more than four years after the

quake. There is no relocation plan for the

residents of these camps, and in some areas of

Port-au-Prince there is still rubble remaining.

If this is the precedent for what happens to

those who are displaced in Haiti, then the

inhabitants of Île-à-Vache should be concerned

about their futures.

Will many

farmers and fishers from the island end up in

Haiti’s shantytowns, as have hundreds of

thousands of displaced farmers before them?

Those who were living in hillside shantytowns

had the highest mortality rate from the

earthquake. Île-à-Vache’s population continues

to be unsettled, uncertain of its future.

And so the

Île-à-Vache community sings in protest:

Caller:

Nou gen kasav (We

have cassava)

Nou gen kafe (We

have coffee).

Group Response:

Nou pa bezwen pwoje sa (We

do not need this project).

The following is adapted from a presentation by

Jessica Hsu of Other Worlds and Jean Claudy

Aristil of Radio VKM Les Cayes at the Executive

Symposium for Innovators in Coastal Tourism

conference in St. Georges, Grenada held from

July 8-11, 2014.

|