|

Five

years ago this month, the first cases of cholera in more

than a century started to multiply in Haiti’s Artibonite

Valley. Today, some 9,000 Haitians have died and 746,000

have been sickened by what mushroomed into the world’s

worst cholera epidemic. Five

years ago this month, the first cases of cholera in more

than a century started to multiply in Haiti’s Artibonite

Valley. Today, some 9,000 Haitians have died and 746,000

have been sickened by what mushroomed into the world’s

worst cholera epidemic.

United Nations

troops from Nepal brought the disease into Haiti,

several scientific studies have definitively

established. Sewage from their outhouses leaked into the

headwaters of the Artibonite, Haiti’s largest river,

which is used for irrigation, bathing, and drinking

water.

Nonetheless, the UN continues to reject any

responsibility for its negligence in unleashing cholera

in Haiti, despite two on-going lawsuits against it.

The Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti

(IJDH) was the

first to bring suit within the

UN’s own grievance structure back in November

2011. This went nowhere, and the IJDH had to pursue its

lawsuit in U.S. District Court in New York. In January,

U.S. District Judge J. Paul Oetken

ruled that the UN had immunity

from prosecution. The IJDH has

appealed that

decision.

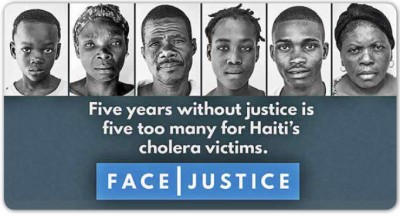

To mark the outbreak’s grim anniversary, on Wed.,

Oct. 14, cholera justice activists will erect large

portraits of cholera victims outside UN headquarters in

New York, Geneva, and Port-au-Prince. The action also

comes on the eve of the renewal for a 12th

year of the country’s highly unpopular and illegal

international military occupation known as the “UN

Mission to Stabilize Haiti” (MINUSTAH), first

deployed on Jun. 1, 2004. A common

sign seen at demonstrations in Haiti is: “MINUSTAH =

Cholera.”

The portraits will mutely but powerfully accuse

the UN of impunity and are a part of a new campaign,

Face Justice,

which calls on the UN to hear victims’ calls for

justice. The campaign demands that the UN accept

responsibility for causing the epidemic through faulty

waste management, provide reparations, and invest in

water and sanitation to eliminate cholera.

“Every family in my community lost something

because UN peacekeepers gave us cholera,” said Joseph

Dade Guiwil, a cholera survivor whose portrait will be

featured at the UN. “I say to the UN: give us justice.”

The exhibition of giant photographic portraits is

done in partnership with the

Inside Out Project,

pioneered by French photographer/artist JR. Having won a

$100,000 TED Prize

in 2010, JR launched the Inside Out project as “a global

participatory art project with the potential to change

the world,” according to the project’s website. Inside

Out has displayed huge head shot posters on buildings,

in fields, and in plazas in dozens of countries around

the globe to

advance causes as

diverse as

Black Lives Matter,

saving the Arctic,

clean air in Belgium,

and

education improvement in

Tanzania.

The “Face Justice” photo exhibits to debut on

Oct. 14 will feature the diverse faces of Haiti’s

cholera victims, including Pierre Louis Fedline, 9, who

was orphaned by cholera, and Renette Viergélan, who was

hospitalized with cholera when her 10-month old baby

contracted it and died.

“We are doing this to remind the UN that victims

of cholera are not just numbers – they are real people,”

said Jimy Mertune, an activist with the Haitian diaspora

group Collective of Solidarity for Cholera Victims.

“They could be my uncle, my father, my sister, my

brother. My children.”

Despite Judge Oetken’s ruling, support for

cholera justice continues to grow. On Oct. 13, Amnesty

International

issued a strongly worded

statement condemning the UN’s stance.

“The UN must not just wash its hands of the human

suffering and pain that it has caused,” said Erika

Guevara Rosas, Americas Director at Amnesty

International. “Setting up general health programs and

sanitation campaigns is important but not enough. What

is needed now is a proper investigation into the full

extent of the damages caused, and a detailed plan to

help those who have fallen victim to this disease and

the relatives of those who have died. Failing to take

action will only undermine the UN’s credibility and

responsibility as a promoter of human rights across the

world.”

In July, 154 Haitian diaspora community

organizations along with political, religious, media,

union, and other diaspora leaders issued

an open letter to

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and UN Secretary

General Ban Ki-Moon “ to express our deep outrage at the

United Nations’ failure to take responsibility for the

cholera epidemic it brought to Haiti.” Calling the UN’s

half-hearted focus on improving sanitation

“disingenuous,” the Haitian diaspora leaders slammed the

UN’s “refusal to comply with its legal obligations to

Haiti’s cholera victims [which] denies it the

credibility necessary to effectively promote the rule of

law in Haiti. It also sets a dangerous example about the

ability of the powerful to avoid justice, which will

come back to haunt Haitians.”

Even four high-level UN officials sent an

official

Allegation Letter in

September 2014 to the Secretary General Ban to “express

serious concern” that the UN “failed to take reasonable

precautions and act with due diligence to prevent the

introduction and the outbreak of cholera in Haiti since

2010,” that those “affected by the cholera outbreak have

been denied access to legal remedies and have not

received compensation,” and that “efforts to combat

cholera and to improve the water and sanitation

facilities in Haiti have been inadequate.”

Meanwhile, on the legal front, the IJDH’s appeal

of the January dismissal has “a wide number of

supporters, including former UN officers, who have

submitted amicus

curiae [friend of the court] briefs in support of

the plaintiffs,” IJDH lawyer Beatrice Lindstrom told

Haïti Liberté.

“The U.S. government has continued to ask the court for

dismissal based on UN immunity, and we just submitted

our last brief at the end of September. We're now

waiting to hear if there will be oral argument.”

In Haiti, several thousand people are expected to

gather for a demonstration outside the UN Logistics Base

at the Port-au-Prince airport on Oct. 15.

Face Justice

is also sending to UN member states post cards with

cholera victims’ photos and appeals for justice.

“We hope these personal images and stories will

cause more people at the UN to consider the human toll

of cholera and to understand that the UN’s inadequate

response ignores the dignity of each victim and the

severity of their loss,” said Katharine Oswald, Policy

Analyst and Advocacy Coordinator for the Mennonite

Central Committee in Haiti, who worked with victims to

document their stories.

For

more information about the campaign, visit

facejustice.org.

Photos from the portrait display will be available to

the media on Oct. 14.

|