|

Every definable chapter of recent Haitian history seems

to have one book which becomes the definitive reference

for English speakers. Amy Wilentz’s “The Rainy Season” (1986-1989), Peter Hallward’s “Damming

the Flood” (2000-2006), and Jonathan Katz’s “The

Big Truck That Went By” (years around the 2010

earthquake) come to mind.

All of those examples, however, were written by

foreigners. For the period of the rise and fall of

President Michel Martelly (roughly 2010 to 2015), the

definitive account at this point is surely “We

Have Dared to be Free: Haiti’s Struggle Against

Occupation” (News Junkie Post Press, 2015), written

by Haitian scientist turned journalist Dady Chery.

But the book is much more than a recapitulation

and analysis of government malfeasance and popular

resistance during the years of the recently departed

Martelly regime. It is a stirring and unflinching

indictment of world capitalism, presented through the

prism of the Haitian history, traditions, and culture.

It leaps from macro to micro and back, through a

patchwork of personal reminiscences, interviews,

scientific explanations, and historical accounts which

illuminate, not just Haiti, but the state of the world

today.

“We can visualize a world where Haiti’s

revolution has expanded to all of humanity and become a

final push for the birth of all humans into their full

potential, and more than anything, into a respect for

the other that borders on a religion, with the

understanding that we are part of all the life that

makes up this era on Earth,” Chery writes in a

tour-de-force introduction. “Haiti’s example of the

first successful anti-capitalist, anti-imperial, and

anti-colonial revolution in a world where slavery was in

vogue, showed what humans could do in the face of

impossible odds.”

Throughout the book, the author, proud of her

“magical childhood” in the Haitian countryside, argues

that, in many ways, Haiti offers a model of how the

human race can survive in the face of the ecological and

economic tsunamis on the horizon. “In addition to a

categorical rejection of racism, at the base of all

Haitian conduct was also a rejection of slavery: the

philosophy that one does not live to work, but one works

to earn enough to celebrate life by developing one’s

talents,” she writes. “Such an idea is contrary to the

capitalist notion of ever growing consumption that

follows the failing model of endless economic growth.”

As the title suggests, the author carefully

catalogues the crimes of the on-going 12 year United

Nations military occupation known as the UN Mission to

Stabilize Haiti or MINUSTAH, including “gunrunning,

trading food for sex, cholera contamination, human

trafficking, child prostitution, rape, murders, and

massacres.”

She also lays out the role of the Clintons,

particularly Bill Clinton as the co-chair of the Interim

Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC). “From the start, Bill

Clinton’s IHRC, an international group of wealthy

businessmen, backed by an expanded army from MINUSTAH,

forced themselves on the country to make it liquidate

its commons to them and their friends at fire-sale

prices,” Chery writes. She details the popular

resistance to the IHRC and an associated State of

Emergency Law “which allowed a takeover of Haiti’s

reconstruction efforts formally for 18 months in

principle, but really for as long as possible, by a

group of wealthy foreign donors who would operate

without any liability for their actions.”

Chery is a college biology professor in the U.S.,

and throughout “We

Have Dared to be Free” are detailed scientific

presentations on a host of matters: climate change,

Haiti’s cholera epidemic and its solution (sanitation,

not vaccines), the kidnapping of Haiti’s endangered

wildlife species, gold mining, etc.

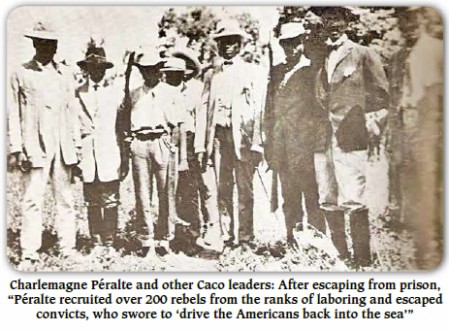

The structure of the book is unconventional.

Rather than the customary recitation of Haitian history

at the book’s beginning, Chery places her detailed

treatment of key episodes in Haiti’s story towards the

middle and the end. Chapter 11 gives an in-depth

explanation of rebel leader Charlemagne Péralte and the

Caco guerillas who fought the 1915-1934 U.S. Marine

occupation of Haiti, and Chapter 21 (of 23 total) gives

a similarly detailed account and analysis of Toussaint

L’Ouverture, the leader of the successful slave

revolution in the colony of St. Domingue.

Chery also slaughters many sacred cows. I

particularly liked her spirited defense of the

institution of

restavek, which is often presented by North American

liberals as child slavery. “One cannot talk about

orphaned Haitian children without confronting two highly

controversial and interwoven subjects:

Vodou and

restavek,”

Chery writes. “Both are part of the very fabric of the

Haitian family, which is currently under vicious

attack.”

Chery’s mother had been a

restavek in

her grandparents’ home, and she relates many anecdotes

to argue that the “restavek

system is profoundly subversive in that it intimately

binds Haitians of different socioeconomic classes.”

Similarly, the author makes a clear explanation

and strong defense of vodou: “The practices of Haitian

Vodou represent religion, unadulterated, unappropriated,

and at its best: not an infantilizing force that

habituates people to their prostration before a greater

power, but a cultural force that anchors people in the

lands and waters around them and furnishes them with the

practices for a joyful, sustainable life.”

Many parts of the book are drawn from the

author’s Haiti Chery blog (www.dadychery.org),

such as her detailed review of the Martelly government’s

unilateral attempts to transform the bucolic Ile à Vache

(Cow Island), just off Aux Cayes, into a tourist

complex, without consulting with the island’s

population. The author interviewed the leaders of the

resistance that emerged and explains why and how the

take-over foundered.

Chery takes to task some progressive U.S.

journalists and intellectuals, charging them with being

“high priests of journalism” who “promote the neoliberal

agenda and encapsulate their disinformation in

reasonable seeming and progressive-sounding language.”

In her zeal to defend Haiti against the undeniable

“propaganda war” and “disinformation campaign” waged

against it, Chery may be blasting writers who are not

the enemy, a little like an overactive immune system

causes an allergic response. There surely is historical

confusion, factual sloppiness, formulaic reasoning, and

idolatry

in some “leftist” writings on Haiti, and Chery’s

indignation will make any well-meaning writer deeply

reflect on whether their arguments do not bring water to

neoliberalism’s mill in Haiti.

Similarly, Chery critiques “supposedly leftist

governments like those of Ecuador, Argentina, Bolivia,

Uruguay and Venezuela [which] have also eagerly

supported the [Martelly] regime under the pretext that

they would not wish to abandon Haiti to the U.S..” She

should have noted, however, that Venezuela, for one,

never joined MINUSTAH. Furthermore, officials from both

the governments of the late Hugo Chavez and Nicolas

Maduro have always defended their dealings with Martelly

by saying that they would honor Venezuela’s commitments

to the Haitian people (made under President René Préval)

whether they liked Haiti’s political representatives or

not, a principled approach with contrasts sharply with

that of Washington.

There are quite a few detours in

“We Have Dared to

be Free.” Chery goes into great depth on the 2010

coup d’état attempt in Ecuador, on how a warming planet

causes stronger storms and what damage they have caused

worldwide, and on the history and tactics of Martin

Luther King, Jr.

But all these detours lead back to her central

and often revisited central thesis: “The systematic

destruction of Haiti, if it is allowed to continue, will

not be Haiti’s loss alone. Gone will be a cheerful and

sustainable way of life, the taste for being sated with

enough, which we must all learn to recover for the sake

of our species’ survival.”

As Chery also notes in her introduction: “If

Haiti is a model of the world’s depredations, it is also

a testament to human resistance.”

Haiti’s 2010 earthquake awakened the engaged journalist

lying dormant in a biology professor simply pursuing her

career. “We Have

Dared to be Free” is the result, a passionate and

scientific argument for how Haiti still offers humanity

an example to be followed.

|