|

Christian Guerrier and Brian

Jackson, both based in the Miami,

Florida area, visited Haiti from Feb. 1

- 9. They are with the Millennials Project,

an organization dedicated to the

empowerment of women.

We traveled to Haiti with the idea

that women would emerge to lead

in rebuilding and reshaping the country’s

future after the devastating Jan.

12th earthquake. Arriving by bus from

the Dominican Republic, we stayed in

makeshift tents at Port-au-Prince’s Carrefour

Aviation Base, near the community

of Pont Rouge, where Christian had

lived as a boy.

Prior to our arrival, we had heard

from news reports that women were

having difficulty obtaining the aid that

was being distributed. When we arrived,

it appeared that nobody was receiving

such aid. It was quite clear that the most

pressing need among the hundreds of

thousands of internally displaced was

tents. Having toured much of Port–au–

Prince by car, we had observed no more

than a few hundred tents spread between

a handful of locations. Throughout the

week, we spent the better part of our

time organizing the women at Carrefour

Aviation and going back and forth to

the United Nation’s Mission to Stabilize

Haiti (MINUSTAH) Logistics Base, in the

airport’s northeast corner, where most of

the foreign aid groups were stationed.

We spoke with no less than two dozen

representatives from organizations such

as the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF),

the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the

International Organization for Migration

(IOM), The Red Cross, the World Health

Organization (WHO) and the UN World

Food Programme (WFP), none of whom

could tell us how many tents were available,

where they were, or why they

were not being distributed.

The general consensus was that

IOM was primarily responsible for the

handling of tents, however, when we

met with its representative, Louis (no

last name provided), he claimed that the

organization’s resources had dried up,

that there was no cache of tents waiting

for distribution. “Unless the American

people decide to turn the tap back on,

there’s nothing we can do,” he said.

The following day, we met a UNHCR

representative. The organization

supplies tents for the camps of many

internally displaced people around the

world, but it is not mandated to work

in Haiti. He explained to us that UNHCR

had offered to provide additional

tents, but was told by the IOM that it

had “more than enough.”

We fi nally attempted to have a

group of eight women from the Pont

Rouge community admitted to the MINUSTAH

Base to speak directly with the

representatives of these NGOs, who generally

did not want to cooperate with the

Millenials Project, it being a new U.S.-

based organization that they had never

heard of. These women (called the Haitian

Women’s Leadership Council) could

assess and articulate the needs of their

community better than any foreign team

of aid workers possibly could, and they

were willing and able to coordinate the

distribution of materials. Despite making

the effort of traveling to the MINUSTAH

Base, the women were not even allowed

in the gate of the walled-in compound.

The two of us went into the base to talk

with NGO representatives, but they refused

to admit the women’s delegation.

It was turned away.

After getting no help and no answers

except those that we ourselves

were able to deduce from a series of

verbal inconsistencies, we decided with

the women to organize a public demonstration.

Since the Haitian Women’s

Leadership Council would not be admitted

into the MINUSTAH base to voice

their concerns, we chose to have a

mass march to the base the following

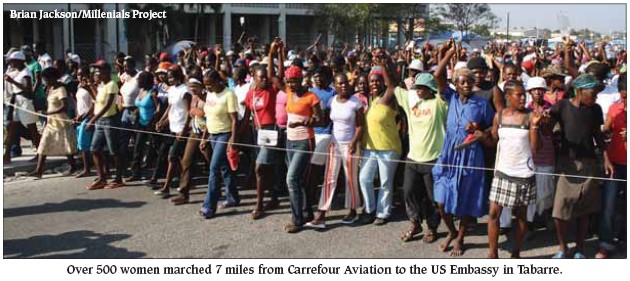

day. Throughout the week, huge rallies

had been taking place each afternoon

at an amphitheater located in the Carrefour

Aviation area. By Thursday, Feb.

4, we had amassed about 500 people

from the community |