|

Last May, the

United Nations announced “6.7 million Haitians face food

insecurity.” Aid organizations, development agencies, and the

media mobilized with articles, videos, and “urgent appeals.”

Thanks to some measures, and also some good weather, the numbers

have likely improved slightly since then. Recently, the

Coordination Nationale de Securité Alimentaire (CNSA or

National Coordination for Food Security) announced that rice and

corn harvests are up from the year before. (However, they remain

below previous years.)

Nevertheless, with terrifying charts and dire warnings,

officials continue to say that in 2013, twice as many Haitians

as last year – some 1.5 million people – continue to face

“severe” or “acute food insecurity,” and that many millions more

are considered food insecure. At least one-fifth, and in some

areas, one-third, of all Haitian children are “stunted,” meaning

that they are underweight, shorter than they ought to be, and

the development of their brains and other organs will likely be

affected.

Hunger has also become part of the political football game in

Haiti.

Speaking on May 10, former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide

criticized the government for not addressing the hunger problem

and gave a thinly veiled warning, quoting a Haitian proverb:

“When a dog is hungry, it doesn't play around."

President Michel Martelly responded a few days later, saying

Aristide was telling “a lie” and that he is also responsible

since “he spent ten years in power.” (Actually, Aristide did not

spend ten years in office. Both terms were truncated by coups).

While

statistically hard to verify, many reports say hunger in Haiti

today is more pervasive than it has ever been in the last 50

years.

Doudou Pierre Festil, a farmer who is also member of a national

peasant movement and the coordinator of a network of about 200

farmers associations and other organizations known as Réseau

National Haïtien pour la Souveraineté et la Sécurité Alimentaire

(RENAHSSA – National Network for Sovereignty and Food Security),

says “the government is 100% responsible” for hunger in Haiti.

But

the reality is more nuanced, the causes of hunger more

structural.

Everyone has been aware of Haiti’s brewing food crisis for

years: Haitian agronomists, economists, farmers, and government

officials, foreign donors and humanitarian agencies. Over they

years, Haitian and foreign “experts” have designed projects,

written grants… and they have also executed contracts and been

well-paid for their services.

Over

the past four decades, donors have spent billions of dollars on

“food aid,” “development aid,” “humanitarian assistance,” and a

host of agricultural programs.

Haiti

Grassroots Watch (HGW) and many others know that the causes of

hunger are structural, some of them dating back to the earliest

days of the republic. They are also interrelated and linked to

larger economic issues in the country and in the world. While it

is not possible to explore the causes in depth in this series,

here is a summary of the most obvious causes.

1) Poverty.

One-half of the population lives on less than US$1 per day; some

three-quarters live on less than US$2 per day. With little to no

buying power, Haitians who do not produce their own food do not

have the income necessary to buy even basic necessities. One

thing that makes Haitians poorer, a recent UN mission report

noted, is that “basic social services” – like education – have

to be purchased, further stressing poor households.

2) Haiti’s

land tenure system and lack of correct land-management.

According to Bernard Ethéart, an expert on Haitian land issues

and former director of the Institut Nationale de la Réforme

Agraire (INARA – the National Institute of Land Reform),

Haiti’s land tenure system is a “complete disorder that has been

going on for 200 years.” Ethéart claims that most land belongs

to the government, because ever since independence, various

dictators have stolen, illegally “sold,” or given away parcels

to their families and their allies. Haiti has no land registry.

In the countryside, land security is quite low because many

“owners” do not have titles or have titles that are out-of-date.

In addition, a great deal of farmland is either state land

leased from the government, or is “owned” by large landowner (grandon)

who then rents it or has sharecroppers (known as “demwatye”)

work it. Thus in many cases, farmers are not invested in the

land. Studies have shown that farmers working leased, rented, or

share-cropped land are less likely to protect it from

deforestation and other practices that weaken the soil and the

environment. Another challenge is the fact that “private” land

is divided into tiny plots because Haitian law says all

offspring have a right to inherit a portion their parent’s land.

3) Neoliberal

trade policies. The World

Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the U.S.

government have pushed neoliberal economic policies on Haitian

governments since the 1980s. In 1995, under pressure from

Washington, the Aristide government dropped tariffs on many food

products to zero or near-zero: making then the lowest tariffs in

the Caribbean at that time. A 2006 Christian Aid report

noted: “[T]he results of lowering agricultural tariffs in Haiti

have been disastrous.” Trade liberalization is directly linked

to decreased agricultural production, increased rural poverty,

an exodus from the countryside into city slums, and increasing

hunger, according to Christian Aid and many other

experts. The radical policies came on top of 200 years of having

what Haitian economist Fred Doura calls an “extraverted”

economy, which is “exploited and dominated” by foreign

countries, their economies, their currencies, and their needs:

first France, then the United States. In Haïti – Histoire et

analyse d’une extraversion dépendent organisée, Doura says

that Haiti’s dependence is cultural, technological, financial,

and also economic, given that since its inception, much of the

country’s production has been exported while its necessities

were imported. Doura laments: “The neoliberal globalization of

the economy has reinforced the vise of Haiti’s dependence.”

4) Population

increase coupled with stagnant or declining agricultural output.

This has taken place due to many interrelated reasons,

including:

- The land tenure

system.

- Decades of an

overall lack of government and donor investment in agriculture.

For example, during the first half of the 2000s, the Agriculture

Ministry received only 4% of the budget, while agriculture and

rural development accounted for only 2.5% of official

development assistance. A 2009 UN mission deplored “the abandon

of agricultural sector and of national production for the past

three decades.” The mission also noted that the approach of the

government and various organizations at the time was

characterized by “multiple strategies and programs which are

sometimes contradictory and by endless conferences which do not

deliver any concrete results.”

- Antiquated

methods and techniques, lack of access to fertilizers and

improved seeds, and other challenges due to the lack of state

support.

- Lack of

efficient and maintained irrigation systems.

- Crop loss due

to the lack of a road system that can safely and efficiently get

produce to markets and/or the lack of adequate food storage

facilities.

- Lack of

enforcement of a tree-cutting ban, and the lack of an energy

policy, which discourages charcoal as an energy source, both of

which contribute to deforestation.

- Vulnerability

to tropical weather events like droughts and flooding due to

massive deforestation and other results of failure to manage the

environment.

- Declining soil

quality caused, in part, by increased run-off due to

deforestation.

- Emigration of

youth from farming areas due to lack of schools, other services,

and economic opportunity, and the ensuing lack of farmers and

farm workers in the countryside.

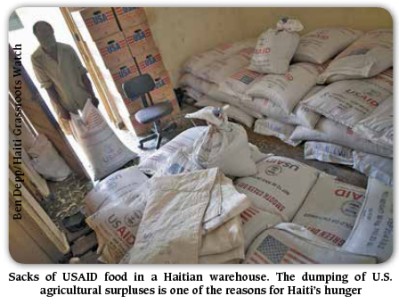

5) Negative

impacts from various food aid practices over the past 55 years

Other failures or

negative results of “aid” mechanisms. The Haitian government

told the UN mission that foreign donors shy away from budgetary

support and that this is one of many stumbling blocks. According

to the UN Office of the Special Envoy, in 2007, for example,

bilateral donors gave only 3% of their aid to budget support,

while multilateral donors gave only 16%. All the rest of foreign

aid went to agencies and projects. Also, the 2009 UN mission

criticized a decade or more of focusing on “emergencies” rather

than structural causes of hunger, declining agricultural

production, environmental degradation, and other linked

structural issues. The mission also criticized the results of

“the perverse mechanism of handouts like farmers waiting for

free fertilizer, the failure to clean certain canals in the

hopes that an NGO will pay for it…”

6) Internal market inefficiencies,

especially what one U.S. government report called “oligopolistic

practices” by food importers. The rice market, for example, is

dominated by three major import companies, which are controlled

by three members of Haiti’s elite. A 2010 study noted that

“rather than undercutting one another’s prices, Haiti’s major

importers collude to agree on prices.” This results in local

prices that are unnecessarily high and are sometimes much higher

than on the international market. One importer admitted to the

study author: “If this were the U.S., we would go to jail.”

|