|

In his new book, Ricardo

Seitenfus writes about the “electoral coup” which brought

President Martelly to power, the UN’s “genocide by negligence”

through importing cholera, and Venezuela’s “new paradigm” with

PetroCaribe

(First of

two parts)*

(Part 2)The

title of Brazilian professor Ricardo Seitenfus’ book, HAITI:

Dilemas e Fracassos Internacionais (“International

Crossroads and Failures in Haiti,” published in Brazil by the

Editora Unijui – Universite de Ijui– in the series Globalization

and International Relations) appropriately opens with a

reference to existentialist philosopher Albert Camus.

Camus’ third great novel, The Fall,

is a work of fiction in which the author makes the case that

every living person is responsible for any atrocity that can be

quantified or named. In the case of Haiti, the January 2010

earthquake set the final stage for what amounted to what

Seitenfus says is an “international embezzlement” of the

country.

The tragedy began over 200 years ago in

1804, when Haiti committed what Seitenfus terms an “original

sin,” a crime of lèse-majesté for a troubled world: it

became the first (and only) independent nation to emerge from a

slave rebellion. “The Haitian revolutionary model scared the

colonialist and racist Great Powers,” Seitenfus writes. The U.S.

only recognized Haiti’s independence in 1862, just before it

abolished its own slavery system, and France demanded heavy

financial compensation from the new republic as a condition of

its honoring Haiti’s nationhood. Haiti has been isolated and

manipulated on the international scene ever since, its people

“prisoners on their own island.”

To understand Seitenfus’ journey into the

theater of the absurd, it is necessary to revisit the months

after the 2010 Haiti earthquake. As the Organization of American

States’ (OAS) Special Representative in Haiti, Seitenfus lost

his job in December 2010 after an interview in which he sharply

criticized the role of the United Nations and non-governmental

organizations (NGOs) in the devastated country. But it appears

that the author also had insider information about international

plans for a “silent coup d’etat,” electoral interference and

more.

On the Ground in Haiti: October-December

2010

It was not yet one year since a 7.0

magnitude earthquake killed 220,000 or more, left infrastructure

in chaos, and 1.5 million people homeless. Accusations were

rampant in October international press reports that the United

Nations mission to Haiti (MINUSTAH) had introduced cholera into

Haiti’s river system. As of Feb. 9, 2014, 699,244 people

contracted cholera and 8,549 have died.

Ground zero for the outbreak was negligent

sewage disposal at the Nepalese Mirebalais MINUSTAH camp. The

malfeasance was first documented by the Associated Press and

ultimately provided crucial proof of the U.N.’s guilt. Thousands

were infected and the number of dead rose exponentially. On Nov.

28, the national election was contested in what can only be

termed an electoral crisis. Hundreds of thousands of voters were

either shut out of the electoral process or boycotted the vote

after the most popular party in the country — Fanmi Lavalas —

was again banned from competing. Many of those displaced by the

earthquake were not allowed to vote, and in the end less than

23% of registered voters had their vote counted.

Eyewitness testimony on election day

reported numerous electoral violations: ballot stuffing, tearing

up of ballots, intimidation and fraud. Haiti’s Provisional

Electoral Council , responsible for overseeing elections,

announced that former first lady Mirlande Manigat won but lacked

the margin of victory needed to avoid a runoff. An OAS “experts”

mission was dispatched to examine the results. Even though it

was indeterminate that he should advance, due to the OAS’

intervention, candidate and pop musician Michel “Sweet Micky”

Martelly was selected to compete in the runoff instead of the

governing party’s candidate Jude Célestin.

The Center for Economic and Policy Research

(CEPR) subsequently released a report showing that there were so

many problems with the election tallies that the OAS’

conclusions represented a political, rather than an electoral

decision.

CEPR reported that for some 1,326 voting

booths, or 11.9% of the total, tally sheets were either never

received by the CEP, or were quarantined for irregularities.

This corresponded to about 12.7% of the vote not being counted

and not included in the final totals that were released by the

CEP on Dec. 7, 2010 and reported by the press. CEPR also noted

that in its review of the tally sheets, the OAS Mission chose to

examine only a portion, and that those it discarded were from

disproportionately pro-Célestin areas. Nor did the OAS mission

use any statistical inference to estimate what might have

resulted had it examined the other 92% of tally sheets that it

did not examine.

The runoff was finally scheduled for Mar.

20, 2011 and Martelly was declared the winner with 67.6% of the

vote versus Manigat’s 31.5%. Turnout was so low that Martelly

was declared president-elect after receiving the votes of less

than 17% of the electorate in the second round.

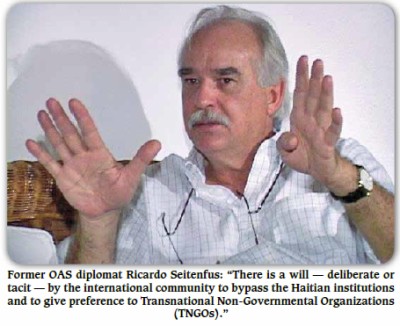

Into the fray stepped Brazilian professor

Ricardo Seitenfus. Seitenfus, a respected scholar, made

statements to Swiss newspaper Le Temps criticizing

international meddling in Haiti in general and by MINUSTAH and

NGOs in particular. He was abruptly ousted on Christmas Day. The

press was equivocal on whether Seitenfus was fired or forced to

take a two-month “vacation” before his tenure ended in March

2011.

Was Seitenfus let go for citing a “maléfique

ou perverse” (evil or perverse) relationship between the

government of Haiti and NGOs operating amidst fraud and waste;

his accusations about the cholera cover-up; or more troubling,

knowledge of a silent coup being orchestrated against

then-President Rene Préval by a secret “Core Group?” Was he

silenced because of his knowledge of covert meetings between the

then Special Representative of the Secretary-General and

MINUSTAH chief Edmond Mulet, then U.S Ambassador Kenneth Merten,

and then-Prime Minister Jean-Max Bellerive?

Seitenfus’ passionate accounting of the

events in the year after the January 2010 earthquake reveals a

man seemingly at odds with his internal moral compass and what

he describes as “the black hole of western consciousness” in

relations between Haiti and the international community of donor

nations. This is a book written by a man enthralled by the

beauty and promise of Haiti. It is also a book written by a

professor serving as a diplomat struggling to be a whistleblower

in the absurd and troubling world of international diplomacy.

Q: You write about

international collusion in plans for a “silent coup.” Why wait

until now to name the perpetrators? Does the fact that Mulet,

Bellerive and Merten have all moved on from their offices have

anything to do with your timing? You state emphatically that you

opposed the coup plans.

RS: No. It is not true that I kept

quiet. I gave various interviews to the Brazilian and

international press, in late December 2010 and early January

2011, mentioning this and other episodes. See, for example, the

BBC and AlJazeera.

The problem is that the international press

was manipulated during the electoral crisis and never had an

interest in doing investigative journalism. In the interviews

that I gave, and especially in my book (“International

Crossroads and Failures in Haiti”), soon to be published in

Brazil and other countries, I describe the electoral coup in

great detail.

Furthermore, the vast majority of the

elements I reveal, I discovered in a scientific research project

over the past three years. Many questions were hanging in the

air, without adequate answers. I believe I managed to connect

the different views and actors, providing the reader a logical

and consistent interpretation about what happened. We are

dealing with a work that is required by the historical memory,

without any shadow of revenge or settling of scores.

Q: Were you the background

press source on early reports of the cholera epidemic being

caused by MINUSTAH in October 2010? You write about the

“shameless” attitude of the United Nations (including Edmond

Mulet and Ban Ki-moon) and ambassadors of the so-called “friends

of Haiti;” countries that refused to take responsibility after

MINUSTAH introduced cholera to Haiti. You say that this

“transforms this peace mission into one of the worst in the

history of the United Nations.” Would you be willing to testify

in the current class action lawsuit, filed in a U.S. federal

court, accusing the U.N. of gross negligence and misconduct on

behalf of cholera victims in Haiti?

RS: There is no doubt that the fact

that the United Nations — especially Edmond Mulet and Ban Ki-moon

— systematically denied its direct and scientifically-verified

responsibility for the introduction of the Vibrio cholera into

Haiti, projects a lasting shadow over that peace operation. What

is shocking is not MINUSTAH’s carelessness and negligence. What

is shocking is the lie, turned into strategy, by the

international community. The connivance of the alleged “Group of

Friends of Haiti” (integrated at first by Argentina, the

Bahamas, Belize, Canada, Chile, the United States, Guatemala,

Mexico, the Dominican Republic and Venezuela, as well as

Germany, France, Spain and Norway, in their role as Permanent

Observers before the OAS) in this genocide by negligence,

constitutes an embarrassment that will forever mark their

relations with Haiti.

Even former President Clinton, in a visit

in early March 2012 to a hospital in the central region of

Haiti, publicly admitted that “I don’t know that the person who

introduced cholera in Haiti, the U.N. peacekeeper, or [U.N.]

soldier from South Asia, was aware that he was carrying the

virus. It was the proximate cause of cholera. That is, he was

carrying the cholera strain. It came from his waste stream into

the waterways of Haiti, into the bodies of Haitians.” [1]

Although soon after he stated that the

absence of a sanitation system in Haiti propagated the epidemic,

these statements by the Special Envoy of the U.N. Secretary

General for Haiti represent the first major fissure in the

denial strategy of the crime committed by the United Nations.

Currently, the United Nations hides behind

the immunity clause conferred by the Jul. 9, 2004 agreement

signed with Haiti legalizing MINUSTAH’s existence. Now, this

agreement is void, since it was not signed, as provided in the

Haitian Constitution (Article 139), by the Acting President of

Haiti, Boniface Alexandre, but by the PM [Prime Minister] Gerard

Latortue. According to the 1969 and 1986 Vienna Conventions on

the Law of Treaties, any treaty signed by someone who lacks

jus tractum — that is, treaty making power — is null and

considered ineffective.

As with any legal action, without validity

it has no [legal] effect. The existence of a lack of consent —

whether due to the inability of state representatives to

conclude a treaty or to an imperfect ratification — results in

the absolute voiding of the action (Vienna Convention, Article

46, paragraph 1).

With the contempt for Haitian

constitutional rites and for the legal principles that govern

the Law of Treaties, the United Nations demonstrated, once

again, the constant levity with which it treats Haitian matters.

Responsible for establishing the rule of law in the country,

according to its own mission, the UN does not follow even its

own fundamental provisions, thus making the text that it

supports and that should legalize its actions in Haiti void and

ineffective.

Therefore, the UN’s last recourse in trying

to deny its responsibility for introducing cholera in Haiti can

be easily circumvented, since MINUSTAH’s very existence is

plagued with illegalities.

Clearly, I am and will always be available

to any judicial power that deals with this case. Even federal

courts in the United States. If asked, I will testify, with the

goal of contributing to establish the truth of the facts and the

search for justice.

Q: Were you threatened in

any way prior to your departure from Haiti? Since you were

effectively fired, why not name names and discuss the actions of

the “Core Group” in 2010?

RS: As a coordination agency for the

main foreign actors (states and international organizations) in

Haiti, a limited Core Group (which includes Brazil, Canada,

Spain, the United States, France, the UN, the OAS and the

European Union) is an indispensable and fundamental instrument

in the relations between the international community and the

Haitian government. It is not about questioning its existence.

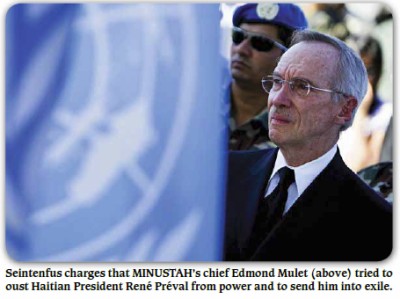

What I was able to verify was that on [election day] Nov. 28,

2010, in the absence of any discussion or decision about the

matter, [then head of MINUSTAH] Edmond Mulet, speaking on behalf

of the Core Group, tried to remove [then president of Haiti]

René Préval from power and to send him into exile. Meanwhile,

the U.S. Embassy in Port-au-Prince published a press release at

9 p.m. the same day dismissing the voting results and imposing

its position on the whole Core Group. Still, the majority of the

decisions in which I participated as representative to the OAS

in the Core Group during the years 2009 and 2010 were sensible

and important.

Q: You write about the

“maléfique ou perverse” (evil or perverse) relationship between

NGOs and Haiti. In your view, has this problem become

institutionalized? You said some of the NGOs exist only because

of Haitian misfortune?

RS: There is a will — deliberate or

tacit — by the international community to bypass the Haitian

institutions and to give preference to Transnational

Non-Governmental Organizations (TNGOs). [2] Their overwhelming

invasion following the earthquake reached levels never before

imagined. [Then] U.S. Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton,

herself pointed out in an interview some months after the

earthquake that more than 10,000 TNGOs were operating in Haiti.

This means that there was an increase in their presence of over

4,000% in the course of a short period of time. This NGOization

turns Haiti into what many have called a true “Republic of the

TNGOs.”

In the face of a weakened state and one

that was almost destroyed by the earthquake, the emergency aid

apparatus had no option but to directly confront reality. Direct

connections were established with the victims and even those in

charge of the UN system in Haiti were not taken into account. A

true pandemonium came into being in which everyone decided on

his own what to do, and when and how to do it.

An optimistic and official report,

presented by Ban Ki-moon to the UN Security Council in October

2012, recognizes that of the alleged US$ 5.78 billion in

contributions made over the 2010-2012 period by bilateral and

multilateral donors, a little less than 10% (US$ 556 million)

was given to the Haitian government. It is worth mentioning that

the governments of the donor states use both private donations

and public resources to cover the spending of their own

interventions in Haiti. As such, for example, more than US$ 200

million in private donations from U.S. citizens served to

finance the transportation and stay of U.S. soldiers in Haiti

soon after the earthquake.

Traditionally in Haiti, the “goods” such as

hospitals, schools and humanitarian aid are delivered by the

private sector, while the “bads” — that is, police enforcement —

is the state’s responsibility. The earthquake further deepened

this terrible dichotomy.

The circle was closed with the ideological

discourse to justify this way of proceeding. According to this

[discourse], the transfer of resources is done through the TNGOs

for the simple reason that the Haitian state suffers from total

and permanent corruption. Sometimes, the lack of managerial

capacity is cited. Therefore, there is nothing more logical than

to bypass public authorities without even thinking that without

a structured and effective state, no human society has managed

to develop.

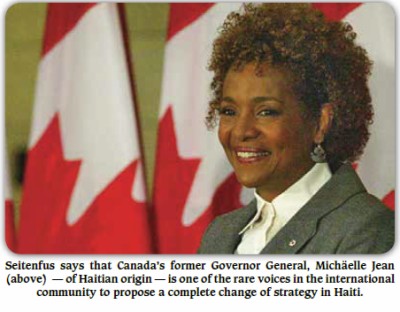

The former Governor General of Canada,

Michäelle Jean — of Haitian origin — is one of the rare voices

in the international community to propose a complete change of

strategy. To her,

“Charity comes from the heart, but

sometimes, when it’s poorly organized, it contributes more to

the problems than to the solutions. Haiti is among the countries

that’s been transformed into a vast laboratory of all the

experiments, all the tests, and all the errors of the

international aid system; of the faulty strategies that have

never generated results, that have never produced or achieved

anything that’s really sustainable despite the millions of

dollars amassed in total disorder, without long term vision and

in a completely scattered fashion.” [3]

Certainly, direct financial cooperation

with a state that has a lack of administrative capacity

increases the risk that resources will be misused. However,

there is no other solution: either the public management

capacity of the Haitian state is strengthened or we will keep

plowing the sea.

Unfortunately, the international community

prefers to continue with the strategy that has already proved to

be thoroughly inefficient. It not only impedes financial

transfers to Haitian institutions, but it also tries to force

them to channel their own meager resources to be administrated

by international organizations. There was, for example, an

attempt to transfer the PetroCaribe fund resources for Haiti to

the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission. The determined resistance

by Préval and Bellerive terminated this move. Nonetheless, in

every election campaign, the donor countries insist on having

the resources of the Haitian treasury be administered by the UN

Development Program (UNDP). Therefore, the strategy of the

international community not only impedes institutional

strengthening, but it also takes away from the Haitian state the

little financial autonomy that it possesses.

The model imposed on Haiti since 2004 has

two elements. On the one hand, there is the military presence

through MINUSTAH, and on the other the civil presence in the

form of the TNGOs and the alleged private development

corporations. Added to these are the bilateral strategies of the

member states in the so-called Group of Friends of Haiti. In

interpreting the popular sentiment, it is impossible to disagree

with these words by Liliane Pierre-Paul:

“The great majority of Haitians weren’t

mistaken and the promises ultimately did nothing to change the

disastrous perception of an international community that was

bureaucratic, condescending, wasteful, inefficient, and lacking

in soul, modesty and creativity.” [4]

As long as this model is not significantly

revamped there will be no solution. Social vulnerability and the

precariousness of the state continue to be major Haitian

characteristics. With the model applied by the international

community through the UN system, the TNGOs and the United

States, we are deceiving ourselves, misleading world public

opinion and frustrating the Haitian people.

Q: What are your thoughts

on the amount of agricultural land taken out of production to

make way for the Caracol Industrial Park, a $300 million

public-private partnership among a diverse set of stakeholders??

RS: Caracol symbolizes a development

policy far more than any loss of mainly agricultural lands. It

so happens that the Caracol model was used during the

dictatorship of Jean-Claude Duvalier and its results are known

to everyone. As a complement to agricultural production, Caracol

is acceptable. Nonetheless, to want to turn Haiti into a “Taiwan

of the Caribbean” [5] is to completely disregard the social,

anthropological, historical and economic characteristics of the

country.

Q: You write that

Venezuela’s PetroCaribe initiative was a key motive for the U.S.

government’s turn against Préval. Why then do you think the U.S.

and the OAS wanted a candidate – Michel Martelly – in the second

round of elections who would ultimately be even friendlier with

Venezuela? Do you think Martelly’s relations with Venezuela

might pose a threat to him as well?

RS: Compared to the alleged

development cooperation model imposed by the international

community on Haiti, Cuba and Venezuela follow absolutely

opposite paths. Whatever our opinion about the domestic policies

of these countries, it cannot be denied that their form of

cooperation takes into account more the demands and needs

expressed by Haitians themselves. Cuba — lacking financial

resources and rich in human resources –since 1998 has

implemented a local family health and medicine program that

reaches the most remote places in Haiti. Cuban medical diplomacy

directly benefits the most humble of the Haitian people and

attempts to compensate for the brain drain in the health sector

promoted by certain western countries, particularly Canada.

In turn, although recent, the Venezuelan

development cooperation offered to Haiti asserts itself as a new

paradigm in the Caribbean Basin. It is sustained through the

following trilogy: on the one hand, Caracas listens to the

Haitian claims and strives to make its offers and possibilities

compatible with these demands. On the other, nothing is carried

out without the knowledge and previous consent of the public

institutions and the Haitian government. Finally, the

cooperation aims to bring direct benefits to the Haitian people

without taking into consideration any ideological discrepancy

there may be with the incumbent government in Haiti. This is a

principle equally espoused by Cuba and it explains not only the

absence of any interference by the two countries during the

election crisis of 2010, but also the excellent relations

maintained, both by Havana and Caracas, with the Martelly

administration.

The PetroCaribe program is the crown jewel

of Haitian-Venezuelan cooperation. Everything is put into it.

Everything depends on it. In the face of a true boycott of

Haitian public power promoted by the so-called Group of Friends

of Haiti, the resources made available by the PetroCaribe

program represented, in 2013, 94% of the investment capacity of

the Haitian state. [6]

Most of the beneficiary countries — as with

Haiti — do not include the resources from the PetroCaribe

program in the national budget, preventing legal and accounting

oversight. This situation generates distrust and criticism, both

domestic and foreign, due to the lack of transparency in using

them.

Far beyond its results, the philosophy on

which the Venezuelan cooperation is based contrasts with that of

the developed countries. The energetic Pedro Antonio Canino

Gonzalez, Venezuelan ambassador in Port-au-Prince since 2007,

highlights the principles that guide the actions of the ALBA

countries in Haiti: “We did not come to carry out an electoral

campaign in Haiti. Why would we make spurious commitments?

Venezuela’s assistance aims to attenuate the Haitian people’s

misery without any strings attached. My government isn’t even

interested in the Haitian Republic’s diplomatic relations with

other countries, including the U.S.. This is a prerogative of

the Haitian authorities, who are free to have relations with

whomever they wish.” [7]

This is the exact opposite of the long and

constantly increasing list of conditionalities that

characterizes the cooperation offered by the west. With

disregard for national idiosyncrasies, the idea of democracy is

used as a screen to camouflage their own national interests.

The United States and its allies in Haiti

should pay attention to the lessons of the young Venezuelan

cooperation because, in addition to respect for the public

institutions of the host state, as a current Haitian leader

bluntly states, ” Friendship with a country as poor and with as

many needs as Haiti isn’t measured in the number of years of

domination, but in how many millions are on the table. “[8]

Although the PetroCaribe program is based

on an anti-imperialist and liberationist discourse to mark a

break between Monroe and Bolivar, it is, in fact, a counter

model to traditional development aid from the developed

countries and international organizations. In the universe of

the international cooperation provided to Haiti, Venezuela

constitutes an exception, being the only one that provides,

regularly, financial resources directly to the Haitian state.

[9]

(To be continued)

* This article was originally published

under the title “International Crossroads and Failures in Haiti”

by the LA Progressive. Georgianne Nienaber is a freelance

writer and author and frequent contributor to LA Progressive.

Dan Beeton is International Communications Director at the

Center for Economic and Policy Research and a frequent

contributor to its "Haiti: Relief and Reconstruction Watch"

blog.

Notes

1. ABC News, March 9, 2012. Accessed

January 7, 2014.

2. Seitenfus: “I prefer the term TNGO

because I am only referring to the foreign non-governmental

organizations that operate in Haiti.”

3. In Le Nouvelliste, Michaelle

Jean: Présidente d’Haïti ? , Port-au-Prince, March 25, 2013.

4. La grande manip in Pierre Buteau, Rodney

Saint-Eloi and Lyonel Trouillot, Refonder Haïti ?, Mémoire

d’encrier, Montréal, 2010, p. 290.

5. Duvalier — and backers such as the

Reagan administration – famously promised to transform Haiti

into the “Taiwan of the Caribbean” through low-wage apparel

production in the 1980s.

6. In Le Nouvelliste, June 28,

2013.

7. In Le Nouvelliste, March 11,

2013.

8. In Le Nouvelliste, March 5, 2013.

9. Seitenfus: “Taiwan’s cooperation to Haiti occupies a special

place. Devoid of bureaucratic obstacles, it is quick and is

preferably used with the turnkey (clef en mains) model.”

|