|

Karl Marx

once famously remarked that history repeats itself “the

first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

This maxim comes to mind when examining the class

dynamics surrounding the final days of President Michel

Martelly’s regime in Haiti today. They are similar to

those of 30 years ago, when the dictatorship of

Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier was unraveling.

To compare the Haiti of 1986 to that of 2016, one

must understand the nation’s underlying class make-up.

A Quick History

After Haiti’s birth in 1804, two

ruling classes emerged. The first was a comprador

bourgeoisie, whose capital was invested and reproduced

in the importation of foreign manufactured goods and the

export of Haiti’s agricultural products, chiefly sugar,

coffee, and cacao. The other ruling group was the big

landowners, or grandons, who owned, leased, or controlled Haiti’s farmland. In a

semi-feudal arrangement, sharecroppers, known as

dè mwatye (two halves), tithed a large portion of their cash crops

to the grandons.

Haiti’s turbulent coup d’état-scarred history

reflects the struggle between these two rival ruling

groups for state power, and hence economic advantage.

In 1915, U.S. Marines began a two decade military

occupation until 1934, during which time they favored,

for both racist and economic reasons, the largely (but

far from completely) lighter-skinned comprador

bourgeoisie.

The reaction to the brutal, bloody, racist U.S.

regime was the emergence in 1946 of

grandon-leaning

President Dumarsais Estimé, whom Gen. Paul Magloire

ousted in a 1950 coup on behalf of Haiti’s bourgeoisie.

Magloire’s corrupt regime gave rise to the election in

1957 of Dr. François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, who had been

Estimé’s Health and Labor Minister and was a champion of

the grandons.

To resist the political pressure and

counter-attack of the bourgeoisie and Washington (which

tolerated but was not comfortable with his regime),

Duvalier formed an infamously repressive and arbitrary

paramilitary force known as the Volunteers for National

Security (VSN), or, informally, the Tonton Macoutes

(Uncle Sack). Duvalier’s vicious corps killed tens of

thousands of Haitians, often under the banner of

“fighting Communism” and its spread from neighboring

Cuba.

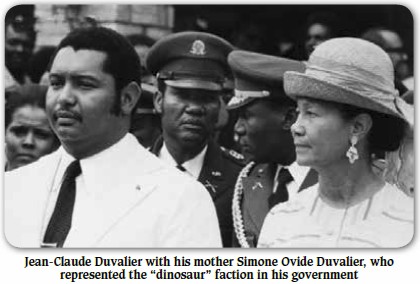

Papa Doc died in 1971, passing on his title of

“President for Life” to his son, Jean-Claude. But Baby

Doc had attended elite schools with the children of

Haiti’s bourgeoisie, so his regime became something of a

hybrid. Half of it was dominated by generals and

strongmen from Papa Doc’s clique, known as the

“dinosaurs,” while the other half was made up of

bourgeois “technocrats,” either friends from school or

reformers suggested by Washington. The “technocrats”

favored foreign investment and capitalist development,

which made more inroads into Haiti after Papa Doc’s

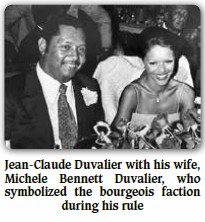

death. In 1980, Jean-Claude married a bourgeois

princess, Michele Bennett, whose father imported cars

and exported coffee.

Under Jean-Claude, Michele Bennett became the

symbol of the bourgeoisie’s influence, while his mother

and Papa Doc’s widow, Simone Ovide Duvalier, represented

the Macoute sector.

Repressive, corrupt, and bipolar, Baby Doc’s

regime finally fell in 1986 due to a popular uprising

but also a change in U.S. policy to begin replacing its

revolution-provoking tin-horn dictators with

“technocrats” and pro-neoliberal politicians elected

with Washington’s financial backing and political

support.

Neo-Duvalierism Returns with Martelly

Fast forward 25 years to 2011.

Washington illegally shoehorns into power President

Michel Martelly, overruling Haiti’s sovereign

Provisional Electoral Council (CEP) with pressure from

the Organization of American States (OAS) and then U.S.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

For 20 years, Haiti’s political scene had been

dominated by the alternating presidencies of former

liberation theologian priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide and

his erstwhile ally, enlightened bourgeois

agronomist/baker René Préval. Their governments had been

undermined, hobbled, and bowed by two U.S.-backed coups

d’état in 1991 and 2004, and two ensuing foreign

military occupations.

The mass movement which first brought Aristide to

power in a 1990 election had a democratic,

anti-Duvalierist, anti-imperialist agenda. Martelly’s

Washington-assisted rise was the return of a

neo-Duvalierist regime, with a “Macoute” wing and a

bourgeois wing, and in post-earthquake Haiti, it aimed

to snuff out the weakened but persevering popular

movement.

Over the previous three decades, Haiti’s

traditional semi-feudal agricultural-export economy had

been largely destroyed. Although still importing motor

vehicles, refrigerators, computers, and perfume, Haiti’s

comprador bourgeoisie had moved mostly into building,

owning, and managing assembly factories producing

electronics and clothing for the U.S. market.

The dè

mwatye peasant agriculture that once supported the

grandons had

largely been crushed by the neo-liberal dumping of

foreign products – particularly rice – from the U.S. and

the neighboring Dominican Republic. The changing

grandon class,

with its recent Macoute past, increasingly turned to

illicit trades like drug-trafficking, kidnapping, land

theft, and the black-market for its livelihood and

gravitated towards careers in the police and

Martelly-resurrected Haitian army, which had been

demobilized by Aristide in 1994.

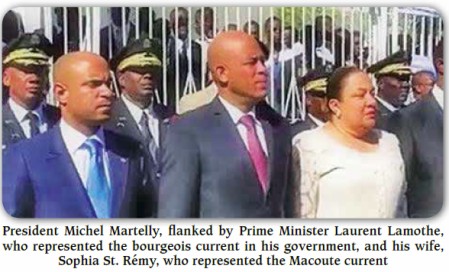

Representing the bourgeoisie under Martelly was

his Prime Minister and long-time business partner

Laurent Lamothe, who was trained in business at schools

in Florida and had become a rich, successful

telecommunications magnate.

Representing the Duvalierist wing were Martelly’s

wife, Sophia St. Rémy, whose father and brother were

drug traffickers, along with the children of many

prominent officials from the Duvalierist era like

Constantin Mayard-Paul, Claude Raymond, Mme. Max

Adolphe, and Adrien Raymond.

Even Baby Doc’s son, Nicolas, had a job in the

Martelly government, as did some of Jean-Claude’s former

ambassadors like Daniel Supplice and Dr. Pierre Pompée.

Also periodically part of Martelly’s government

was the flamboyant pundit Stanley Lucas, the scion of an

infamous peasant-massacring Jean Rabel

grandon

family, who, as an agent of Washington’s International

Republican Institute (IRI), had a prominent role in the

lead-up to the 2004 coup against President Aristide.

In its composition and program, the

Martelly/Lamothe government was a virtual photocopy of

Jean-Claude’s regime, using the same economic

cornerstones of tourism and sweatshops. It even

resurrected the same slogan that the Jean-Claudistes had

coined: “Haiti is open for business.”

But just like Baby Doc’s, Martelly’s regime was

marked by outrageous excess, infighting, dysfunction,

corruption, and repression, leading to a mass rebellion

which almost drove it from power in late 2014. To save

his presidency, Martelly sacrificed his Prime Minister,

Lamothe, who would have been the presumptive

presidential candidate of Martelly’s Haitian Bald-Headed

Party (PHTK) in 2015. (Constitutionally, Haitian

presidents are limited to two non-consecutive terms).

For his PHTK successor, Martelly turned to an

unknown provincial businessman, Jovenel “Neg Banann”

Moïse, who had developed, with a $6 million government

subsidy, a tax-free agro-industry “Agritrans,” exporting

bananas mainly to Europe.

With an export-oriented agribusiness built on the

dispossession of small peasants, Jovenel Moïse

represents what Haitians call the “Macouto-bourgeois”

alliance that characterized the regimes of Martelly and

Baby Doc.

Many also speculate that the state lands now

leased to Agritrans would eventually be turned over to

foreign mining interests to continue their now-stalled

exploration and environmentally-destructive mining for

gold in Haiti’s northern mountains.

The children of Haiti’s comprador bourgeoisie and

grandons, as well as other privileged petit-bourgeois strata,

usually go to school and college overseas in Europe, the

U.S., or Canada. There, they often become doctors,

lawyers, engineers, or some other professionals, taking

their place in Haiti’s

classe moyenne, or middle class.

With the degeneration of the Haitian economy,

scores of the classe moyenne have flocked to politics to get a piece of the state,

which has become Haiti’s most viable “industry” in

recent years.

The Struggle Ahead

Through the electoral fraud he

engineered in the Oct. 25 first round of Haiti’s

presidential race, Martelly sought to install Jovenel,

who was to go to a second-round with a leading 33% of

the vote (although a Brazilian exit poll suggests he

placed fourth with just 6% of the vote). That second

round, last scheduled for Jan. 24 after two

postponements, was suspended indefinitely on Jan. 22,

and five of the nine CEP members, including

President Opont Pierre-Louis, have resigned.

Although there were 54 presidential candidates,

there are only three heavyweights in the opposition to

Jovenel and Martelly, and two of them are “Lavalas.”

The first Lavalas candidate is Dr. Maryse

Narcisse of former Pres. Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s

Lavalas Family party (FL), who supposedly placed fourth

with 7% of the vote. Then there is the breakaway

Dessalines Children platform (PD) of former Sen. Moïse

Jean-Charles, who supposedly placed third with 14% of

the vote.

The third heavyweight is supposed second-place

finisher (with 25%) Jude Célestin of the Alternative

League for Haitian Progress and Empowerment (LAPEH),

which is affiliated (albeit informally) with Préval’s

platforms Vérité and Inite, under whose banner Célestin

ran in 2010.

Both Washington and Martelly wanted to

marginalize the two Lavalas currents and keep them out

of any run-off. Although their leaderships adopt

moderate positions, their popular bases remain very

mobilized and dangerously radical.

Therefore, Washington favors a monolithic

two-party system in Haiti (like that in the U.S.), which

would establish an alternance between “acceptable”

players, parameters of debate, and political programs.

The Republican analogue would be the PHTK, while the

Democratic surrogate would come from the current Préval

constellation: LAPEH, Vérité, or Inite.

Not surprisingly, Lamothe, singer Wyclef Jean,

and large sectors of Haiti’s ruling elite have thrown

their support behind Célestin, who could be expected to

give the U.S. the same grudging but faithful

collaboration that Préval did.

Célestin and seven of the other leading

presidential runners-up (except the FL) are in a “Group

of Eight” (G8), whose unity is more formal than real.

While the masses in giant demonstrations demand the

elections’ annulment and Martelly’s arrest, the G8 and

FL do not. They insist instead on an “independent

evaluation commission” to review the Oct. 25 results,

each of the heavyweight candidates asserting that they

won the election in the first round. Whatever results

any evaluation commission finds, it will surely explode

the opposition’s tenuous unity.

Meanwhile, the masses continue to vent their

anger and frustration at Martelly and the dismal

elections he has finally delivered after four years of

delay.

Senate and National Assembly President Jocelerme

Privert has proposed a complicated transition predicated

on the Martelly’s Feb. 7 departure and the new

Parliament staying, although many new lawmakers’

elections are also hotly contested. The G8 proposes a

transition where fraudulently elected lawmakers would be

selectively “ejected.”

The missing element in this revolutionary

cocktail, at the present moment, is a vanguard,

revolutionary party or front to lead and champion the

masses’ increasingly radical demands. Currents like the

Dessalines Coordination (KOD), the Democratic Popular

Movement (MODEP), and others have been talking but have

not yet forged an operational unity.

However, if history is any guide, Haiti’s

political crisis and revolutionary potential promises to

continue for several months at least. The window after

Baby Doc’s fall in 1986 lasted for four years, until the

popular movement carried out a political revolution on

Dec. 16, 1990 with Aristide’s first election.

Many veterans and students of the struggles of

the 1980s and 1990s now realize that a deeper social

revolution – changing Haiti’s property relations, above

all concerning land – is necessary for any progressive

or revolutionary government to survive.

Furthermore, the ruling class is either divided

on or unsure of how to go forward and maintain power,

offering a unique opportunity for Haiti’s uprising.

All these factors offer hope that the anti-imperialist

movement among peasants, workers, and the urban

unemployed that began with Duvalier’s ouster 30 years

ago can finally make some headway after its many

setbacks.

|