|

This report is

based on extensive interviews,

on-site and via phone,

with more than 20 government officials, economic

development professionals, peasant farmers, and

community organizers, between July 2015 and January

2016. We reached out to Agritrans for comment, but they

did not respond.

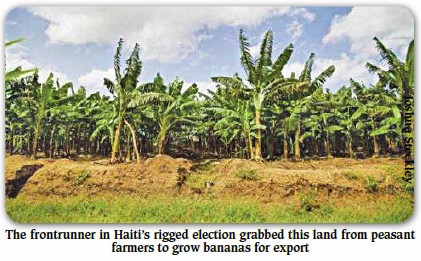

The only

man who was running in Haiti’s now-postponed

presidential election run-offs

on Jan. 24, 2016, Jovenel Moïse, dispossessed as many as

800 peasants – who were legally farming –

and destroyed houses and crops two years ago, say

leaders of farmers’ associations in the Trou-du-Nord

area. Farmers remain homeless and out of work. The land

grabbed by the

company

Moïse founded, Agritrans, now hosts a

private banana plantation.

To grow bananas for export in a hungry nation,

Agritrans received

at

least $6 million in state loans, and

possibly much more. Agritrans seized a 1,000-hectare

(2,371-acre) tract from farmers, bulldozed their houses

and fields, used bribes to buy local support, distorted

claims of its benefit to local residents, and created a

phantom organization to legitimate itself.

Should he become president, the company Moïse

created would likely be a bellwether of loss of family

livelihood and domestic food production.

To stand for office, Moïse stepped down from

Agritrans last year, though he is still campaigning

under the moniker

Nèg Bannann, or the Banana Man. He portrays himself

as an

entrepreneur

determined to transform Haiti’s

agricultural sector into private enterprise.

Moïse would have appeared alone on the

presidential ballot after the only other candidate who

was imposed on the run-off slate said that he would not

participate in

“this

farce… [of] selections.” Moïse is from

the political party of the current president Michel

Martelly, whose principal platform has been “Haiti: Open

for Business.” Martelly himself came into office in 2011

through an invalid election backed – like the current

one – by then U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton,

who played a

pivotal

role in imposing him.

A Moïse presidency would ensure that political

decisions prioritize free trade and private enterprise

over support for the destitute majority. This, in turn,

would likely give a green light to massive land grabs

that are planned or in process, while peasants working

the land would be dispossessed.

Expropriation and

Destruction of Homes

In August

2013, according to local residents, Agritrans forcefully

expelled hundreds of farmers who were legally using the

land. Local leader Milosten Castin, coordinator of the

organization Action to Reforest and Defend the

Environment, said that, with no warning, several

bulldozers invaded the land, plowing under crops and

forage used for grazing. The machines later destroyed

the homes of at least 17 families, many of whom remain

homeless today.

After protests organized by the Peasant Movement

for the Development of Deveren (MPDD) took place,

Agritrans gave the owners of the destroyed homes US$40

to US$700 each in compensation. Gilles St. Pierre, a

member of MPDD who lost his concrete block house, said

the compensation was inadequate. “What am I supposed to

do with $700 ?,” he asked in a phone interview. “I had a

house and land… and now I work as a taxi driver.”

Food for Export, Not for

Eating

The

Agritrans plantation is the first

agricultural

free trade zone in the country,

established by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

This allows the company to take advantage of perks of

reduced tax and tariff payments, along with special

customs treatment.

By Haitian law, free trade zones must export at

least 70% of their products. Currently, Agritrans’

production – an estimated 40 containers of bananas

weekly – is shipped to Germany. At the same time, Haiti

does not produce enough food to feed itself. Destitute

Haitians must rely on imported staples, whose

costs

are expected to rise this year.

The irony of shipping food to Europe was not lost

on one woman whose land had been seized. Asking to

remain anonymous for fear of retribution, she said,

“They’re sending bananas overseas, and now we have to go

to the border to buy Dominican bananas and plantains… It

doesn’t make sense.”

Another land grab may be imminent. In order to

comply with the contract with its German client, within

the next three years Agritrans must ramp up production

in order to ship 150 containers, equalling

160,000

tons, to Germany

each week. According the current CEO of Agritrans,

Pierre-Richard Joseph, this increase will require

3,000

more hectares of land.

One of the main demands of peasant groups in the

region, like their counterparts around Haiti, is food

sovereignty, whereby people democratically control the

production of food to meet the needs of their country

through local, ecological, and small-scale agriculture.

Another demand is government support for family

farming, including access to land, water, and markets.

“Haitian agriculture is based on peasant farms,”

said Castin. The World Bank estimates that

80%

of Haiti’s rural population

is engaged in small-scale agriculture. “Any plan must

support their mode of [growing],” he said. “That’s what

will change this country.”

Arid Land for Family Farming,

Irrigated Land for Commerce

Moïse

described the land in question as “abandoned,”

and also stated that Haiti has over one million hectares

of land “that

is being used for nothing.” Local peasant

groups disagree.

They argue that prior to

Agritrans’ takeover of the 1,000 hectares, the semi-arid

land was actively used by peasants, despite the limited

resources available to them. Peasant organizations and

individual farmers were grazing cattle on it and selling

the milk to NGOs and small-scale milk and yogurt

processors. Other farmers grew crops like millet,

cassava, corn, beans, and sweet potatoes, both to feed

their families and sell on the local market.

Now that the land is held by Agritrans and

millions of dollars in state loans have been invested in

it, row upon row of lush banana trees grow there,

irrigated by pumping groundwater. The transformation

reveals a fundamentally political question: If the land

had the capacity to become so productive, why didn’t the

government support peasant farmers to make it so,

instead of providing massive support to private

interests?

A woman living near the banana plantation stated,

requesting anonymity, “The government builds roads,”

that go past her garden, so “they could easily build

water reservoirs and irrigation canals. But they don’t.”

Creating or Destroying

Employment?

Moïse has

cited the banana plantation in his campaign as evidence

of his ability to create much-needed jobs in a country

where

formal

employment is 13%. Agritrans says it will

create

3,000 desperately needed jobs once the

plantation reaches it full capacity, propelling the

local economy. As of March 2015, only

600

jobs had been

created, including for agronomists, engineers,

agricultural technicians, and farm laborers. However,

according to interviews with some of those laborers,

“jobs” on the seized land are defined as 15-day

shifts. This creates both precarious, short-term jobs

for families and misleading employments figures.

Workers are paid the minimum wage of 200 gourdes

(US$3.53) per day, plus a plate of food — an amount

which

Haitian

workers and other organizations, as well

as some prominent

factory

owners, say cannot support a household.

The minimum wage covers just

19-37% of the cost

of living in Haiti.

Moïse has claimed that

smallholding

farmers are included in the banana

business, both by providing labor as well as by holding

a 20% minority share in the business. He cited the

Peasant Federation of Pizans (FEPAP), claiming the

consortium was made up of eight peasant groups who had

previously worked the land.

According to leaders active around the plantation

area, this claim is misleading. In an interview,

Josaphat Antonéus, coordinator of a peasant coalition,

agreed. “FEPAP is a phantom organization,” he said.

“Peasant inclusion in the business is a facade

[Agritrans] wants to give at the global level.”

Castin claims that the so-called peasant groups

that make up FEPAP “were active back in 1980s. Maybe

they still have a president, or a secretary, but they

have no members today.” When asked about FEPAP’s 20%

shareholder status, Castin laughed. “Twenty percent of

what? No one in FEPAP is in Agritrans’ administration;

they don’t know what the profits are.”

Ben St. Jacques, an activist with a community

organization in the area, claimed that Agritrans paid

peasants to support the project, offering motorcycles

and televisions to FEPAP members.

According to residents, most of those who found

employment with Agritrans had never before had access to

the land. The organizations that allegedly comprise the

confederation of FEPAP had legal access to only

approximately 100 hectares prior to Agritrans’

take-over. Conversely, most of those who had worked the

land before being kicked off, and who had protested

their eviction, never found wage-work on the plantation.

For Gilles St. Pierre, who lost his home to the

plantation, while any single-candidate presidential

run-off is a farce, its outcome is deadly serious. “If

Jovenel is elected, he’ll have the same people around

him [who ordered my house razed], and he’ll do the same

thing again. It will be a disaster for small farmers,

even those with legal rights to the land.”

“If Jovenel becomes president,” he said, “this

country is finished.”

Beverly

Bell, coordinator of Other Worlds, is an organizer

and writer who has worked with social movements in Haiti

for 35 years.

Natalie Miller, Other Worlds’ Media and Education

Coordinator, also helped with this article.

An earlier version of this article was first published on Other Worlds’

website, and is the third piece in a series on

land

rights and food sovereignty in Haiti.

|